What it’s like to go to school when dozens have been killed nearby

Sonali Kohli worked on this project while participating in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism's 2018 California Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

Resources for students and families affected by violence near schools

How should journalists write about killings near schools? The students weigh in

Police respond to a crime scene near Hawkins High School.

(Photo Credit: Marcus Yam / Los Angeles Times)

By Sonali Kohli and Iris Lee

Jaleyah Collier had just said goodbye to Kevin Cleveland outside a doughnut shop a few blocks from Hawkins High School on a spring afternoon in 2017. Get home safe, she told him before walking away.

Minutes later someone drove into an alley nearby, got out of the car and asked Kevin, 17, and two others about their gang affiliation. The gunman then sprayed them with at least 10 rounds, killing Kevin and injuring the others.

Jaleyah, then a high school sophomore, barely had time to grieve when a month later, her best friend, Alex Lomeli, 18, was shot and killed when someone tried to rob a market about a mile from the same high school, located at 60th and Hoover streets.

In the early hours of Mother’s Day 2018, two other teens Jaleyah was close to, Monyae Jackson and La’marrion Upchurch, were walking home with friends, when they were fatally shot near Dymally High School.

Each of Jaleyah’s friends was killed within walking distance of public high schools in Los Angeles.

“You don’t know when it’s going to be a person’s last day,” said Jaleyah, a senior at the Community Health Advocates School, one of three small schools on the Hawkins campus. “[Kevin] woke up not knowing.”

While much of the recent national conversation on campus violence has focused on mass shootings, schools also are dealing with other physical and psychological harms that thousands of students experience directly or indirectly near campuses.

The impact of that violence can be devastating and costly. Campuses have begun incorporating the inevitability of trauma into their curricula, addressing stress reduction and how to settle differences without resorting to violence. Students suffer symptoms resembling post-traumatic stress disorder and psychiatric social workers are now a staple at many campuses. Because there is too little mental health funding to meet the need, teachers and staff are often on the front lines in identifying the warning signs of emotionally needy students.

One concern is practical: getting safely to and from school, avoiding not just bullets but gang flashpoints, street harassment, hit-and-runs and muggings. With limited district busing, some students opt for public transportation or other ride-sharing options. On their journeys, they sometimes pass candle- and flower-filled memorials to fallen friends.

Sixteen-year-old Carl Hull, a sophomore at Dymally High School, starts his walk to school each morning by turning into an alley to avoid gang members who live on his street. Once, when he was wearing a gray sweatshirt with the blue L.A. Dodgers logo, they stopped him and asked about his affiliation — he’s not involved in gangs, he told them. Another morning, a few days after hearing gunfire near his house, he found a 9-millimeter bullet shell. Each day, he said, is “like a guessing game.”

Carl Hull, a 10th-grader at Dymally High School, follows a route he feels is safest to get to school. (Photo Credit: Marcus Yam/Los Angeles Times)

Decades of research suggest that the effects of exposure to violence on teenagers are wide-ranging, and can result in anxiety, depression, anger, absences and an inability to concentrate in class.

Even if students didn’t know the victims, they see reminders on social media, memorial posts and the T-shirts friends and family wear in trying to raise funds for a funeral.

Jaleyah woke up on Mother’s Day to find her Instagram feed filled with posts about the shooting of Monyae and La’marrion, she said.

Children in high-crime areas are “losing more people in their youth than most of us have lost when we get to 30 or 40,” said Ferroll Robins, executive director of the nonprofit organization Loved Ones Victims Services, which provides counseling for victims of violence and their families.

“I do worry about what is going to happen to them emotionally, mentally, how bad are they really being scarred?” Robins said. “And how much of those scars are going to play into their life later?”

Jaleyah Collier hugs her friend Shelsea Reyes, 17. (Photo Credit: Marcus Yam/Los Angeles Times)

Jaleyah, a bubbly and energetic 17-year-old, prides herself on her resilience but resents that this constant drumbeat of loss is her reality. In the days after a friend dies, she is unable to concentrate in class, she said. She goes to the funerals, some during the school week. She’s nervous walking to school, afraid a man with a hoodie pulled over his head might be hiding a gun, afraid to walk in alleys or on side streets. She feels a jolt whenever she sees her slain friends’ photos or someone mentions them, reminded each time that their lives had ended too early.

Processing trauma in the classroom

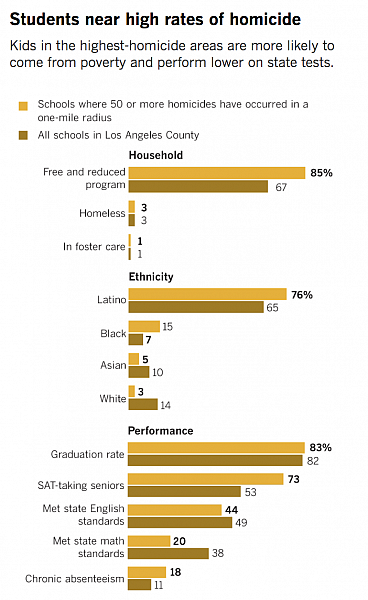

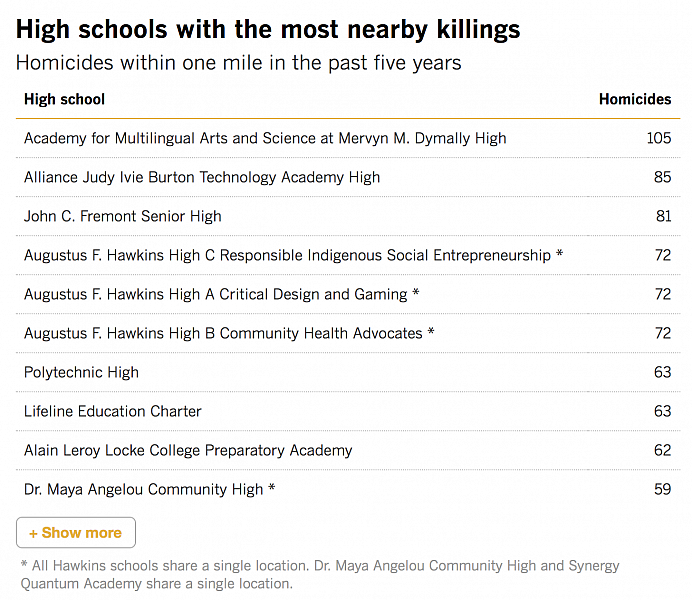

Jason Powell knows he can’t begin teaching his English and music classes at Dymally, at 88th and San Pedro streets, until the kids can address the latest violence in their lives. Over the last five years, 105 people have been killed within a mile of the campus, the highest number surrounding any public high school in the county. Ten of the victims were 18 or younger.

Last year alone, 20 people were killed within a mile — about one every 2½ weeks. Sometimes they are current or former students, including Monyae.

After the deaths of La’marrion and Monyae, Powell gathered his ninth-graders in circles during class and asked them how they deal with pain. The students were used to sharing because they have these circles often on subjects both mundane and serious.

The exercise was intended to develop positive coping and conflict resolution skills. One by one, the students took turns sharing stories of loss. Similar scenes played out at several area schools where students had known the boys who were killed.

When a friend dies, “they come in welled up with emotion, they’re crying and there’s no way they can concentrate on the lesson at hand, so whatever’s on the board as far as the lesson plan, that means nothing,” Powell said. “They need more immediate help.”

Jaleyah said that seeing the therapist on campus didn’t help her, but that participating in similar community circles at Hawkins taught her how to voice her anger and channel it into action. “They give us a chance to speak and feel free [in] what we have to say, without being afraid,” Jaleyah said.

Sometimes the loss is unrelenting. As Dymally was preparing for graduation just weeks after former student Monyae’s death, there was more tragic news: Campus aide James Lamont Taylor was killed at 8:30 a.m., walking on the street about a mile from the school.

The journey their children take just getting to school is a source of stress also for parents.

Carl’s mom worries about him getting robbed or shot on the way to Dymally, or hit by a car while crossing the street. Her older son, Brian Hull, was killed in 2016 crossing the street near her home. She and Carl have grown used to hearing gunshots from their apartment in Broadway-Manchester, less than a mile from the high school. She’s afraid that when he walks down the alley behind their home to get to school, he’ll get hurt.

“I have real bad, heavy anxiety,” Latanya Hull said. One afternoon in September, she began to worry when Carl didn’t get home at the usual time. His phone was broken, so she couldn’t reach him. She called the school. Carl was there, they said, in after-school tutoring.

Assistant Principal Deon Brady ushers students back to their class in between periods. (Photo Credit: Marcus Yam/Los Angeles Times)

A member of Dymally’s school site council, Hull said she wants to see staff pay more attention to the climate on campus and try to understand the root of students’ problems rather than suspending or arresting them. For example, she praised the school’s assistant principal, Deon Brady, because he gets to know students on campus, welcoming them in the mornings and mingling at lunch. He takes parents’ concerns seriously, Hull said.

Creating mental health resources

Educators know the violence outside of schools affects children after the morning bell rings, and they are trying to find ways to mitigate it.

When students lose someone, or are afraid of what will happen getting to and from school, they might not show up, or show up and have difficulty concentrating, said Pia Escudero, executive director of student health and human services for the Los Angeles Unified School District. The constant state of alertness is exhausting and can lead to emotional numbness — neither of which is good for learning, she said.

“You look at the kind of complex traumas that some of these young people face, it requires professionals who understand those situations,” said UCLA education professor Tyrone Howard.

While more and more schools are adding full-time mental health workers, some still deploy them only in emergencies — such as when a student or staff member is killed.

At Fremont High in the Florence neighborhood, seven academic counselors have been trained to look for signs that a student may be in mental distress, principal Luis Montoya said. The watch commanders at the local police station have Montoya’s number, so they can alert him when something has happened that might affect his students.

“We work in this community. Your job cannot be an academic counselor only,” Montoya said.

LAPD officers and first responders answer a call from local residents about a boy shot in the foot. (Photo Credit: Marcus Yam/Los Angeles Times)

By his junior year at Fremont, Juan Mercado said, he had witnessed a double homicide at a park in East L.A., a shooting near his home, and had been robbed at gunpoint while skateboarding outside the school. He felt depressed and anxious, always looking over his shoulder, ditching classes and dropping extracurricular activities.

His mentality became: “I’m trying super hard in school, trying to get good grades and everything, for some random dude [to] just like, take that from me and then all of that work will be gone,” he said.

He got the nerve one day in senior year to ask his academic counselor for help. She called a campus-based therapist, who began counseling Juan once a week at school. It was the push he needed to get his grades back on track. He graduated on time and is enrolled at L.A. Trade Tech, with aspirations to transfer to UCLA.

“If she would have told me OK, like, ‘Come back tomorrow or we’ll talk to him tomorrow’ and stuff, I just probably never would have gone,” Juan said.

Designing a school with trauma in mind

The Hawkins campus includes three pilot schools focused on aspects of community health and problem-solving.

Their goal, in part, is to teach students how to deal with trauma before it happens. Incoming freshmen in the community health school take a summer bridge course to learn how stress — in such areas as cyberbullying, body image and relationships with siblings — affects the brain and how to cope.

One program that has shown some success in improving empathy and problem-solving was initially developed for military families — who can experience frequent moves and stress related to deployment — and adapted for L.A. Unified. It teaches students about trauma, how people can be triggered, and how to regulate emotions and manage stress, said Roya Ijadi-Maghsoodi, an assistant psychiatry professor at UCLA. The program is available to more than 5,000 students at 106 schools, including Dymally and the community health school at Hawkins.

Jaleyah doesn’t hold much hope for change in her community. She said she considered leaving to join the Marines, but despite the violence around her there’s a comfort to being home. So for now, she plans to live at home and attend community college after graduating from Hawkins in June. She wants to remember her friends and honor them, but knows they wouldn’t want her grief to hold her back.

“I just can’t be sad forever,” Jaleyah said. “I just got to keep moving on and do what I gotta do so I won’t be in this situation.

“So I can make it out of here. So I won’t die.”

Jaleyah Collier, a senior at Hawkins High School, talks to Andre Vickers of Chapter Two, a local gang prevention program. (Photo Credit: Marcus Yam/Los Angeles Times)

[This story was originally published by the Los Angeles Times.]