Years after fatal crash, a mother awaits change on Highway 9

This story was originally published in the Santa Cruz Local with support from our 2025 California Health Equity Fellowship.

Sidewalk construction is expected to start this fall on Highway 9 between San Lorenzo Valley High School and Graham Hill Road.

(Marcello Hutchinson-Trujillo — Santa Cruz Local)

FELTON >> Kelley Howard sat on the couch in her Scotts Valley home, hands twisted in her lap.

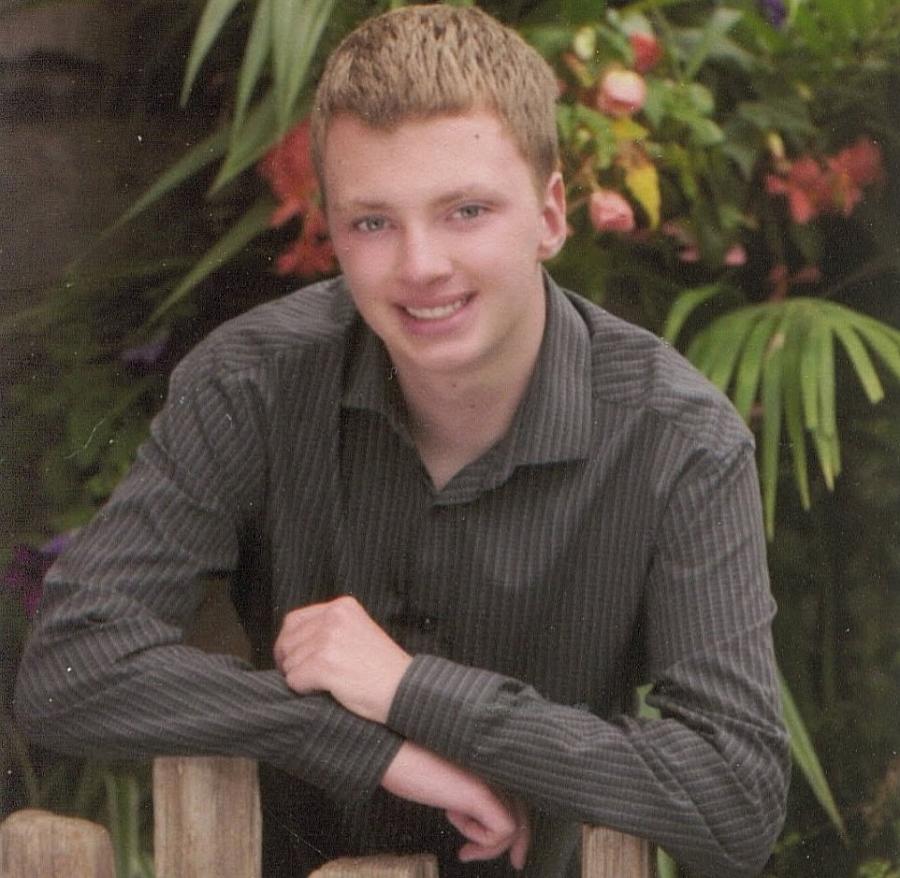

A cat brushed past her legs as four others napped on various perches. One cat was pictured in a framed photo on the mantle, a black ball of fluff held tight in the arms of a grinning blond boy. As Kelley Howard described her son Josh, she slipped between past and present tense.

“Cats were huge in his life, just because he grew up with them,” she said. “But he loves all kinds of animals.”

Josh Howard had autism, and mostly kept to himself. “But if he was talking about trains, or video games, or a movie he wanted to see” — Spiderman was a favorite — “he would talk your ear off,” she said. He often walked his baby sister, Lily, through Henry Cowell Redwoods State Park in a stroller, explaining the mechanical details of different trains.

In 2019 at age 22, he still wanted to live at home with his two sisters and mom, and that was just fine with her. He liked getting around on his own, though he didn’t drive. He took the bus from his Felton home to classes at Cabrillo College, and he regularly walked a mile and a half up Highway 9 to one of his jobs at Castelli’s Deli.

On a late afternoon in February 2019, after a shift at the deli, he started the walk back along the narrow shoulder of the highway towards Graham Hill Road.

Half a mile down the road, a driver drifted out of his lane, slammed into Josh Howard, and killed him.

Kelley Howard later learned that traffic engineers and local transportation advocates had been sounding the alarm about that very stretch of highway for decades, and that state authorities had failed to act. A 42-year-old man was killed in a crash near there in 2017, and a third person was injured in 2024.

California’s rural state highways were designed to keep car and truck traffic running as quickly and smoothly as possible. That has often made them lethal for pedestrians and cyclists, many of whom don’t have other means of transportation. But attempts to redesign stretches of state highways, including parts of Highway 9, have been slowed by red tape and a state agency’s rigid design standards, according to an independent audit and local transportation engineers.

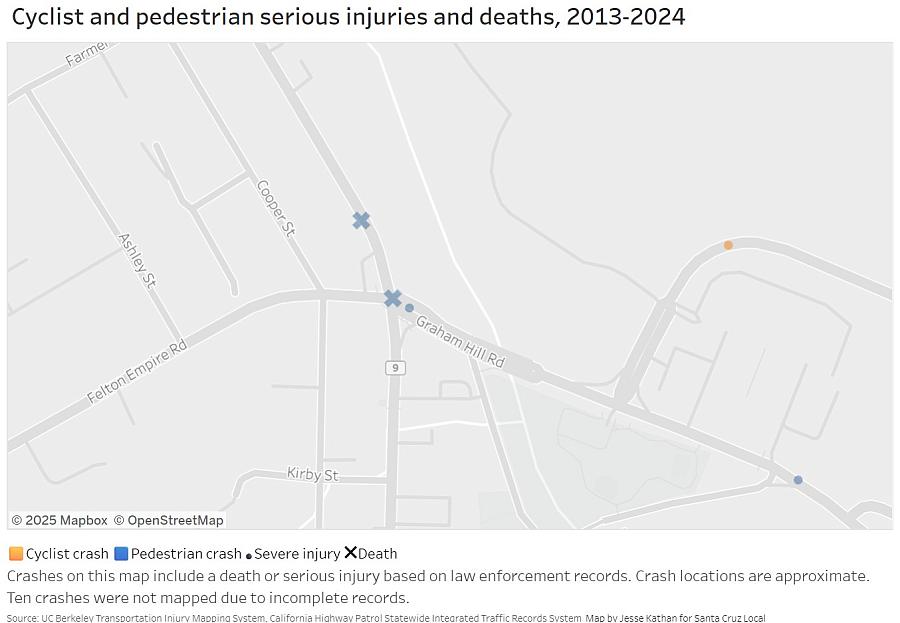

Josh Howard was one of 21 pedestrians and cyclists killed or seriously injured on Highway 9 in the past 10 years. This fall, nearly seven years after his death, construction is expected to begin on a sidewalk alongside that deadly stretch of Highway 9.

Josh Howard was killed on Highway 9 just north of Graham Hill Road in 2019. Another man was killed in a crash in the intersection in 2017, and a third person injured in the intersection in 2024. View full map.

Danger in the mountains

Highway 9 cuts a sinuous path through the dense forest of the San Lorenzo Valley. It’s a main street for rural communities tucked into the redwoods, including Felton, Ben Lomond and Boulder Creek.

Alongside thrill-seeking motorcyclists, carbound tourists and logging truck drivers, it hosts dedicated cyclists, teens who walk between school and home, and older adults who travel by bus and on foot.

Sixty years ago, San Lorenzo Valley was dotted with vacation homes and had few year-round residents. When Ben Lomond resident Jamie Helmer was in elementary school in the 1960s, he and his friends rode bikes down Highway 9. “If there was one or two cars on the road during the school year, that would be a surprise,” he said.

After leaving for graduate school and a brief stint in consulting, Helmer returned to find the population ticking up with more and more full-time residents. By the time he retired in 2010, traffic had grown to a steady stream of tourists and commuters.

With them came more collisions.

On one level, car crashes happen because of individual choices. The driver who killed Josh Howard pleaded no contest to vehicular manslaughter and felony reckless driving, and was held liable for the death in a civil lawsuit.

But street design can make the difference between a safe passage or a deadly encounter.

Helmer is the former director of transportation for the City of San José. He said he helped cut the rate of vehicle crash deaths and serious injuries in the city.

His team’s strategy came down to three E’s: Engineering, education and enforcement. That equates to designing streets to be safer, encouraging drivers to slow down and stay alert, and ticketing or prosecuting drivers who break the law. Though Helmer believes all three elements are necessary, he specializes in design.

Helmer still occasionally consults, but much of the time he uses his expertise to advocate for safer streets in San Lorenzo Valley.

Walking through Ben Lomond, he sees the streets with the affection of a lifelong resident and the analytic eye of an engineer. A slanted crosswalk between the liquor store and hardware store makes pedestrians harder to see. A line of street parking next to a restaurant driveway creates a blind curve where “you’re going to end up with crashes no matter what,” he said.

“We’ve had our fair number of crashes right at that driveway and curb,” he said. “There could have been things done there, like a little bit of ‘no parking’ near the driveway. That didn’t happen.”

Dimitri Jaumouille and Kelley Howard lost their son, Josh, in a fatal crash on Highway 9 near Graham Hill Road in 2019.

(Marcello Hutchinson-Trujillo — Santa Cruz Local)

A sidewalk is expected to open on Highway 9 between Graham Hill Road and San Lorenzo Valley High School in 2027.

(Marcello Hutchinson-Trujillo — Santa Cruz Local)

Helmer said that the part of Highway 9 most dangerous for pedestrians is the stretch where Josh was killed, between San Lorenzo Valley High and downtown Felton.

The shoulder where pedestrians walk is narrow, from 7 inches to 4 feet wide. In many spots, it’s bounded by low retaining walls built in 1990. “It’s a bad stretch, and it always has been,” Helmer said.

Things like that aren’t a concern until something horrific happens

Kelley Howard

Josh Howard in 2015.

(Contributed)

The lawsuit uncovered Caltrans reports as far back as 1985 that warned of the danger posed by the narrow shoulders and suggested narrowing the car lanes to leave more room for pedestrians. The idea was again raised in a 2016 report. For years, Helmer and other local transportation advocates lobbied for the idea.

“It was just mind boggling that so many things were brought to their attention,” Kelley Howard said. “It seems like things like that aren’t a concern until something horrific happens.”

She said she had never worried about her son’s walk to and from work, and had never walked the stretch of highway herself. About a year after his death, she drove up to the deli and followed his footsteps.

“It’s terrifying,” she said. “You actually feel the rush of cars going by. It’s just so close. But I still see people do it all the time.”

During the lawsuit over Josh Howard’s death, Caltrans’ lawyers argued that Shreves’ dangerous driving, not the highway design, was to blame. “Josh Howard himself may also bear some responsibility” for the crash by choosing not to walk on the side with a wider shoulder, Caltrans’ attorneys wrote in court documents.

In 2022, a jury in the civil case found that the stretch of Highway 9 created a “reasonably foreseeable risk” of pedestrian death that Caltrans failed to act on, and that Shreves had driven negligently. The jury ordered a $9.7 million payout — 49% from Caltrans and 51% from Shreves.

Kelley Howard never got the money from Shreves, which didn’t surprise her — it was obvious to her that he didn’t have money to give. With her portion of the payout from Caltrans, she bought her home in Scotts Valley. Soon after, she purchased another home two doors down for her aging mother, who could no longer drive and had been relying on the bus to travel from her Boulder Creek rental.

“She literally had to jet across Highway 9 to try to catch the bus going the correct way into town to Felton, which is just insanely dangerous because there’s no crosswalks either way,” she said.

Why progress is so slow

Highway 9 isn’t an outlier. All the state highways in Santa Cruz County are hotspots for cyclist and pedestrian crashes.

In 2008, state legislation pushed Caltrans to adopt a plan to include features like bike lanes and crosswalks on state highways. But nearly 20 years later, Highway 9, like many state highways, looks much the same.

Caltrans leaders fear that if engineers change a highway design and someone is injured, the agency will be sued, according to a 2014 assessment from the University of Wisconsin’s State Smart Transportation Initiative.

“It is easier for employees to either follow an established standard slavishly — or not to make a decision at all — than to creatively come to the best solution,” the audit stated.

“It’s not any one individual in Caltrans or group of individuals that’s holding us back necessarily,” said Brianna Goodman, an engineer with the Santa Cruz County Regional Transportation Commission. The commission works with Caltrans to undertake projects on local highways. “It’s more that there’s an accretion of layers that have been built over time to ensure that no one gets sued, to ensure that it’s the best use of public funds,” Goodman said.

Caltrans’ risk-averse mindset doesn’t consider that the decision not to build something new can also spark a lawsuit.

Now, Caltrans is working on something residents have requested for years: a sidewalk and expanded shoulder between Graham Hill Road and San Lorenzo Valley High. Construction is expected in the fall, and the sidewalk is expected to open in 2027.

A separate project is expected to bring new sidewalks, bike lanes and crosswalks to downtown Felton by 2029. Other safety improvements are planned for Main Street in Watsonville and Mission Street in the city of Santa Cruz, both state highways with high injury rates.

“I like their plans,” Howard said. “I think the time is what I have the most problem with.”

Caltrans and the transportation commission are now forming a plan for the next round of projects for Highway 9 and other rural highways in Santa Cruz County. At a May community meeting, an attendee asked why projects take so long. Caltrans Transportation Planner Paul Guirguis chose his words carefully.

“Because we’re responsible for billions of dollars, we also have to show that we’re responsibly using the money, which adds different processes, different milestones, checks and balances,” he said.

He looked to Goodman, his co-host and collaborator. “We’re all just doing our best within the system that has been constructed for us,” Goodman said. “But trust me, Paul and I are trying to move this along as quickly as humanly possible.”

Goodman is excited about the new sidewalks in Felton, and not just as a professional accomplishment. She hopes her 6-year-old daughter will one day use them to walk to school.

Building safer streets

A fifth-generation San Lorenzo Valley resident, Goodman, like Helmer, grew up in a much sleepier community, with a much quieter Highway 9. Her mom and aunt grew up in the 1970s, popping wheelies on dirt bikes in the middle of the highway, she said. The streets and buildings haven’t changed much since her own childhood in the 90s, but the traffic has increased.

Goodman disagrees with Helmer that narrowing car lanes would have made the highway safer. On a stretch with such heavy traffic, tight lanes could make cars risk a sideswipe from an oncoming logging truck, she said.

But she is sympathetic with his frustration about the long timelines for Caltrans projects. In the past six years, she said she has started to see improvements.

Like a barge trying to change course, “Caltrans is very slowly and ponderously making this huge swing from ‘We don’t want anything to get in the way of cars getting where they need to go as fast as possible,’ to acknowledging that there are many users and they have many different types of needs,” Goodman said.

Caltrans is in the process of updating the highway safety manual that guides its design decisions, and Goodman said she is optimistic that it will further improve the agency’s approach.

Dimitri Jaumouille shows a tattoo in memory of his son, Josh Howard.

(Marcello Hutchinson-Trujillo — Santa Cruz Local)

Those changes will come too late for Josh Howard. Six years after his death, his mother is still trying to find ways to move forward.

Before he died, he and his family lived in employee housing in Henry Cowell Redwoods State Park — a perk of his mom’s job as a park administrative officer. At least once a week, he walked to the Roaring Camp railyard next to the park and took the train through the redwoods or down to the Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk.

His sisters, now eight and 11, “still have arguments of who gets to sit next to Joshy on the ride. Like, pretending he’s sitting next to them, and we’ve got to leave space for him,” Howard said.

She used part of the settlement money to start a fund with Shared Adventures, a Santa Cruz-based nonprofit that helps people with disabilities participate in outdoor activities. Last year, it paid for 13 families with disabled children to ride the Roaring Camp holiday train with cars decked in lights. She and Jaumouille, Josh Howard’s father, rode along.

“I need something good to come out of all this,” she said, “to survive it.”

On a recent Wednesday afternoon, the two parents visited a redwood tree they planted for Josh shortly after his death. It was decorated with ornaments: Bowser, Sonic the Hedgehog, Spiderman. No longer a sapling, the tree towered several feet above them.

“I just love that it’s alive and it’s growing,” Kelley Howard said.

A mile away, the stretch of road where her son died bustled with cars and trucks and a few pedestrians skirted the shoulder.

Among them were Theresa Sapiens and Diana Patino-Geis, tenth graders at San Lorenzo High on their way to the Felton Branch Library.

“I usually take the back road because it’s so dangerous on Highway 9,” said Sapiens. “You’ve got to watch your back.”

But that day, they chose the more direct route to skip an extra mile of walking. Overgrown bushes blocked the narrow shoulder, forcing them across the white line as they continued down the highway.