Would a medical school at UC Merced fix the county’s doctor shortage?

This story is the final in a three-part series. Monica Velez’s reporting on healthcare barriers for low-income residents in Merced County was undertaken as a fellow of the California Health Journalism Fellowship at USC’s Annenberg School of Journalism.

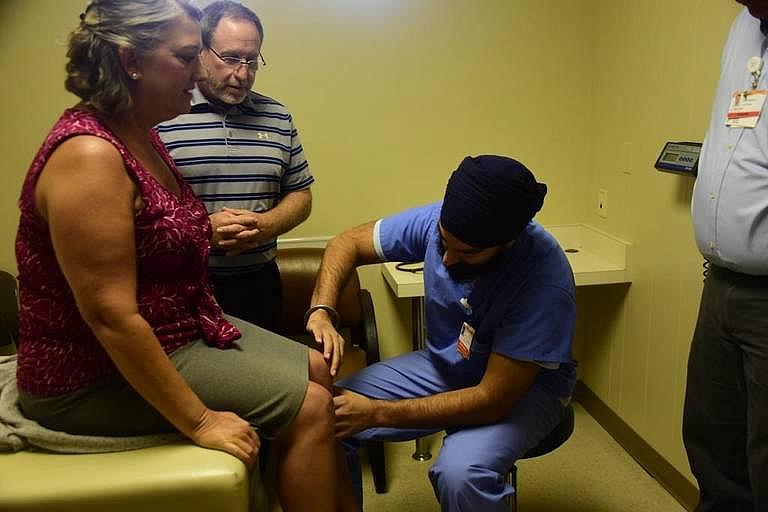

Dr. Gurraj Singh Bedi, a third year resident at the Mercy Medical Center's Family Practice Clinic, exams the knee of Kathy Loucks, 54, on Sept. 7, 2017. Monica Velez

More than 30,000 Merced County residents gained some form of health insurance when Medi-Cal was expanded in 2014.

However, there was no corresponding increase in doctors to accept those patients who suddenly could afford to pay, according to Kathleen Grassi, director of the Merced County Department of Public Health.

“Regardless of Merced or anywhere else, nobody realized how much demand would be generated with Medi-Cal expansion,” she said.

More than half of Merced County residents are on Medi-Cal, which historically has reimbursed doctors less than private insurances.

Paul Brown, a UC Merced professor of public health, said communities with a larger number of people buying private insurance will have a greater number of doctors.

“It has to do with demographics and income,” he said, and the amount doctors make is “if not the most important reason, it’s in the top three in my opinion.”

To help combat the problem, Grassi said, the Alliance has worked in recent years to increase reimbursement rates for doctors who accept Medi-Cal in Merced County.

No short-term solutions, only long-term goals

The closure of Merced-based health clinic Horisons Unlimited, which served a majority of low-income patients in Merced County, sent thousands of people scrambling to find a new primary care doctor in a community already known for physician shortages.

And it seems that every solution is a long-term fix, years away from making a significant difference.

Many Merced-area leaders want to bring a medical school to UC Merced.

Regents gave the Merced university the green light in 2008 to start work on a medical school, but those plans have since stalled.

“What’s frustrating is a medical school was always part of the vision of having UC Merced,” Assemblyman Adam Gray, D-Merced, said in a recent interview with the Sun-Star. “That obviously hasn’t happened. My perspective as an elected official who represents the Central Valley is we have a moral obligation to improve healthcare here and the vehicle we have to do it is the UC (Merced).”

U.S. Rep. Jim Costa, D-Fresno, said more residency programs could bring more doctors to the area and having a medical school at UC Merced is a way to do that.

But it may never happen.

Within the last year, some UC officials have suggested a university medical school might not be the answer to the Valley’s doctor shortages.

At the very least, a medical school is a long-term goal years away and many low-income patients need solutions now.

Establishing medical residency programs in Merced County has been a shorter-term band aid for an quick pipeline to doctors.

Last year, Gray helped bring about $100 million in money from the state to bolster residency programs.

Residency programs, however, also are not a permanent fix because frequently doctors leave the community for higher-paying practices in other communities once their residency term ends.

So, where do we find the doctors?

One possible solution, Gray said, is for Merced County to help put local high school students on a path leading to medical school.

Programs that can encourage younger kids to go into the medical field eventually could ease the doctor shortage in Merced County, said Paul Brown, a public health professor at UC Merced.

Delhi Unified High School is the only district in Merced County that offers a four-year medical program, Delhi Medical Academy of Sciences officials said. Students can either study nursing or general medical training. The program aims to prepare students for college give them a chance to determine if they want to go into a medical career.

The most recent initiative to combat health access by the UC was the San Joaquin Valley Program in Medical Education, or SJV PRIME, established in 2011, according to Brandy Nikaido, director of media relations and public affairs at UCSF Fresno Medical Education Program.

The program collaborates with UC Merced, UCSF Fresno and UC Davis Medical School “aimed at training future physicians specifically to provide care for underserved communities in the Valley,” she said.

Gray worked on legislation to increase the number of slots in the program, adding 1.6 million to the program in 2013.

“That’s a program that’s identifying that population of students who come from here because that’s our best hope,” Gray said. “It helps bring students from the Valley, back to the Valley with the hope that they are going to stay in the Valley.”

Although students aren’t required to practice in the Valley after entering SJV PRIME, Nikaido said, they look for students who have an interest in working with undeserved populations.

“The most impactful thing you can do to bring health care professional into a community is to increase the residency programs,” Gray said.

In the meantime, the Central California Alliance for Health is piloting a program that allows doctors to speak with patients through video chat, according to Dale Bishop, chief medical officer with the Alliance.

“So we’re trying to bring in more providers in. Maybe they’re not in the community but they’ll be available,” Bishop said.

But, long term, many are still hoping for a medical school at the university.

Bishop agreed a medical school would help train people locally, saying it “would be a very good thing” for the community.

“The community can’t dig itself out,” Gray said. “We need some investments that change trajectory of our future and the UC is a big part of that.”

[This story was originally published by Merced Sun-Star.]