When will U.S. apologize for boarding school genocide?

Mary Annette Pember wrote this article, originally published by Indian Country Today Media Network, as a 2014 National Health Journalism Fellow, with support from The Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism. Other stories in her project series can be found here:

Truth and Reconciliation: The road to healing is lond and arduous

'Cultural genocide,' Truth and Reconciliation Commission calls residential schools

6,000 kids died in residential schools: Canada Truth and Reconciliation Commission

Trauma may be woven into DNA of Native Americans

Lakota turn to crowfunding after spate of suicides

A fearless fight against historical trauma, the Yup'ik way

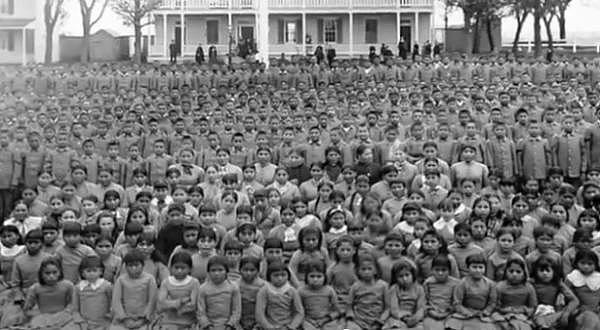

Boarding school students in Minnesota

The cultural genocide perpetrated by Canada’s Indian residential school system was heavily influenced by the United States.

When the Canadian government first sought solutions to the country’s “Indian problem,” back in the 19th century, it turned to the cruel yet expedient example set by its neighbor to the south. A Member of Parliament, Nicholas Flood Davin, suggested that Canadians model their efforts after those established by U.S. Army Lt. Richard Pratt, who founded the Carlisle Indian School in 1879. Pratt coined the infamous phrase, “Kill the Indian to Save the Man” as a motto for the systematic destruction of Native culture, language and family as an alternative to warring against tribal nations.

The U.S. model, however, does not figure highly in Canada’s recent reconciliation efforts. On June 11, Canada marked the eighth anniversary of its formal apology by Prime Minister Stephen Harper to First Nations, Métis and Inuit peoples for the travesty that was Canada’s boarding schools. The apology, financial compensation, a framework for healing and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) were all components of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement in 2007. (In the largest class-action suit in Canadian history, former students of Indian residential schools settled out of court with the federal government and four national Christian churches.) The commission’s mandate since then has been to gather written and oral history of residential schools and survivors and work toward reconciliation between survivors and Canada. The TRC concluded its work in June.

In the Canadian Agreement, survivors specified that part of their settlement go toward funding programs aimed at healing and helping survivors and their families recover from the trauma inflicted upon them by the residential schools. Medical research in Canada (First Nations Information Governance Center) and the United States (American Psychiatric Association) link the boarding school traumas of abuse, neglect and separation from family and culture with high rates of suicide, substance and alcohol abuse, sexual abuse and violence, and other health disparities such as high blood pressure and diabetes. Canadian health professionals note that reducing these disparities requires more than narrow concerns directly related to drug and alcohol abuse; it requires understanding and addressing the historical and cultural impact of trauma on aboriginal peoples.

Despite similar disparities in health for Native peoples in the U.S., the government has never formally addressed its role in the forced assimilation of generations of Native children at government and church run boarding schools. Although President Obama signed an Apology to Native Peoples of the United States on December 19, 2009 into law as part of the Department of Defense Appropriations Act of 2010, the law has received scant media coverage, and Obama signed the bill in private without ceremony or announcement.

Death to Health

Many more Native children were harmed in the U.S. than in Canada by boarding schools. According to the TRC, there were more than 130 Indian residential schools in Canada, and upwards of 150,000 aboriginal children passed through this system. In the U.S., the Boarding School Healing Coalition estimates that there were over 500 such schools. According to Denise Lajimodiere, Ph.D at North Dakota State University School of Education and president of the Boarding School Healing Coalition, there were 153 federal Indian boarding schools and many more religious schools run by Christian denominations through contracts with the U.S.

According to the Native American Rights Fund (NARF) 2013 Legal Review, there were still 60,000 Native children enrolled in boarding schools in 1973, when the boarding school era was coming to a close.

“We need more researchers to verify data here in the U.S. Canada is so far ahead of us,” says Lajimodiere, Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa. She points out that this data is crucial because unresolved trauma from boarding schools has contributed to maladaptive behaviors and social patterns such as suicide, domestic violence and substance abuse.

Health care professionals working in Indian Country say there is a direct relation between the trauma experienced in boarding schools and high rates of depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), drug and alcohol use and suicide among boarding school survivors and their families. According to Teresa Brockie, researcher with the National Institutes of Health (NIH), historical trauma—including the boarding school experience—contributes to high rates of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACES) among Native people, which in turn give rise to mental health problems. The ACES study by the Centers for Disease Control and Kaiser Permanente found a connection between adverse childhood experiences and poor health.

Lajimodiere and other volunteers with the Boarding School Healing Coalition are working to bring the U.S. side of the boarding school story to the public, and help bring healing and justice to survivors and their families. The Coalition has recommended that the U.S. create a Commission on Boarding School Policy, with full participation of Native peoples who were affected. It also says the Commission should provide accurate information to the government and public about boarding school abuses, gather documentation from survivors and their families, receive recommendations for programs to help and support healing for families and communities and document healing programs that work.

Not Allowed to Sue

Statutes of limitations in the U.S. courts regarding lawsuits against individuals or institutions prohibit legal actions like the residential school class action lawsuit in Canada.

“There is no meaningful access to justice in the courts for survivors or communities, therefore the Coalition’s main work is focused on healing,” according to Donald Wharton, an attorney with NARF who works with the Coalition. “We are not saying that individuals are not entitled to financial reparations, but we are choosing to put our energies toward healing.”

He adds that presentations to Congress about the legacy of boarding schools should include a solution and specify a role that government can play in helping Indian country to heal.

U.S. leaders appear to already have some understanding of boarding school history. In her remarks for the White House convening on Creating Opportunity for Native Youth in April,

Michelle Obama said, “Folks in Indian Country didn’t just wake up one day with addiction problems. Poverty and violence didn’t just randomly happen to this community. These issues are the result of a long history of systematic discrimination and abuse. We began separating children from their families and sending them to boarding schools designed to strip them of all traces of their culture, language and history. We should never forget that we played a role in this.”

Obama further promised, “Make no mistake about it—we own this. We can’t just invest a million here and a million there and think we’re going to make a real impact. This is about nation-building, and it will require fresh thinking and a massive infusion of resources over generations.”

Wharton says Coalition members and tribal communities are working with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA) to secure a grant to create a healing model that communities can craft to suit their needs.

Lajimodiere found in her research that survivors and their families want, in addition to a formal acknowledgement of the apology already signed by President Obama, help and support in the form of mainstream therapy and traditional Native medicine. “We need to get Congress to understand that this is a wrong that needs to be righted. The trauma, not only from boarding schools but also from disease, loss of land, just goes on and on in Indian country,” Wharton says. “Any infrastructure for healing also needs to be ongoing and sustainable. It’s not like we’ll just have one event and everyone will be healed overnight.”

Many churches also played a significant role in the boarding school era and therefore will need to be involved in the healing process as well, according to Wharton.

Indeed, the Christian denominations, especially Catholics, fought hard to gain and maintain their schools in Indian Country. ICTMN visited Marquette University in Milwaukee, where all Catholic Indian boarding school records are kept.

Each of the boarding schools was required to submit a complete list of all Native children enrolled to the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions in Washington D.C, the administrative organization that managed government funding to the schools. The archive at Marquette is filled with boxes upon boxes of yellowing forms listing Native children’s names written in distinctive Catholic school cursive handwriting. The schools received funding based upon the number of pupils they had.

Beginning in the early 20th century, that funding came directly from Native trust funds after the Supreme Court found that public monies could no longer be used to pay tuition at religious boarding schools. In Quickbear v. Leupp, the court declared that Native peoples could choose to pay for religious education directly out of their trust funds.

“Choice was a fraught issue in the early 20th century for Native people,” according to K. Tsianina Lomawaima, Ph.D Professor in the School of Social Transformation at Arizona State University. Lomawaima, of the Mvskoke/Creek Nation, has written extensively about the boarding school including the booksThey Called it Prairie Light: The Story of Chilocco Indian School (University of Nebraska Press, 1995) andTo Remain an Indian: Lessons in Democracy from a Century of Native American Education (Columbia University/Teachers College Press, 2006). Although all Native children were not legally required by the early 1900s to attend boarding schools, education was mandatory.

“Entrenched racism kept many Native children out of public schools. Extreme poverty, especially during the Depression years, forced many Native people to send their children to Christian boarding schools,” she notes. Unlike federal boarding schools, religious mission schools were often located closer to reservations, which may also have played a role.Native parents may have simply succumbed to internalized oppression and resignation to the government’s role in their lives, according to Lajimodiere and David Wilkins, Ph.D., professor of American Indian Studies at the University of Minnesota.

“This is important and horrific. We were paying for our own forced assimilation,” Wilkins says.

Assimilation and Death

“There has been a resounding silence across Indian Country regarding boarding schools,” Lajimodiere says. She believes many survivors are stuck in a secondary trauma and are unable to discuss what happened to them at the schools.

TRC Commissioners estimate that over 6,000 aboriginal children died in Canada’s residential schools. The long-forgotten U.S. schools all had cemeteries, many containing unmarked graves, notes Lajimodiere. “We don’t know how many children died in the schools.”

Lajimodiere has spent the past several years interviewing boarding school survivors, many of whom state they were sexually abused at the schools. She has gathered 10 of the most powerful stories and plans to include them in her upcoming book.

She reported that upon hearing she was going to write a book on boarding schools, a non-Native man complained about the large number of publications about them.

“I asked him, how many books are there about General Custer?” she says. “There can never be too many books about the boarding schools, not until we have national attention focused on what happened to our people.”