Giving voice to families proves crucial in reporting on mental health conservatorships

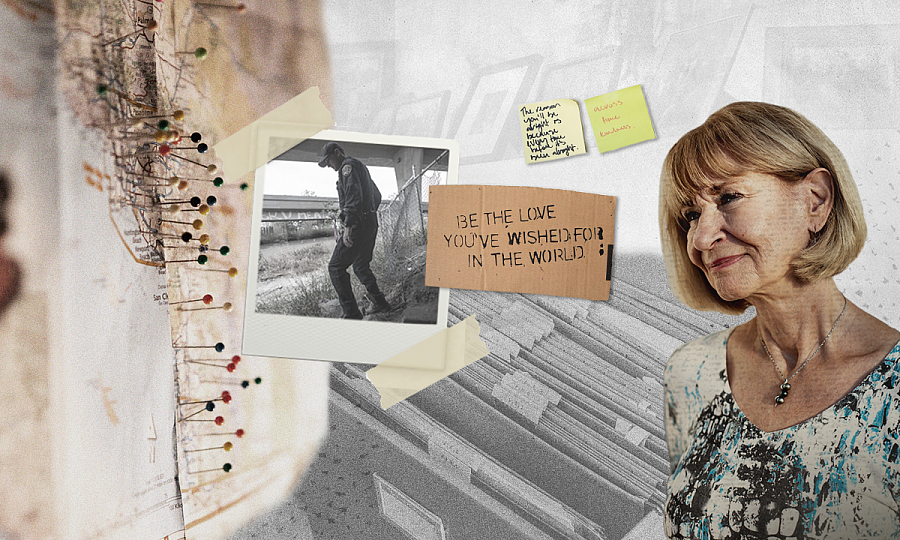

(Illustration by No Limit Creatives via inewsource)

The failures of California’s mental health conservatorship system were not particularly surprising. Inadequate resources and lack of state oversight meant there was plenty for a reporter to dig into.

But where to start — and how to narrow my project — was the difficult part.

With the help of the USC Center for Journalism California Fellowship, I spent months speaking with family members, advocates, health care professionals and law enforcement. In the end, I spoke with more than 40 people who gave invaluable input: They helped me drill down on which problems to focus on, shared their anecdotal frustrations that shaped our records requests and warned us of what previous news coverage got wrong.

But the most valuable lesson of those conversations was to lean into what prompted my interest in the first place: The lonely and seemingly never-ending struggle to get help for yourself — or someone you love, even if they don’t know they need it.

“It’s not the type of health crisis that you’re going to have neighbors come over and bring a casserole,” one advocate, Linda Mimms, told me.

Though I focused on San Diego and Imperial counties, our reporting revealed a lack of state oversight and woefully inadequate data across California. Even as some of San Diego’s most prominent leaders advocated for expansion, I kept hearing again and again this common frustration that decisionmakers were reluctant to seek conservatorships in some of the most complex cases — and thus, leaving out some of the most vulnerable residents. I found that data indeed showed that conservatorships were being pursued less often in San Diego.

I also reported that behavioral health officials in Imperial County were placing people under potentially illegal psychiatric holds despite prior warnings from consultants of possible civil rights violations.

I weaved that watchdog reporting with the voices of people with lived experience: People who had experienced psychiatric holds themselves, loved ones who endured crisis after crisis, even an elected official whose own family background influenced his position on mental health treatment. That effort made for some of the most powerful reporting in our series, and what resonated most with our readers.

Here are some lessons I learned.

Lean into community engagement.

Our efforts to reach people who would know the struggles of navigating the system firsthand was at the center of our reporting, and we sought ways to make our reporting helpful to them. Our community engagement helped us determine the first story to kick off our series: A dive into the efforts of two mothers who sought conservatorship for their adult sons.

We started with an off-the-record focus group to help shape our conversations and asked participants for recommendations on who else to speak with. From there, we embarked on more engagement:

We researched and compiled a list of support groups, individuals and organizations involved with conservatorships or mental illness. I sent personalized emails and messages and made phone calls clearly telling them my reporting goals and how I was hoping they could help. These conversations helped produce some of our richest sources, including those not specifically named in our reporting.

We accompanied a law enforcement officer who works on homeless outreach on a ride-along and spoke with residents about their experience with psychiatric holds.

We did an online callout seeking people who had experience with the system, and paid special attention to the language we used. That extra effort was successful – one mother who I spoke with as a result of that online callout said, “I felt like you were speaking to me.” We also relied on our media partners, and our callout was published in the Calexico Chronicle for our Imperial County readers. We garnered nearly 20 responses.

We created pull-tab flyers seeking even more possible sources and experiences, and posted them in locations we gave careful thought to — in libraries, areas where service providers were located and outside behavioral health buildings. Those flyers were created in both English and Spanish.

We designed a resource guide that will live on beyond our project, creating a central place for frequently asked questions and a flow chart that clearly lays out the conservatorship process. We envision this as a resource for people to seek answers if they want to know more about the process, as we found many who have loved ones with serious mental illness aren’t closely familiar, if at all, with conservatorships.

Make the unknown part of the story.

I embarked on this project hoping to answer this question: As conservatorships are being proposed for expansion in California, how are they currently working in our coverage area at inewsource? I quickly learned the question would be particularly difficult to answer. A major problem for mental health conservatorships is the lack of data, fueled by the multiple decision-makers involved in the process — and the absence of a statewide strategy and oversight to hold them accountable. I found that San Diego County couldn’t even provide historical data on the demographics of people on conservatorships, like race and ethnicity or housing status. We also found the vast majority of California counties weren’t tracking what are known as serial holds — back-to-back psychiatric holds that potentially violate state law. In fact, officials don’t fully know how many people are on a mental health conservatorship in California because the data collection is so shoddy.

So, I pivoted. I made that a core finding of our reporting: That expansion talks are happening while so little is known. We pointed out what exactly isn’t known, and why that matters.

Embrace the gray area.

Just because a project doesn’t deal with a black-and-white issue doesn’t mean it should be avoided. The mental health conservatorship system is an incredibly complex topic with a lot at stake. To place someone under a conservatorship is to place some of their most significant life decisions in the hands of someone else — where to live and whether to take medication, for example.

And yet some advocates and family members who spoke with inewsource said it’s the only possible option for recovery for some with a severe mental illness. One expert summed it up best for our reporting: “The conservatorship system can both be impossible to get into for some people who seem to really need it, and also have people stuck in it who don’t need it.”

Don’t shy away from that. The gray area is an important part of the story.