Being outside can be dangerous, especially at school

This story was made possible with support from the Center for Health Journalism at The University of Southern California.

Other stories in the series include:

The danger of urban ‘heat islands’

How Hot Was It In California Homes Last Summer? Really Hot. Here's the Data

Investigation Finds Home Can Be the Most Dangerous Place in a Heat Wave

Extreme Heat Killed 14 People in the Bay Area Last Year. 11 Takeaways From Our Investigation

Even in San Francisco, Heat Is Turning Deadly. That's Not Something Colleen Loughman Expected.

It's getting (dangerously) hot in Herre

Sweltering in nursing home, 95-year-old succumbs to heat, as climate endangers most vulnerable

What you need to know about LA’s urban heat problem

New Rule Would Require Employers to Protect Indoor Workers From Heat Illness

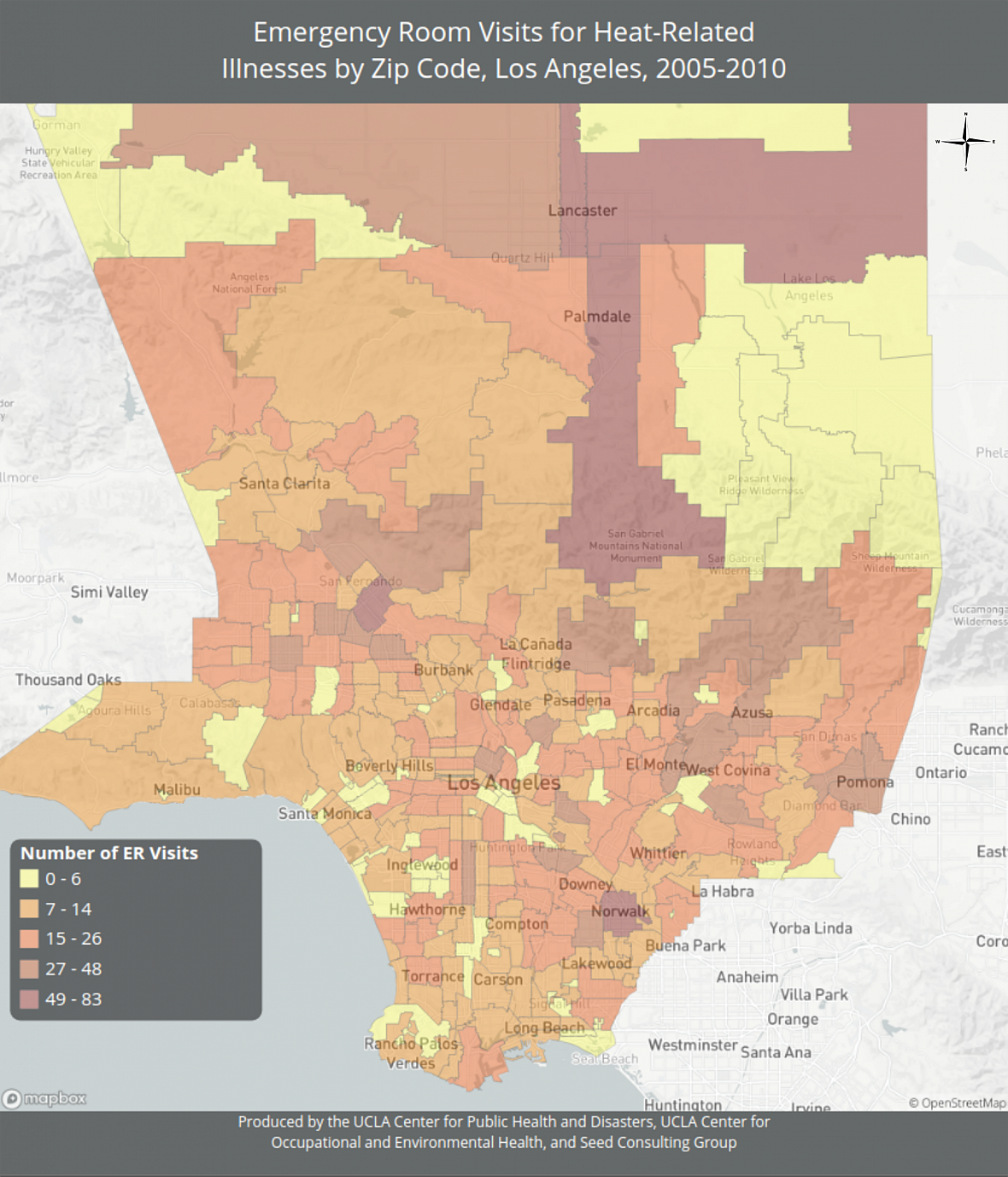

Produced by David Eisenman and Holly Wilhalme with the UCLA Center for Public Health and Disasters, Michael Jerrett and Jonah Lipsitt with the UCLA Center for Occupational and Environmental Health, and Noah Olsman and Sam Squires with Seed Insights and Seed Consulting Group.

Being outside can be dangerous, especially at school

Every year kids go back to school during Southern California's hottest months. Temperatures can reach over 100 degrees. Some students spend their days in air conditioning, but others are not so lucky. And those hot classrooms can impact kids' ability to learn.

Kids get hot on the playground. “The simple fact that a child’s core is closer to the ground because they’re shorter puts them at greater risk,” says Jenni Vanos, a Scripps Institute scientist who studies how climate affects human health.

Many school districts develop policies to cope with heat outdoors. The Los Angeles Unified School District starts limiting outdoor activity when the heat index hits 91 degrees.

Where kids play – grass and asphalt, bouncy rubber or artificial turf – changes heat exposure. With synthetic surfaces, Vanos says, “We’re making little micro-climates that are almost like tiny little heat islands within the heat island of the greater urban area.” So shade is important. Schools like Telfair Elementary, deep in the San Fernando Valley bring out extra canopies and tents when it gets too hot.

Budgets for cooling classrooms are on the rise

Harvard environmental economist Jisung Park has found that students taking a test when it’s a sweltering 90 degrees out are 12 percent more likely to fail compared to students taking a test when it’s a balmy 72. “Even these short periods of heat exposure can have really long lasting, maybe even permanent, educational and economic consequences,” he says.

Bond money and ballot initiatives drive classroom upgrades. So Long Beach is on its way to fully air conditioning its classrooms. In Orange County, Newport-Mesa Unified School District is not; the teachers’ union there has an open grievance against the district over air conditioning, after a heat wave caused teachers and students to get sick in 2015.

Los Angeles is one of the largest school districts in the nation with air conditioning in 100% of its 30,000-plus classrooms. Keeping that A/C humming isn’t easy. “When school starts, and we have occupants in all these classrooms and all the air conditioning systems are running and temperatures are at their hottest, the backlog can jump into the thousands,” says Roger Finstead, the Los Angeles Unified School District’s Director of Maintenance and Operations. “Real fast.”

Heat can be dangerous all year long

Urban heat kills people, even after Halloween. “There are these beautiful, around the holidays, Christmas time, days in southern California, where it suddenly hits 80 degrees, and you’re driving in your convertible thinking, my gosh, it’s beautiful to live in Los Angeles in the winter, how lucky am I,” says UCLA professor of medicine David Eisenman. “It’s on those days, those unusually warm days in the winter, that these winter extreme heat days lead to extra deaths.”