"Willful Defiance" Suspensions Persist Despite Years-Old Ban

The story was co-published with Sacramento Observer as part of the 2025 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California. This story is the second of a three-part series.

Jayshawn Yancey, front, almost didn’t finish school because of disciplinary practices that put him out of the classroom and into the streets. He now mentors other Black students struggling with mental health. Courtesy of Jayshawn Yancey

For Jayshawn Yancey, school was more than just a place to learn. It was an escape from a turbulent home life marked by abuse from foster parents. Yancey never knew his father and his mother died suddenly when he was just 4.

But the trauma he experienced at home began to surface in his behavior at school. As early as elementary school, he started getting into fights. Teachers and administrators quickly labeled him a problem student. He was regularly suspended or removed from class, often spending the rest of the period alone.

“I probably fought at every level,” recalls Yancey, now 26. He says the anger stemming from the abuse he endured at home was at the root of his behavior.

By the time he reached middle school, things had worsened. During a meeting with the principal, Yancey was told that the school wasn’t meant for students like him. He was immediately placed on a half-day schedule, denying Yancey a chance to attend regular class.

“He didn’t give me a fair chance to be a student,” Yancey says. “He judged me based on my track record from other schools.”

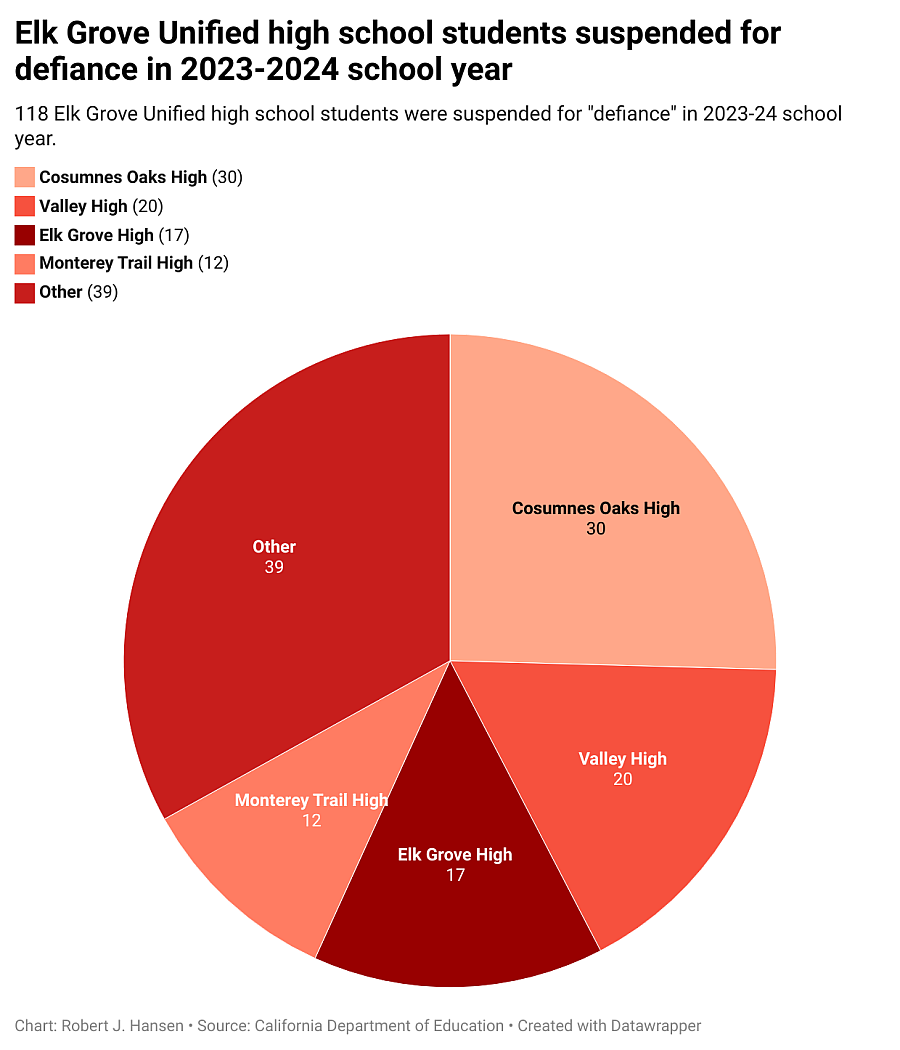

Although California has banned suspensions for “willful defiance” in grades K-12, both Elk Grove Unified and Sacramento City Unified school districts continued to suspend students for defiance during the 2023-24 school year, according to an OBSERVER analysis.

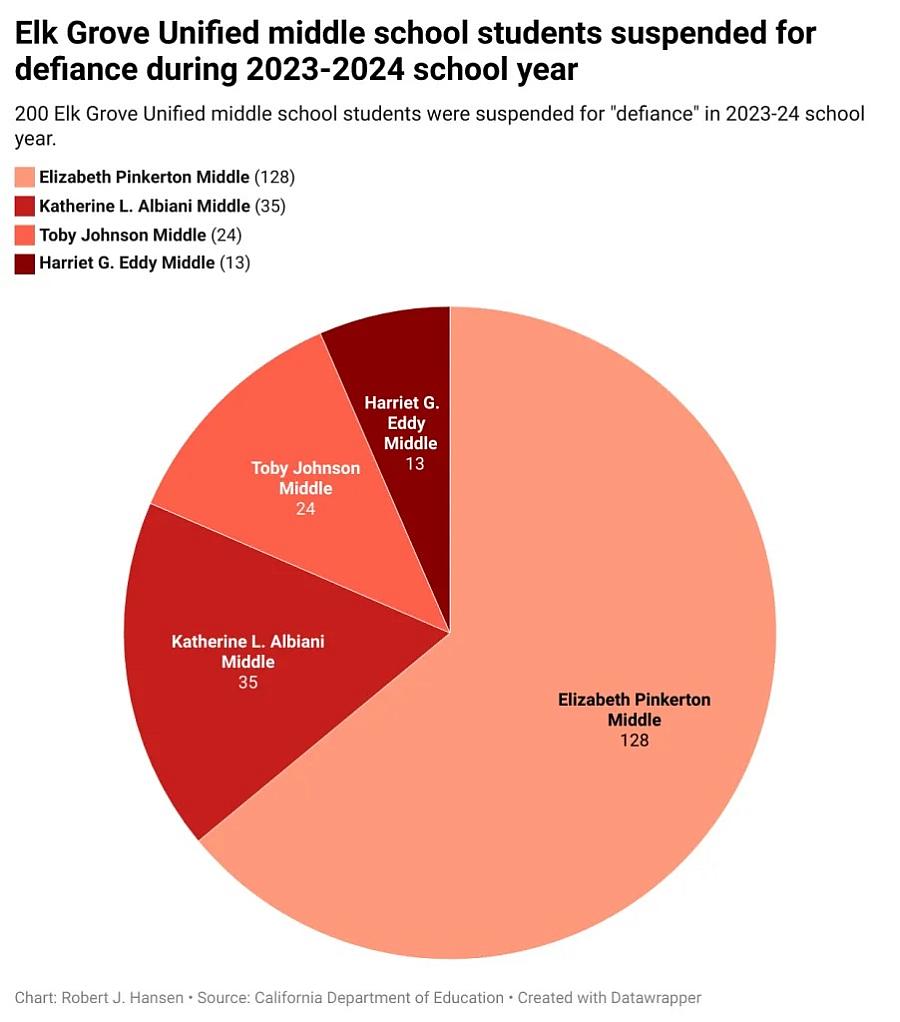

The data show that hundreds of students – many of them in middle school – were removed from school under a category the state no longer allows. The issue has gained new relevance as federal policies under the Trump administration threaten funding for schools that implement equity-based discipline practices.

Research has found that school suspensions can lead to higher rates of depression through adolescence and into early adulthood. Adolescents who were suspended or expelled showed “significantly higher depressive symptoms,” the researchers found. Another study found that students who were suspended or expelled reported poorer physical health from adolescence through middle age.

For Yancey, the cycle of suspensions continued. He fell further behind in school and spent more time unsupervised in his neighborhood.

“School was probably a better place for me to be than at home,” he says. “When they sent me home, I’d just end up in the streets. At least on campus I was being supervised.”

Yancey believes being excluded from school leaves students feeling rejected and abandoned. He was one of those kids who needed school the most, yet was pushed away.

“I wasn’t accepted,” Yancey says. “When teachers saw me, they saw bad behavior. But what they didn’t understand was that those behaviors came from unmet needs.”

Instead of support, he got punished.

“Then you go back to school and they expect you to know everything, or they expect you to take the initiative to try to catch up on what you missed.”

Yancey’s experience reflects a long-running crisis in school discipline at the state and national levels. Last year, California prohibited the suspension of students at all grade levels for minor offenses categorized as “willful defiance.”

Willful defiance is the act of a student intentionally disregarding school rules or directions, such as refusing to follow instructions, not bringing necessary materials, wearing prohibited clothing, or displaying behavior perceived as disrespectful toward school staff.

It has been broadly used to justify suspensions and expulsions for a wide range of behaviors – from minor infractions such as talking back to teachers to more disruptive conduct – and has been disproportionately applied to students of color, those with learning disabilities, and students from low-income backgrounds.

Yancey doesn’t know whether he was suspended for willful defiance but says he got in trouble so often that he probably was.

California has taken steps to address disparities in student discipline for more than a decade. In 2013, California banned willful defiance suspensions for students in grades K-3. In 2019, the state extended the ban to fourth and fifth grades permanently, and grades 6-8 for five years. Most recently, in 2023, California expanded the permanent ban to include grades 6-12, effectively eliminating willful defiance suspensions statewide for all K-12 students.

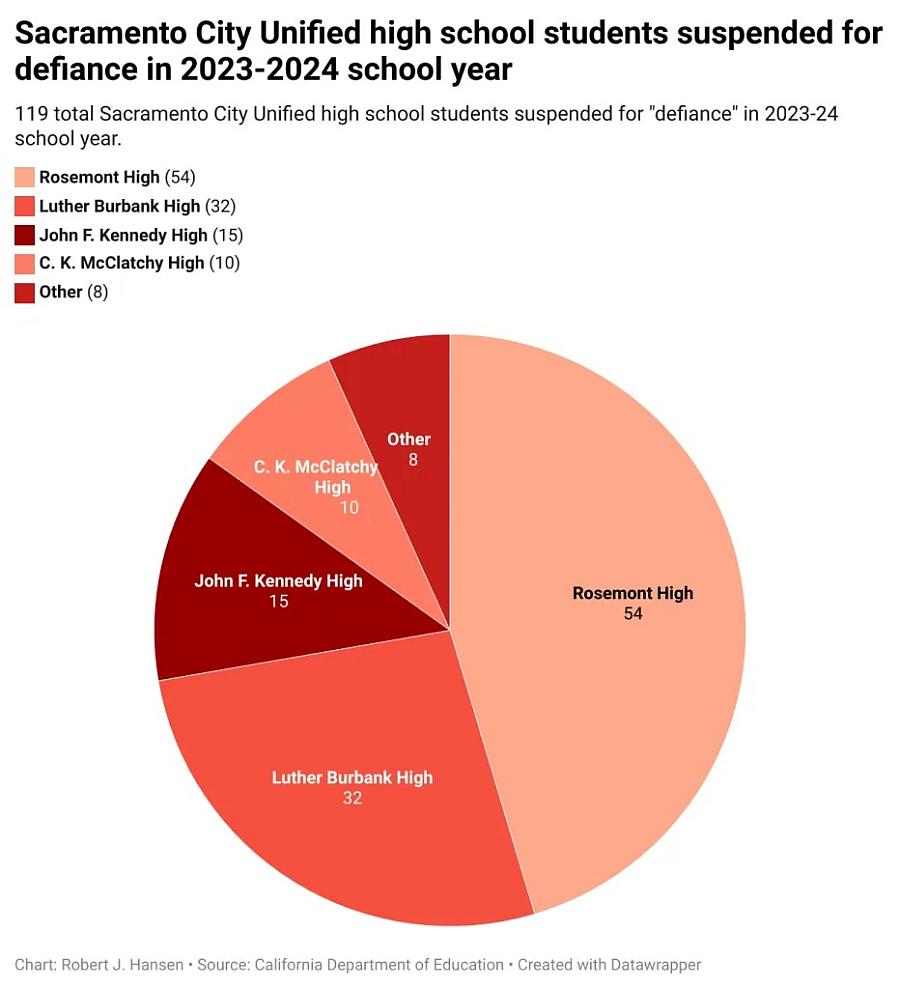

An OBSERVER analysis found that during the 2023-2024 school year, Sac City Unified suspended 119 high school students for “defiance” at eight of the district’s high schools. Two high schools, West Campus and Hiram Johnson, had zero suspensions for defiance.

Elk Grove Unified suspended 324 students for defiance, 200 of whom were middle school students. Six elementary school students were suspended for defiance well after the state banned its use as reason for suspension.

Notably that same school year, Sac City Unified suspended no middle or elementary school students for willful defiance.

Available data do not include racial demographics for student suspensions for defiance. However, Elk Grove Unified and Sacramento City Unified School Districts still have some of the highest suspension rates for Black students in California.

Elk Grove Unified told The OBSERVER in an email that although California law bans out-of-school suspensions for willful defiance in elementary and middle school, teachers remain legally allowed to suspend students from their classroom for up to two days for behaviors such as defiance.

Roger Dickinson, former assemblymember and author of the original bill limiting the use of willful defiance in 2013, told The OBSERVER the purpose of the legislation was to limit the use of willful defiance because it historically had been disproportionately applied to students of color, foster youth, low-income students and students who identified as LGBTQ.

“This ‘willful defiance’ was obviously a catch-all for things that hadn’t been specifically identified but the number of things that were specifically identified pretty much covered the waterfront of the kind of serious behaviors,” said Dickinson, who now is on the Sacramento City Council. He added that the 2019 expansion of his bill limited the justification for using willful defiance as basis for suspension and that districts’ continued use of such justifies further examination.

Research shows the category of “willful defiance” was disproportionately applied to at-risk students – including Black and brown students, foster youth, homeless students, those with disabilities, and LGBTQIA+ students.

The 2024 law banning suspensions for willful defiance, sponsored by State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tony Thurmond, was designed to tackle the root causes of student disengagement, especially among marginalized youth.

The law aims to reduce lost instruction time by no longer suspending students for minor misbehavior, which can lead to them falling behind academically or even dropping out.

Research suggests that being suspended even once in ninth grade doubles the risk of dropping out of school, according to a 2014 Johns Hopkins University study.

At the federal level, school discipline policies have swung back and forth between administrations. In 2014, the Obama administration issued guidance aimed at addressing racial disparities in school suspensions and expulsions. That guidance emphasized alternatives to exclusionary discipline, such as restorative justice programs like those used at Davidson Middle School in San Rafael, where peer juries resolve student conflicts without suspensions. After implementing the program, the school reduced suspensions from more than 300 to just 27 in a single year, according to Education Week.

The first Trump administration rolled back the policy in 2018, arguing that it led to inconsistent discipline across racial groups and claiming some students who should have been removed from classrooms remained due to concerns about equity.

In 2023, the Biden administration reinstated the Obama-era approach, reaffirming a commitment to addressing the disproportionate punishment of Black and brown students.

Jayshawn Yancey, second from right, displays his clothing line with the help of students he mentors at the RAGE project. Courtesy of Jayshawn Yancey

Jayshawn Yancey, second from right, displays his clothing line with the help of students he mentors at the RAGE project. Courtesy of Jayshawn Yancey

In April, the Trump administration issued an executive order requiring a detailed report on school discipline practices associated with diversity, equity, and inclusion.

The order directed federal agencies to assess whether public funds were supporting what it called “racially preferential policies,” including through nonprofits. It also called for the development of model discipline policies aligned with what the administration described as “American values.”

In response to this federal focus, the California Department of Education issued a letter to local districts reinforcing the legality and importance of addressing discipline disparities.

The letter also countered claims from the Trump administration that restorative justice and equity-based practices have made classrooms less safe – a claim not supported by data, the state says.

“Disproportionate discipline of students based on race is a real concern in our education system that should not be ignored or obfuscated by the Trump Administration,” the letter states. “The California Department of Education is proud of the progress our state has made to address school safety while reducing out-of-school suspensions and addressing discriminatory disparities in suspension rates.”

Yancey credits his high school counselor, Jody Johnson, with changing his life’s trajectory.

“He didn’t judge me – he just showed up,” Yancey says. “He was the first person to really advocate for me.”

Growing up in foster care, Yancey lacked consistent adult support. When teachers or administrators called home, he says relatives often believed the worst. But with Johnson, he had someone who listened, believed him, and stepped in when needed.

“Jody kept me from getting in more trouble. He made me feel seen and gave me a safe space – even food when I needed it,” Yancey says. “He had a way of making Black students feel like we belonged.”

Johnson also introduced Yancey to the idea of college. “I didn’t think college was for me until I visited one,” he says. “I didn’t even consider Sac State until I saw an HBCU. It opened my eyes.”

Yancey finished high school and later attended Sac State, but wasn’t able to finish because balancing work and school became too difficult. He became homeless at one point.

Today, Yancey is a youth engagement consultant for the RAGE Project, a nonprofit dedicated to advancing the well-being of youth of color ages 13-26 by providing trauma-informed coaching, community-based leadership development, and strategies to heal from the impacts of racism and systemic oppression.

He says his role gives him a purpose he never thought he would find. Yancey consults on youth projects and engages with youth at local schools, teaching them that, if they need, RAGE project provides a safe space.

“I’m like the bridge between the community and the youth,” Yancey says.

It’s a role he never imagined for himself, but one he hopes can keep other kids from falling through the same cracks he once did.

This project was supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, and is part of “Healing California”, a yearlong reporting Ethnic Media Collaborative venture with print, online and broadcast outlets across California.