5 things to know: How polluted streams interact with the Memphis Sand aquifer

This story is part of a larger project led by Sarah Macaraeg, a 2019 Data Fellow who is investigating the disproportionate number of asthma diagnoses and severe symptoms among Memphis children.

Other stories by Sarah Macaraeg include:

To halt 'fast-track' Byhalia pipeline permit, Memphis groups file lawsuit in federal court

Near Byhalia pipeline planned connection point, Valero leaked 800 gallons of crude oil in 2020

Byhalia pipeline: Toxic refinery pollution, monitoring blind spot in southwest Memphis

Toxic air. Insufficient monitors. Why Memphis families fighting Byhalia pipeline have had enough

More than 100,000 people in Shelby County are facing a pandemic without health insurance

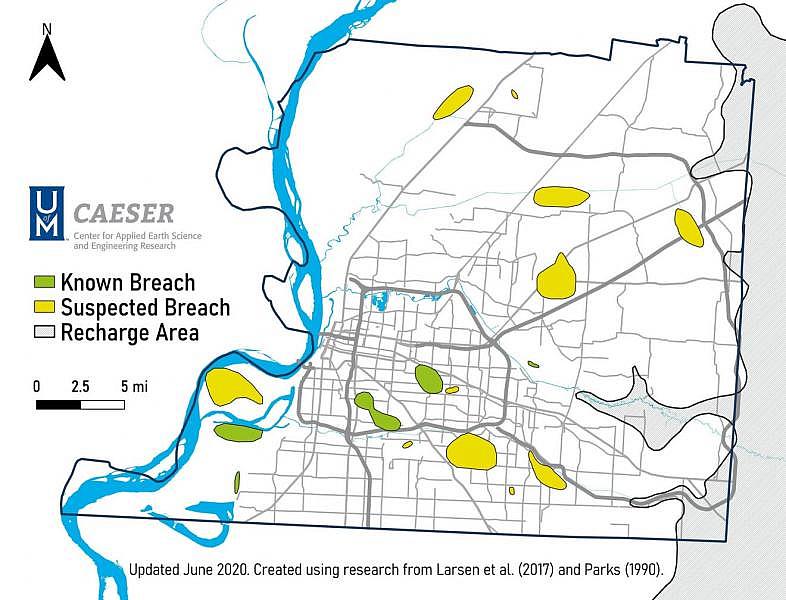

Known and suspected breaches in the Upper Claiborne Confining. Unit, identified by the Center for Applied Earth Science and Engineering Research of the University of Memphis. In the recharge area to the east, the confining clay layer terminates, leaving the Memphis Sand aquifer in direct contact with shallow groundwater. The deep drinking water aquifer, the Memphis Sand also interacts with shallow water at breaches, where the clay is thin or non-existent. Known breaches have been corroborated both in models and real-world geological investigations. Suspected breaches have been identified using modeling and are yet to be physically validated

Center For Applied Earth Science And Engineering Research

McKellar Lake: Taking a look back at what it once was, now polluted

Batsell Booker and Courtney Williams reminisce on McKellar Lake's past and how pollution took it away from swimmers, fishers and boaters. Ray Padilla, Memphis Commercial Appeal

Although it lies at least 250 feet below ground, the profile of the Memphis Sand aquifer exploded in recent months.

Amid debate over the now-canceled Byhalia crude oil pipeline, local residents and environmental justice luminaries around the country alike learned about the Mid-South's prized freshwater resource.

As wells run dry in Kansas; over-pumping draws saltwater into an aquifer in Louisiana and the Central Valley in California sinks as a result of groundwater extraction, the Memphis Sand remains abundant with trillions of gallons of hyper-purified water.

But it’s not impervious to contamination. As advocates continue to press for measures that would regulate future pipeline proposals, The Commercial Appeal found that scientists with the University of Memphis Center for Applied Earth Science and Engineering Research have been studying a new array of threats to drinking water quality.

In this July 2015 photo, water from the Memphis Sand aquifer sees daylight for the first time since being pumped from the deep below Memphis as it runs through a series of aerators to add oxygen back into the water and help remove carbon dioxide. Mike Brown/The Commercial Appeal

At least three streams seep water into the aquifer system

During certain months of the year, the Loosahatchie and Wolf rivers and Nonconnah Creek lose water to the shallow aquifer below ground.

“Streams give water to the aquifer at different rates, in different places, and at different times of the year,” said Brian Waldron, the director of CAESER who holds a doctorate in civil engineering.

“Even concrete culverts, or concrete channels throughout the city, have cracks in them,” he said. “Someway, somehow, there's a connection, usually.”

The shallow aquifer sits above the Memphis Sand, from which residents and businesses across Shelby County draw drinking water.

Known and suspected breaches in the Upper Claiborne Confining. Unit, identified by the Center for Applied Earth Science and Engineering Research of the University of Memphis. In the recharge area to the east, the confining clay layer terminates, leaving the Memphis Sand aquifer in direct contact with shallow groundwater. The deep drinking water aquifer, the Memphis Sand also interacts with shallow water at breaches, where the clay is thin or non-existent. Known breaches have been corroborated both in models and real-world geological investigations. Suspected breaches have been identified using modeling and are yet to be physically validated Center For Applied Earth Science And Engineering Research

“Short pass” from streams to drinking water

In at least 16 areas across Shelby County, a layer of clay above the drinking water aquifer is known or suspected to be thin or non-existent, allowing the drinking water supply to mix with more readily contaminated shallow groundwater above.

Municipal wellfields and other withdrawals pumped from the Memphis Sand aquifer serve to further draw in shallow groundwater, said Waldron, who declined to discuss the specifics of research involving the Loosahatchie and Wolf rivers and Nonconnah Creek.

MLGW bars scientists from freely discussing research findings

Under the terms of a contract stipulated by Memphis Light, Gas and Water, the research regarding stream-aquifer interactions has gone undisclosed to the public as of Aug. 8, in the third year of MLGW’s five-year, $5 million study of threats to drinking water quality, funded by customers via an 18-cent per month rate increase.

MLGW said it requires approval of communications to ensure accuracy and that planning for a public presentation was underway. The agency did not respond to a follow-up question to provide dates.

A sign at Martin Luther King, Jr. Riverside Park Marina at Lake McKellar in Memphis warns against consuming fish contaminated with carcinogens. Sarah Macaraeg/Commercial Appeal

Industrial facilities discharge toxic waste into streams

Of more than 460,000 estimated pounds of toxic pollution Shelby County facilities reported releasing to water, according to Environmental Protection Agency data, the vast majority by volume was released in southwest Memphis. By EPA risk-score, which takes differences in chemical toxicities and other variables into account, the stormwater runoff of a facility in Millington, Kopper’s Performance Chemicals, ranked highest. A company spokesperson said Koppers was “committed to the safety of its employees, communities and environment” and noted that it holds valid permits.

New details regarding Valero and TVA operations emerge

National Response Center call logs show the frequency of hazardous materials releases in Memphis, which inspired a former National Fire Academy instructor and Hazardous Materials specialist to profile the city given its “many unique hazmat exposures”. The Valero Memphis oil refinery, whose representatives have voiced opposition to efforts aiming to regulate infrastructure which could impact the aquifer, is among local facilities which appear repeatedly in the data.

Valero did not respond to requests for comment and has previously stated it does not comment on operations as a matter of company policy.

Regarding Horn Lake Cut Off, a waterway which runs proximate to drinking water wells in Boxtown and the subject of recent controversy after a sample taken by CAESER showed arsenic at four parts per billion: A spokesperson for the Tennessee Valley Authority, which is mitigating neighboring coal ash ponds, said the facility’s connection to Horn Lake Cut Off, specified in a renewed Tennessee Dept. Of Environment and Conservation permit, is indirect.

TVA Allen Fossil Plant seen across McKellar Lake on Thursday, Oct. 1, 2020. The coal plant, which closed in 2018, is likely responsible for much of the carbon Memphis put in the atmosphere over the last six decades. Joe Rondone/The Commercial Appeal

At a June MLGW Board of Commissioners meeting, a TVA official said, “Surface water runoff from Allen does not go to the Horn Lake Cut Off.”

Upon follow-up, a spokesperson said TVA used Horn Lake Cut Off as an emergency outfall from April 5 to May 7 in 2004, with TDEC’s approval.

“All water streams at the site are managed and permitted as required,” said Cedric Adams, the principal project manager of the Allen Fossil Plant.

Sarah Macaraeg is a former Commercial Appeal journalist who commenced her reporting on environmental health in Memphis as a USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism Data Fellow. Currently based in Chicago, she can be reached on Twitter @seramak.

[This story was originally published by Commercial Appeal.]