Undocumented and Abandoned. The Story of the Punjabi Farmworker

The story was originally published in India Currents with support from our 2023 California Health Equity Impact Fund Fellowship.

Amarjit Singh Sohi works on a walnut farm in Dixon, Vacaville.

image courtesy: Ritu Marwah

An undocumented journey

After a horrifying and long journey, Amit Kumar crossed the border into the United States of America eight months ago. He had realized his dream of coming to America. Kumar had left his small town of Panipat, 64 miles outside India’s capital city of Delhi, and is now living 64 miles outside California’s capital, Sacramento. 7000 miles away from home, away from everyone he loved and cared for, away from the sights and smells of his youth. He is forlorn and lonely. He has no one to look after him.

When asked, “What if you fall sick?” Kumar shrugs. “Falling sick is not an option,” he replies. “I am undocumented.”

Challenges to getting healthcare for undocumented farmworkers can be many- transportation, language, neglect, or a fatalistic attitude towards health.

“Sometimes they haven’t saved enough money for a bus fare,” says Ray Pedden, CEO of Heuristic Associates, who is responsible for the design and implementation of methods and processes to better serve underserved populations. Often, healthcare has to be culturally sensitive.

Raj Sharma, who owns 3000 acres of walnut orchards in Yuba County, is the backbone of his city, Wheatland. He feels a farmworker can’t afford to spend a day getting medical attention for a cut finger. There is no medical clinic in Wheatland.

Raj Sharma Wheatland’s Walnut King

image courtesy: Ritu Marwah

But Pedden urges “The care that they need, especially preventive care, like cancer screening, hypertensive monitoring, and diabetes prevention, all the things that will prevent catastrophic disease as much as possible must be done.”

Rachel Farrell is CEO of Harmony Health which runs five Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHC) in neighboring counties. She is opening the first medical clinic in Wheatland in July 2023, to do just that. However, says Farrell, “A lot of the time while they are waiting for documents they can’t collect entitlements.”

Undocumented Indian migrants cross Mexican border

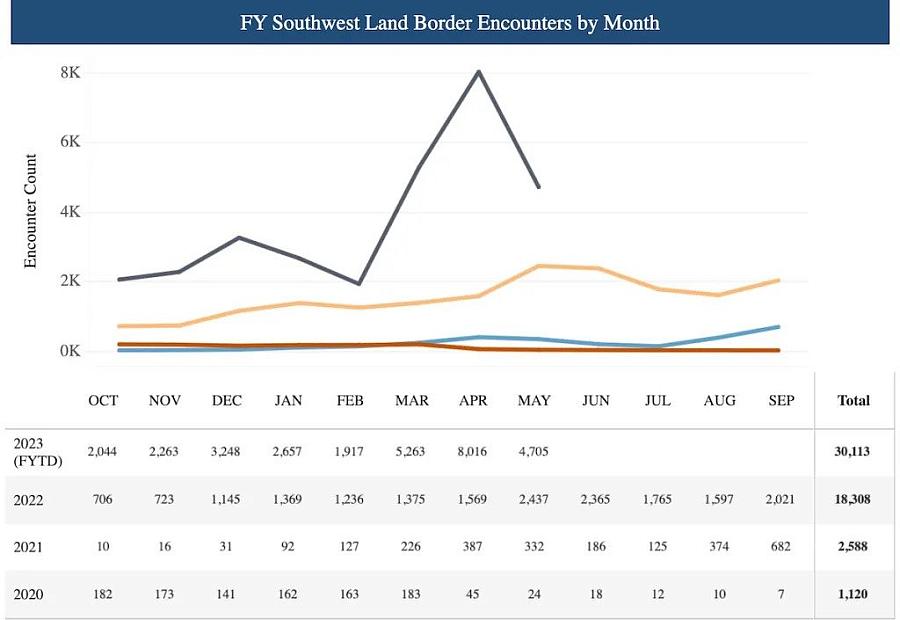

Indians are the sixth largest group to cross the US-Mexico border. This number has been increasing over the years. U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) data revealed that between 2007 and 2018, along the southern border with Mexico, Indian apprehensions increased from 76 to 8,997. Border authorities encountered 15,700 Indian migrants between October 2020 -September 2021, 18,300 in the same period in 2022, and 30,113 in the eight months from October 2022 to May 2023!!

U.S. Customs and Border Protection encounters with Indians at the Southwest Land Border with Mexico 2

image courtesy: Ritu Marwah

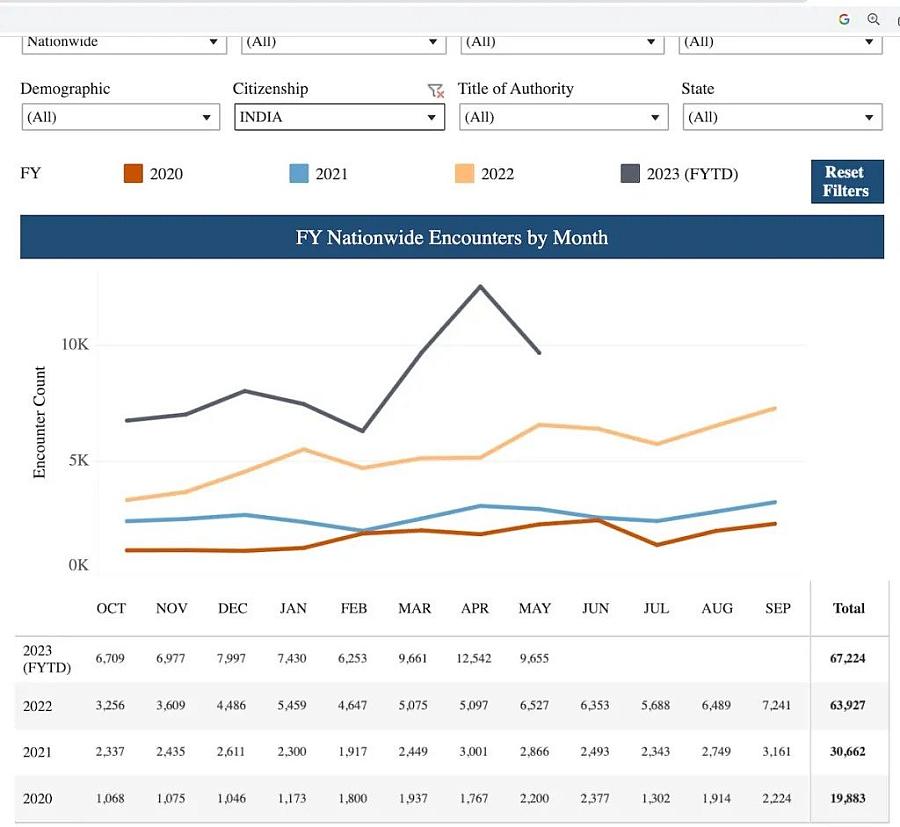

Nationwide the figures of CBP’s encounters with immigrants from India show a jump from 19,883 in 2020, to 30,662 in 2021, and 63,927 in 2022, to 67,224 in the 8 months of October 2022 to May 2023.

Nationwide U.S. Customs and Border Protection Encounters with immigrants from India

image courtesy: Ritu Marwah

Given the growing number of this cohort, its impact on the cost and efficiency of the healthcare system must be planned for.

Stanford’s MASALA Study

South Asians in America are 40% more likely to be diagnosed with diabetes than the white population, despite having lower average BMIs.

Stanford’s MASALA study (The Mediators of Atherosclerosis in South Asians Living in America (MASALA) Study) is the first longitudinal study of U.S. South Asians to understand what factors lead to heart disease and to guide the prevention and treatment of heart disease. It found that South Asian Americans are at high risk for diabetes even with lower body weights. Rather than under the skin around the hips or thighs, Asian Americans tend to deposit fat in the liver, around the abdominal organs, in the muscle, and around the heart.

The MASALA study recommended that Asian Americans get screened for diabetes at a body mass index of 23, instead of the BMI of 25 recommended for the general population.

Maria Rosario Araneta, an epidemiologist at UC San Diego adds that many Asians may have diabetes at lower A1C levels. That means many Asians with diabetes could progress undiagnosed for years until complications with their eyes or kidneys arise. To catch these missed cases, she and other researchers recommend that Asians with A1C levels that fall in the “prediabetes” range – 5.7% to 6.4% – get referred for further testing, to more accurately determine whether they have diabetes and need interventions.

Amit Kumar’s Story: From Panipet To Sacramento

Kumar is new to the United States and its cuisine. He lives in a food desert and has little time to seek out and cook fresh food. Working three jobs to make ends meet he has no time to test for a medical condition that he doesn’t even know he could have.

The stress of his recent harrowing journey from India to the U.S. may have had an impact on his medical condition that he has no idea he is genetically predisposed to.

A billboard promising a U.S. visa for just $150 had appeared in Kumar’s hometown. After several small payments, an agent slowly reeled him in and finally informed Kumar that the process would cost $30,000. At this point, Kumar was reluctant to lose the money he had already paid the agent.

The fear of disappointing his family and the lure of America kept him going. After making the payment Kumar waited months before he was informed he would be using the “Donkey process” to cross into the U.S. – that is, he would be entering the US as an undocumented person. No direct flight to the US was possible.

Wheatland’s farms employ migrant farmworkers

image courtesy: Ritu Marwah

The Donkey process

The journey – by bus, train, or on foot – usually starts in a Latin American country like Brazil, Honduras, or Ecuador. The border crossings, facilitated by “donkers” aka coyotes take months not days.

At every border, Kumar waited for his donker to contact him. While he waited, there were times he had no roof over his head nor a bed to lie on. He said sometimes for days or weeks he slept in the open, in the rain and cold. From Ecuador, he went to Columbia, and then along the “death river” of the jungles of Panama, before he entered Mexico.

“With every passing day, I realized what a mistake I had made,” said Kumar. During the grueling ordeal, when people start falling sick, the donker slowed down for no one. “Children, ladies, old people who can’t keep up were shot dead by the donker,” Kumar added. “I have seen it with my own eyes.” The images of abandoned, drowned, and dead fellow travelers who had been too weak or unlucky to keep up, stayed with Kumar as he entered Mexico.

The deadliest land crossing

The deadliest journey is the one through Mexico. Gang violence is high. If unlucky, a migrant’s organs can be auctioned off. Money, phones, etc. are stolen leading to death by starvation. Some drown and some pass out due to the excessive heat and humidity.

The International Organization for Migration, a United Nations-affiliated group, recorded more than 1,200 deaths of migrants in the Western Hemisphere in 2021. It tracked 728 migrant deaths along the U.S.-Mexico border, calling it “the deadliest land crossing in the world.”

From Mexico, Kumar crossed into a remote part of Arizona. It was close to where a migrant called Gurupreet had gotten lost in the desert and died of heatstroke, while her mother had gone searching for water.

Applying for asylum

Once Kumar crossed the border he applied for asylum. He waited for 150 days to get his Employment Authorization Document (EAD) or work permit.

“Before Covid, the border crossers feared being caught as they would be jailed if caught. However after Covid and under Title 42 the immigration authorities fingerprint and release them to their guarantor. The border crossers want to be arrested,” explained Sharma. “Once arrested they are given a path to become documented.”

“The agent in India sets up the guarantor for the border crossers,” explains Sharma. “The guarantor rents a place for $2000 a month and at a rent charge of $500 per person per month, he packs over 10 people into an apartment while they wait for their turn at the immigration office. He places them in jobs and promises to attend their court hearings when they can’t make them.”

Wheatland in Yuba County has no health facility

Kumar’s guarantor set him up in Wheatland, Yuba County, California. It’s a place where he has no family or friends. “The population of Wheatland is 40 percent white, 40 percent Hispanic, and the rest everybody else,” said the school secretary of Wheatland Union High School. It is 5 % Asian, according to the school website.

Historically speaking, in the 1840s, Wheatland was considered the end of the Emigrant Trail. It was the first settlement reached by the overland immigrants, after crossing the Sierra, like the Donner party after they were rescued in 1847.

The ladies at the Salle Orchards farm stand said that Wheatland is plumb between San Francisco and Tahoe, two hours from each city. Wheatland has the Hard Rock Casino and Hotel and the Toyota Amphitheatre, which hosts names like Bruno Mars.

But Wheatland has no medical facility.

Wheatland’s clinic on wheels

Harmony Health’s clinic on wheels at Wheatland High, every Wednesday

image courtesy: Ritu Marwah

Eight months ago Harmony Health began offering physicals every Wednesday, via a medical mobile unit parked at the high school. This ‘clinic on wheels’ made getting their physicals easier for high schoolers.

These federally funded nonprofit health centers or clinics provide comprehensive primary and preventive care to medically underserved areas and populations. They provide primary care services regardless of the patient’s ability to pay or their health insurance status. They provide services for health, oral hygiene, mental health, and substance abuse to persons of all ages, on a sliding scale fee based on their ability to pay.

Rachel Farrell, CEO of Harmony Health

image courtesy: Ritu Marwah

“The charge can be as low as $25. If someone can’t pay that we don’t charge them,” said Harmony Health CEO Rachel Farrell. It’s hard for farmworkers to make time to come in for screenings but Farrell has a van service that can bring them in.

“Low-income people work three jobs and they have no time to see the doctor. We do what is called deferred maintenance. We screen them for cancer, high blood pressure, and diabetes. They have never had their blood pressure taken or swaps done, especially the migrant patients. We see a lot of diabetic, a lot of breast and cervical cancer patients,” added Farrell.

Amit Kumar, though he does not realize it, fits the bill for a patient with diabetes and high blood pressure, the silent killer.

Chronic health problems drive medical costs

According to the 20-80 rule, 20 percent of patients account for 80 percent of the healthcare system’s cost, says Shiva, an executive in a medical billing company.

“Chronic heart problems, chronic diabetes, and cancer have been the main drivers of health costs,” he says. “For the health provider, say Medicare or Medi-Cal it is more cost-effective and efficient in the long run to manage the care of this 20 percent rather than have them show up in the Emergency department of a hospital with a $100,000 cost.”

Wheatland’s first medical clinic getting ready for its debut in July 2023

image courtesy: Ritu Marwah

Amarjit Singh Sohi works on a walnut farm

Amarjit Singh Sohi is new to the United States. He has been granted asylum. His wife and two children traveled with him from Dubai where he ran a logistics business. He works on a walnut farm of a Hindu family in Dixon Vacaville.

His disappointment is deep. He had really hoped for the community to create institutions that would support undocumented people while they wait for their work authorization known as Employment Authorization Document (EAD). He points out two undocumented workers working nearby. They are struggling to eke out a living and put a roof over their heads.

“Nobody gives them a job,” he says.

The workers had no place to live till a white family adopted them and gave them a place to stay. Manjit, the kindhearted owner of a nearby Punjabi eatery gives them food when possible.

Amarjit Singh Sohi

image courtesy: Ritu Marwah

Social determinants of health

Ray Pedden points out the importance of social determinants of health published by the World Health Organization (WHO).

“We have data now that suggests that people who are unhoused, their health status outcomes improve if they can get into stable housing,” says Pedden. “They may have diabetes, hypertension, they may be obese, they may suffer from kidney disease. What we have seen from the data is that if we can get them into stable housing right now we are able to address their health needs.”

Diet and exercise are key to diabetes control, states the MASALA study ‘The South Asian Healthy Lifestyle Intervention (SAHELI) Trial: protocol for a mixed-methods, hybrid effectiveness implementation trial for reducing cardiovascular risk in South Asians in the United States‘, states that diet and exercise are key to diabetes control.’

Culturally Sensitive Intervention

SAHELI points out that “existing interventions often do not reach immigrant populations because of a mismatch between the social, cultural, and environmental context of immigrants and Western bio-behavioral models.”

Their hypothesis is “behavior change strategies with culturally-adapted strategies and group motivational interviewing to improve diet, physical activity, and stress management” will deliver “greater improvements in clinical ASCVD risk factors (weight, blood pressure, glycated hemoglobin, and lipids).”

“As a white male when I seek out healthcare I want it to be fast and efficient,” says Pedden, pointing out that different strategies work for different people. “I want healthcare now. The Hispanic patients on the other hand felt, they first needed to establish a relationship with and build trust with the provider.”

Ray-Pedden-CEO-for-Heuristic-Associates

image courtesy: Ritu Marwah

Ohana helps to keep health goals

Indian Americans are what Pedden calls Ohana.

In India, healthcare involves the entire family and not just the patient. When the patient shows up at the hospital, members of his family (Ohana) will come along with them.

When working with this cohort, the wider inclusion of family and friends to support an individual in adhering to health goals is more effective. In a medication adherence project in Petaluma, Pedden says, “We needed something that the family could read together, a piece of paper that could be put on the refrigerator so everyone could know when the patient is supposed to take their medication, which day, at what time of day and with what. It was designed with the entire family and support system in mind, to help the patient stay on track.”

While considered a personal matter in the U.S., in India, health indicators are discussed with family and friends. It is not uncommon, for instance, to hear details of bowel movements discussed with family and friends. A casual, “How are you doing uncle?” will elicit great detail on what many consider private information. In fact, Bollywood movies will a doctor handing out prescriptions to the family members and making them responsible for the patient’s health when a patient plays truant.

In India, Kumar’s health was not his responsibility but his family’s. Alone in California, Kumar shrugs when asked “What if you fall sick?” He doesn’t have an answer.

“Medication adherence is a challenge that, if solved, could save the healthcare industry between $100 and $300 billion in costs annually,” notes an article published in the Journal of Risk Management and Healthcare Policy. “Estimates are that approximately 125,000 deaths per year in the United States are due to medication nonadherence.”

Bridging the healthcare gap

Companies like GeneClinicX, a Pune and US-based company that runs a health monitoring and improvement counseling service for South Asians are using health management techniques rooted in research, food, and habits of both countries, India and U.S.

They may help bridge the gap.

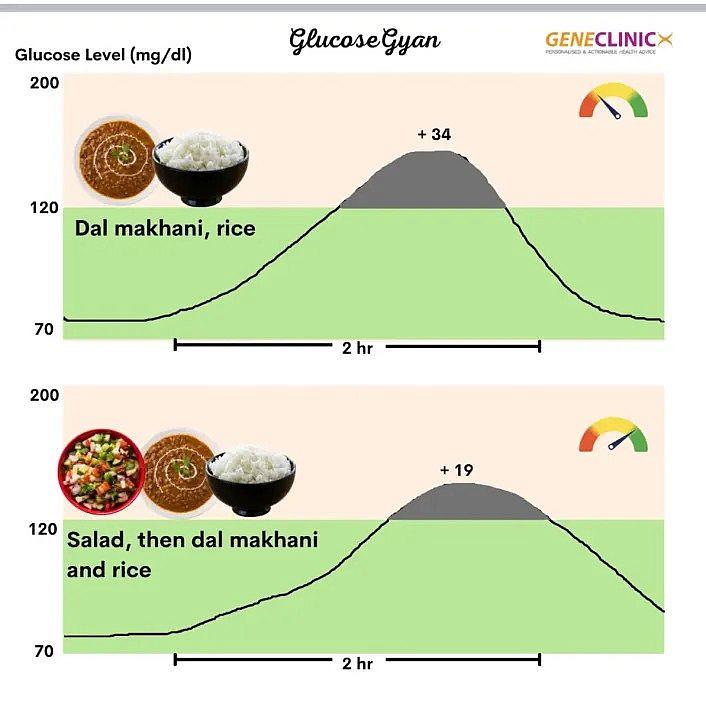

“Small changes can make big differences,” says Nickhil Jakatdar, CEO GEneClinic X. The company’s Glucose Gyan can be accessed over the internet or via Whatsapp messages. Small tweaks deliver large results. For instance, the spike in blood sugar can be controlled by eating the greens or salad on your plate before eating the protein. “It is the spike that is most harmful,” says Jakatdar, “not the A1C which is the average reading of your blood sugar. Eat the carbohydrates on your plate last,” he advises.

“Eat your Salad first, then protein, followed by starch,” says Glucose Gyan

image courtesy: Ritu Marwah

South Asian Heart Center in Mountain View California guides Indian Americans on lifestyle management as a way to stave off diabetes and heart disease. Their volunteers call the members on their list once a year and guide them with simple hacks. After listening to the person’s diet and exercise behavior they add, “Could you add 12 nuts to your daily diet? Could you walk for ten minutes after every meal? Is your meal plate half vegetables, a quarter protein, and quarter carb? What can you do to get 7 hours of sleep every day?”

Pedden, who works with Dr. George Lee at Asian Health Services (AHS) in Oakland, in the use of medi-tech has achieved great results in the control of blood pressure and diabetes among patients. “The results were very, very good with texting. People today, especially the younger population respond extremely well to texting and it does not require a lot of human labor to allow that to happen. And if you understand the cadence that is most effective- once a day, once a week, once a month,- what is the cadence that is working with the patient to get the best results, texting can be a great tool.”

“Messages sent at the right frequency and time of day can be effective,” he said.

When asked about the value of texting, Sharma says, “A person who sells sprouted beans came to meet with me and when I complimented him on how good he looked he told him he used to be obese and lost all his weight after he disciplined himself not to eat after eight in the evening. Now this gentleman texts me every day.”

“It is eight o’clock, time to put away your snacks Raj, And I can tell you it has made a big difference to my health,” says Sharma.

Raj Sharma, Walnut King of Wheatland

Raj Sharma and his family came to Yuba County in the 1980s. His father, Ram Rattan Sharma was a farmworker. Like Amarjit Singh Sohi, Ram Rattan toiled in the fields. At 57 his heart stopped beating. The family was shattered. Help was 100 miles away in Marysville.

“I called 911. Put my dad in the car and raced towards the ambulance. The medical facility was 100 miles away. We met the ambulance on the way. It was too late for my father.”

Raj Sharma at his organic vegetable farm in Dixon

image courtesy: Ritu Marwah

For years, Sharma and the city had tried unsuccessfully to attract health professionals to Wheatland, until Farrell. In July, Rachel Farrell will open Harmony Health’s clinic in a building owned by Raj Sharma.

It will be Wheatland’s first clinic.