For Tribes in frontier Nevada, domestic violence brings a messy web of legal jurisdiction issues

This project was originally published in Nevada Current with support from our 2023 Domestic Violence Impact Reporting Fund.

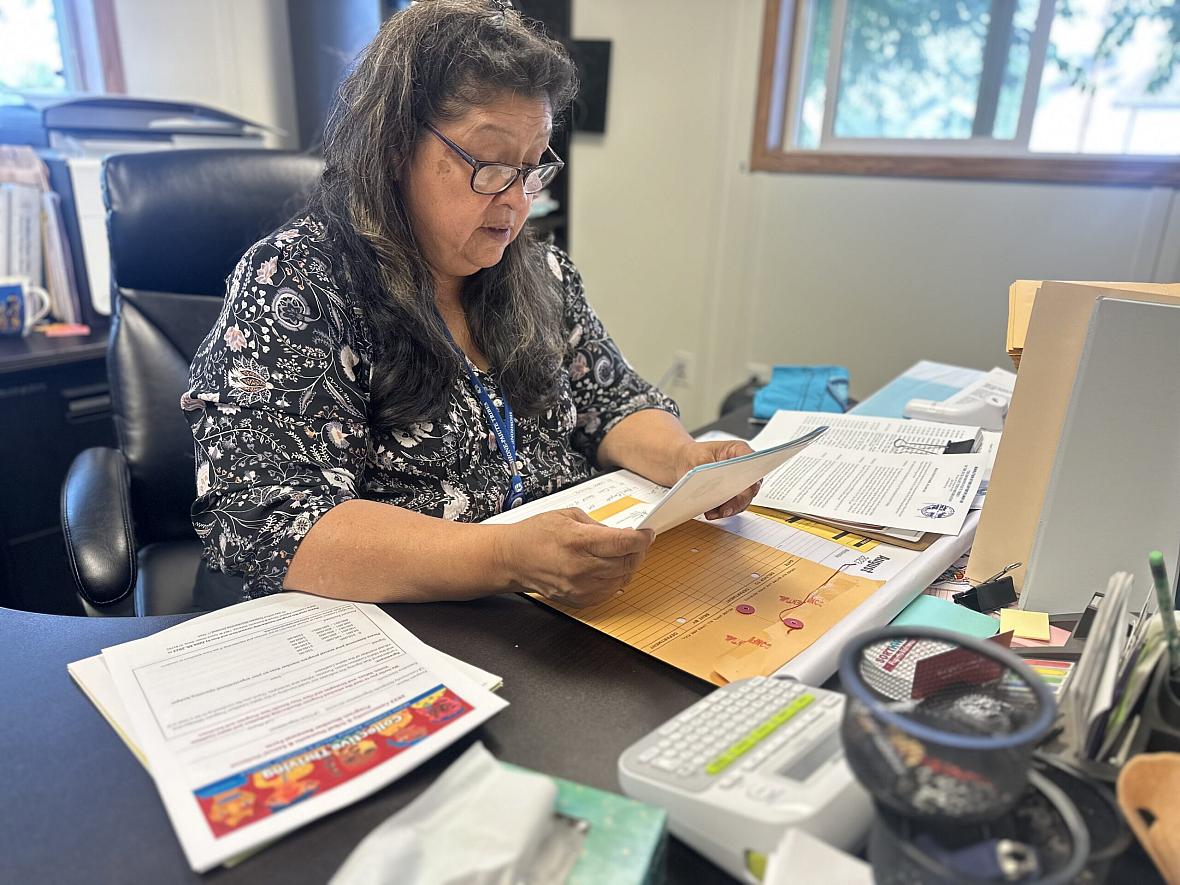

Kathy Gibson, who oversees the domestic and sexual violence Napuha Kha Nii programs, on Duck Valley Reservation, where the Shoshone-Paiute Tribes live, looks over case files and documents. Owyhee, NV. Sept. 8, 2023.

(Photo: Camalot Todd/Nevada Current)

Domestic abusers often evade the legal system with many cases being underreported, but on reservations, a lack of coordination between federal, state, and tribal laws makes prevention and prosecution even more difficult.

Non-Native people commit an overwhelming amount of domestic violence against Native women and men, according to a 2023 report by the U.S. Department of Justice, but despite being sovereign, federally recognized tribes do not have the authority to prosecute non-Native perpetrators.

“We have our laws, but we are incapable of holding non-Native Americans accountable,” said Kathy Gibson, the rural project coordinator for the Napuha Kha Nii Programs, the domestic violence and sexual assault programs for the Shoshone-Paiute Tribes on the Duck Valley Indian Reservation. Just over 2,000 are enrolled in the tribe with just under half living on sprawling 289,819 acres that make up the reservation.

Tribes do have the ability to arrest and detain non-Natives and deliver them to state or federal authorities for prosecution – but experience has shown the process doesn’t always go smoothly, leaving families and children tied to their abusers.

Madalyn Porath, who works for domestic and sexual violence Napuha Kha Nii programs, drives through the Duck Valley Indian Reservation, where the Shoshone-Paiute Tribes live. Owyhee, NV. Sept. 8, 2023.

(Photo: Camalot Todd/Nevada Current)

Gibson and Madalyn Porath, the only other employee at the domestic violence center, witnessed this unfold before between a Native woman and her non-Native boyfriend involving strangulation and firearms.

“In her words, ‘he just decided he wanted to hurt me’ and she said it like it was just another day,” Porath said.

A neighbor overhearing another assault between the couple called the police at the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), which can’t arrest non-Natives.

In the days after, a complicated web of legal jurisdiction needed to be untangled: what happened, with whom, and where it happened all factor into whether the tribe, the local government, or the federal government has jurisdiction over the criminal case.

The BIA can hold a non-Native temporarily before transferring them to the local or federal authorities — in this case, the Elko Police Department, who at first denied that they had jurisdiction over the non-Native man until Gibson reminded them of Public Law 280, which grants states authority to prosecute crimes on tribal lands committed by non-Natives towards Native American.

“I had to call all the way up to the District Attorney’s office, the FBI, the Attorney General to say, ‘Hey we’ve got a case here and we need to make sure this person is prosecuted or held and does not come back,’” Gibson said.

In situations like what unfolded, that murky jurisdiction plays a large role in the safety of Native women, children, and men on the reservation.

“What would happen if Kathy wasn’t on the phone? You don’t want to think about if this non-Native perpetrator would get away with it, but really what would happen if she didn’t push through?” Porath said.

The case is still ongoing.

Pushing for federal policy changes

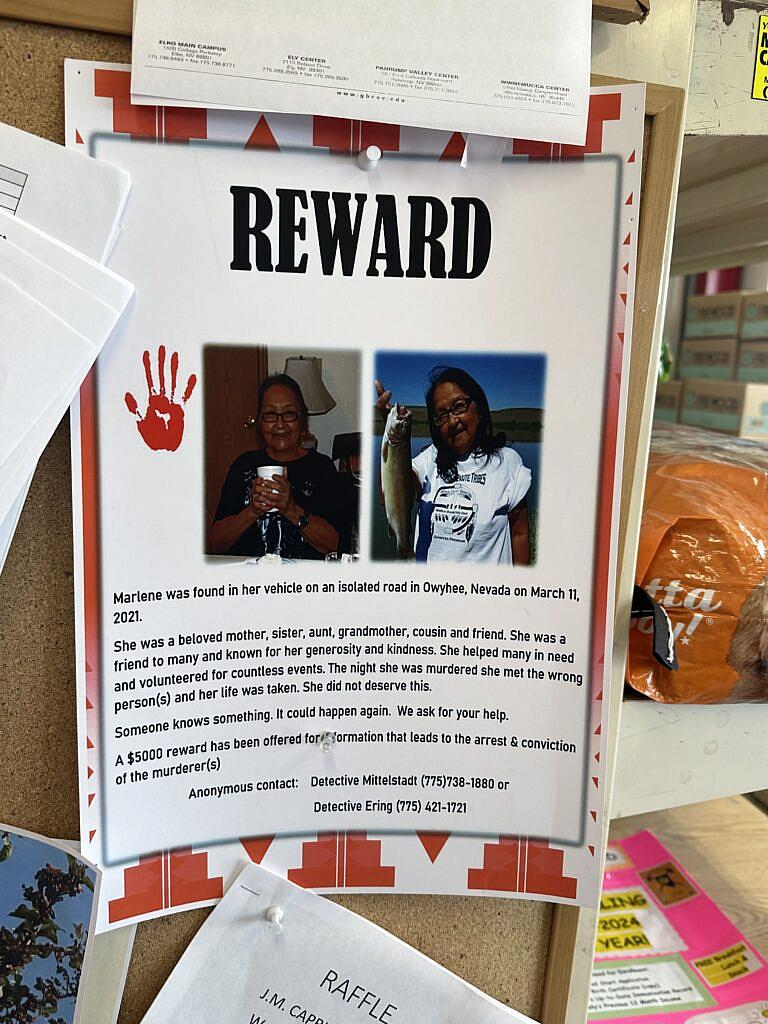

A reward poster for information of Agnes Marlene Thomas death, who was found dead in her car on the Duck Valley Reservation. Owyhee, NV. Sept. 8, 2023.

(Photo: Camalot Todd/Nevada Current)

The Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2022 (VAWA 2022) partially corrected the question of jurisdiction by providing special domestic violence criminal jurisdiction to federally recognized tribes like the Shoshone-Paiute tribes of Duck Valley Indian Reservation. But it operates as an opt-in policy, not a unilateral right.

Tribes have to meet requirements to participate in the VAWA 2022, including having a jury selection that does not exclude non-Native Americans, free, appointed, licensed attorneys for defendants, recorded criminal proceedings, law-trained Tribal judges who are also licensed to practice law, and more.

The DOJ Office on Violence Against Women did not respond at the time of publication with how many tribes nationally nor how many tribes in Nevada meet these requirements and are opted-in to the program.

U.S. Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto (D-NV) is leading bipartisan efforts to strengthen Tribal law enforcement through the Bridging Agency Data Gaps & Ensuring Safety (BADGES) for Native Communities Act.

The law would address breakdowns between tribal and federal governments by using grant funds to support investigations into murdered and missing Indigenous people and sexual assault cases. Cortez Masto also passed the Not Invisible Act and Savanna’s Act, with bipartisan support in 2020. The laws aim to improve the federal response to missing and murdered Indigenous people by increasing coordination between federal, state, tribal, and local law enforcement agencies.

“The crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women and children has been overlooked for far too long, and I am focused on making sure law enforcement can hold perpetrators accountable,” Cortez Masto said in a statement to the Current.

The BIA estimates there are approximately 4,200 missing and murdered cases that are unsolved, including Agnes Marlene Thomas, who was found dead in her car on the Duck Valley Reservation on March 12, 2021.

The National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center notes that domestic violence and the high prevalence of missing and murdered Indigenous women are connected to the messy web of legal jurisdiction stating “the lack of accountability for such crimes are clearly tied to this federal intrusion, the erosion of Tribal authority, and the federal government’s failure to fulfill its trust responsibility to safeguard the lives of Native women. Today, this crisis continues with the limited federal prosecutions of perpetrators and the high rate of federal case declinations by United States Attorneys in crimes of domestic violence, sexual assault, sex trafficking, and murder in Indian country.”

There are no clear guidelines or avenues for tribes to pursue legal recourse for non-Native perpetrators on the reservation — for smaller tribes like the Shoshone-Paiute Tribes, the resources and staff to navigate these systems aren’t there.

“We don’t have a sheet that says A, B, C, and D,” Porath said.

Isolated, without a domestic violence shelter, many can’t leave

Welcome sign to the Duck Valley Reservation, where the Shoshone-Paiute Tribes live. Owyhee, NV. Sept. 8, 2023.

(Photo: Camalot Todd)

As domestic violence cases work their way through the judicial system, survivors and their children are faced with another concern — finding a place to live away from their abuser.

Across Nevada, housing was the most commonly unmet need for domestic violence survivors, according to the National Network to End Domestic Violence’s (NNEDV) 17th Annual Domestic Violence Counts report, released in March 2023.

The State of Nevada’s budget for the next two years does not include any dedicated funds for domestic violence shelters, although some nonprofits can use grants to help find shelter.

“Domestic violence programs continue to face insufficient funding at the federal, tribal, state, territorial, and local levels. This funding can mean the difference between staying with an abuser or safely leaving. It’s unacceptable for survivors to be denied the help they need, often leaving them with no choice but to remain with an abuser and vulnerable to further violence, potentially with deadly consequences,” Monica McLaughlin, NNEDV’s senior director of public policy, said in a press release.

Years ago, Duck Valley Indian Reservation used to have a domestic violence shelter — across from where Gibson and Porath work — but it closed between 2014 and 2015 due to flooding and mold. It offered protection in an isolated frontier community without forcing survivors of domestic violence and their children to relocate from their homes, school, work, and social safety networks.

But now, like a handful of buildings on the reservation, it is condemned. Instead, Gibson and Porath take the survivors who need shelter to Elko or Idaho. State Route 225, the two-lane highway that leads to the Duck Valley Indian Reservation cuts through Owyhee, Nevada, the reservation’s town center which straddles the border of Nevada and Idaho and is nearly 100 miles from a city in either state.

“Not having a shelter here means people don’t want to come in. They don’t want to leave a hundred miles to Elko or a hundred miles to Mountain Home (Idaho) or even further to Boise because they have kids, they work, they have family, support, and structure here,” Gibson said. “A lot of the time I can’t get them into the shelters because they’re so full so I have to resort to other kinds of shelter.”

Stickers outside the domestic and sexual violence Napuha Kha Nii programs building, on Duck Valley Indian Reservation, where the Shoshone-Paiute Tribes live. Owyhee, NV. Sept. 8, 2023.

(Photo: Camalot Todd/Nevada Current)

There are no tribally-operated domestic violence shelters on reservations, according to the Indian Health Service (IHS) public affairs office. But IHS said in an email to the Current that the Intertribal Council of Nevada provides support services and temporary housing through agreements with local hotels in Reno and Las Vegas — about 380 and 530 miles away from Owyhee.

“This can be challenging for remote locations such as Duck Valley,” IHS acknowledged in an email to the Current.

Isolation, violence, and a patchwork of laws determining legal jurisdiction all collide to create substantial health inequities for Native Americans including higher risks of violence in childhood, heart conditions, diabetes, and higher rates of adverse childhood experience (ACEs) than their white peers, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Exposure to violence in childhood increases the likelihood of entering an abusive relationship or becoming an abuser — a boy who sees his mother being abused is 10 times more likely to abuse his female partner as an adult and a girl who grows up in a home where her father abuses her mother is more than six times more likely to be sexually abused than a girl who didn’t, according to the Office of Women’s Health.

“They’ve just seen it from generation to generation be passed down and down, and you just deal with it and you just stay with the person you’re with, or it’s okay for the perpetrator to act how they do and I’m the victim but that’s just how it is,” Porath said. “The cycle continues. That guy may be abusing his wife and their kid sees it and hurt people hurt people and it just keeps going and going.”