Trauma, cultural barriers make sex education difficult for Asian Americans

This article was produced as a project for the California Health Journalism Fellowship, a program of the Center for Health Journalism at the USC Annenberg School of Journalism.

Other stories in the series include:

A hard silence to break: LGBT Vietnamese struggle for understanding

My mother did not say much when I got my first period at the age of 14.

Up until that point, I had learned about menstruation in my fifth grade class and had read the human reproduction chapter of my biology textbook several dozen times. I had seen plenty of sex scenes in movies, and a few terrifying pornography clips on the Internet.

But none of that prepared me for my first period. I came home from school that day and was startled when I sat on the toilet and saw a dark greasy stain on my underwear. I hid in the bathroom for some time before I realized what had happened, and went to tell my mom.

She was busy in the kitchen, in those hasty hours between picking up the kids from school and dinner at six, and walked over to the bathroom and showed me the cabinet where she kept the sanitary pads.

"Okay," she said. "Don't forget to do the laundry."

That was all my mom said to me from that day forward about menstruation or my sexual health, aside from reminders to clean the blood stains on the sheets, or scoldings if I left my bras or sanitary pads out where they could be seen by my older brother.

And it was not until years later, at age 23, that I finally talked to her openly about sex, in order to interview her for this article.

It's a common experience among many Asian American families: skillfully avoiding the topic of sex until absolutely necessary, which is often too late.

Annie Yang, 23, recalled her first official 'sex talk' sparked by a permission slip sent home before the start of the sexual health unit of her ninth grade health class.

Annie's parents, who are both Chinese American, struggled to cobble together a philosophy on the spot.

"They were like, 'this is a thing that happens, when a man loves a woman. And just don't do it. And be careful when you do do it,'" Annie said. "And then we all went and watched Jeopardy. It was really awkward."

It wasn't until years later -- after Annie's first year of college, when the subject came up again.

"We had a talk about it after I told them I was sexually assaulted freshman year. I didn't feel comfortable telling them at all - it just wasn't a subject we had ever broached before," she said. "It burst out because my grades were dropping...and so I finally told them that way."

"I just remember feeling very blamed," Annie said. "Like, why would you even hang out with a boy, why would you even be there when it was so late, it's your responsibility, we sent you to this really good school."

While the generational and cultural disconnect on the subject of sex is certainly more pronounced in immigrant families, it is an issue that transcends race and ethnicity in this country.

In a recent study of 600 young people aged 12 to 15, nearly a third said they had never talked to their parents about sex.

Only 23 states mandate that sex education be covered, and of those, just 18 include information about contraception. Far more states, 37, cover abstinence, according to analysis by the New York-based Guttmacher Institute.

It was not until this year that sex education for students in grades 7 through 12 became mandatory in California, starting January of this year after Gov. Jerry Brown signed AB 329 into law.

Although teen pregnancy is now at an all-time low, the United States still has the highest teen pregnancy rate among developed countries.

The 'Sex Talk' Still Matters

While the modern teenager has access to a litany of sex education materials through books and the internet, the "sex talk" still matters, said Jenny Tang, a licensed clinical social worker and private practice sex therapist.

"A lot of my clients have already done their research and have a thousand ideas, but they don’t know what to do with them, and they're adults," Tang said, whose clients are mostly Vietnamese American adults.

Three decades of public health research has shown that when young people receive education they're more likely to wait until they are older to have sex; and when they do have sex they're more likely to use protection than those who receive no sex education or learn only about abstinence.

Teens who receive clear messages about sex from their parents are more likely to use condoms and birth control. This is especially true when it comes to young women who learn from their mothers about safe sex.

One survey of Asian American college-aged women found that parents were the least reported source of sex education, with the majority of women reporting school as their source of sex education.

A consequence of that is that Asian Americans are the least likely to use protection, with 40 percent of Asian American women having unprotected sex in their lifetime, according to a 2005 study. Another study found that 44 percent of college-aged Chinese and Filipino women used withdrawal as a contraceptive method, compared to the national average of 12 percent.

Nationally, Asian American women have the second highest percentage of pregnancies that end in abortion, at 35 percent. Vietnam has among the highest rates of abortion in the world, with 40 percent of all pregnancies ending in abortion.

Broadly speaking, it's hard for Asian American parents to talk about sex. Asian cultures tend to value deference, restraint and saving face. There are some things that are simply kept private, and sex is one of those things.

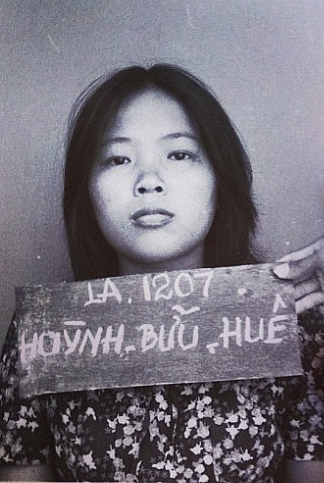

An intake photo of the author's mother, Hue, at a refugee camp in Malaysia.

My mother, Hue, reflects many Vietnamese-American immigrants, particularly those who grew up poor. With no more than a high school education and little to no sexual health education herself, she could not anticipate what raising four American children would entail.

Hue's father died when she was nine years old, leaving her mother -- illiterate and uneducated -- to care for twelve children on her own. My grandmother ran her own business in Saigon, selling hardware and building materials, and had little time to care for her children.

In a family so large and poor, the older children would care for their younger siblings, and there was not much time to think about things like puberty or sex, Hue said.

"My mother had twelve children, I think because she didn't know anything about birth control. Every year, one kid," Hue said in Vietnamese. "I went to school until the tenth grade, but nobody every talked about those things. No one wants to talk about it, it makes people uncomfortable."

Hue said it wasn't until she was 29 -- married, in the United States and thinking about having children -- that she took the time to educate herself about sex and reproduction.

"[Before that], I would listen to other people say things here and there. But I didn't really pay attention," Hue said. "I was just scared, and cautious -- okay, don't be so close to male friends or boyfriends. Keep a distance."

A Difficult Family Dynamic

How to address the subject of puberty and sex was a point of tension between Hue and my father Nam, who believed that talking about sex would plant ideas in our heads, and encourage more sexual behavior.

"I knew that it was something you should talk to your kids about," Hue told me. "But when I brought it up with your dad, he said, 'bà nói chi? Bà xúi nó chi?' 'Why talk about it - why are you encouraging them?"

"I told him, 'no, don't you think they know more than we ever did?'" Hue said.

But my father --whose dominating and sometimes abusive presence ruled our family dynamic -- won that argument, and for the most part forbid my mother from talking about puberty or sex.

His restrictive parenting style and explosive anger not only silenced my mother, but fostered distrust among his children.

My sister Vy, now 25 and a doctoral candidate at UC San Diego, had a difficult relationship with both of our parents growing up. She began dating her current partner when she was 16, an intense relationship that my parents feared, resisted and refused to accept for several years. Our brother, meanwhile, was able to have relationship without much controversy.

"I know that’s very unusual even for an American teenager. But I often felt that not only could I not tell them, they always were constantly telling me that my feelings were not legitimate," Vy said.

Unsure what was normal growth for a teenager, Hue was also constantly preoccupied with our physical development and weight, and made persistent comments about our eating habits and clothing sizes.

"She would tell me, as I was going through puberty and you develop fat deposits all over your body, 'I just don't want you to get a little overweight like your sister did,'" Vy said. "So it made me afraid to go through puberty, and really anxious about all the changes that were happening, because I didn't think what was changing was right."

Years later, Hue admits that her and my father's fears about their daughters were driven in part by what sex meant to her generation and the women before her -- pregnancy and ultimately, a loss of opportunity.

It's hard for her to envision the kinds of opportunities available to her daughters that she would never have.

"Sometimes I think, how was I so ignorant then? Over here [in the U.S.], these kids know everything, how did I know so little?" Hue said.

Shared Trauma

Although she has never been knowledgeable about sex, Hue has had plenty of experience with sexual harassment and assault.

It was common to go into movie theaters in Saigon and be groped, or have a man rub up against you at a parade. Anywhere where it would be crowded, she said.

When she was 14 or 15, she recalls a rare instance when her mother allowed her to go swimming with friends early in the morning. A man followed her as she rode her bike around the river, and flashed his genitals at her.

"I don't think I every really talked about that - nobody asked," Hue said. "I think there must have been others like me, but you just hold it inside you."

Growing up, our mother constantly repeated lines like "be careful" and "protect yourself," although she would never explain what that meant. Her fears and anxieties were often at the forefront of her parenting.

It was only after Vy told her that she had been sexually assaulted her senior year of college, that Hue told her about her experiences.

"I remember begin really afraid to tell her because...I had this idea in my mind that her talk was going to be like, 'be more careful, it’s your fault!' Because that’s the other undertone to 'be careful,'” Vy said. "That it's your fault if something happens. But she wasn't, she completely understood that it was very painful, that it was confusing, that it makes you feel powerless -- and that just being a woman implicitly puts you in this position of danger."

Hue told her a story about a driving instructor she had in Germany who took advantage of the time they were alone in the car to sexually assault her.

"She realized that, you can't just trust people. You can't even just be alone with another human and have that be okay," Vy said. "And that really resonated with me."

Tang says such parenting techniques aren't uncommon in the Vietnamese American community.

A mixture of traumas from their immigration experience and cultural parenting practices cause many parents to project their own fears and anxieties onto their children, and fall back on shouting or yelling when they can't gain control of a situation.

Parents often avoid addressing sex with their kids because they think talking about it will give their children more ideas.

"Those thoughts were already there, you just asked to see if they're there or not, and to what degree it's healthy or not," she said.

Tang, who is Chinese, was born in South Vietnam and grew up in Santa Ana. She recalls how excited she was to get her first period after learning about menstruation at school.

"I was armed with all this knowledge at school, but when I got it, I freaked out, I thought I was dying for two days," Tang said. She finally told her mother, who was upset and made her feel ashamed.

Tang adds that it's not wrong for parents to be uncomfortable with talking about sex. Especially for parents who don't have the education to inform that discussion, she says it's important for parents to signal to their kids that, even if they can't talk about it themselves, they're willing to help them get their questions answered.

"Parents can say, 'that's an interesting discussion that you’ve shared with me, maybe during your next physical you can talk with your doctor, or go to Planned Parenthood,'" Tang said.

A Lack of Resources

While attitudes may be slowly changing, there remain few sex education resources available for Vietnamese-American families.

In Orange County, those looking for family planning advice, birth control or sexual education can make an appointment with their doctor or a local clinic, such as Nhan Hoa Clinic and Planned Parenthood in Westminster. But those groups don't do active outreach or public education workshops in the community.

Although Planned Parenthood in Westminster had one such sexual health program for five years, staff turnover forced the clinic to put their outreach in the Vietnamese community on hold, according to spokeswoman Nichole Ramirez.

Ramirez noted, however, that Planned Parenthood OC is also in the process of translating its website and resource guides, which are already in Spanish and English, into Vietnamese.

Tang notes the lack of adequately translated materials, such as books for parents to read to their children.

"There's not competent translation at all. Even though there are people who charge for that, the impact of the material doesn't get across," she said.

There are even fewer resources for survivors of rape and sexual abuse, said Tang, who is not aware of any support groups that are conducted in Vietnamese.

Although much of my relationship with my parents so far has been ruled by silence and avoidance, in recent years, the lines of communication have reopened.

Freed from the power struggle of parenting adolescents, Hue has been more open, even eager to talk about her past struggles, her conflicts with my father and even ask me about my own relationships.

"I don't want your life to be like mine," Hue said. "I want you to know more."

[This story was originally published by Voice of OC.]