In booming Philadelphia neighborhoods, lead-poisoned soil is resurfacing

This story was originally published in The Inquirer with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

Jana Curtis and two of her children walk past one of many construction sites in their river ward neighborhood. Three-year-old Nolyn Pace, center, was poisoned by lead in the soil in their backyard.

By Wendy Ruderman, Barbara Laker, and Dylan Purcell

Her Kensington neighborhood is full of charm. Swank cafes with rustic wood and vintage lighting. Stoops and decks with skyline views. Young parents who bond at parks while their children play.

Jana Curtis, a mother of three, finds excitement in this urban renaissance.

But with it comes a sad reality.

Her daughter was poisoned by lead. The culprit wasn’t paint. Or tap water. But soil — in her own backyard.

“The yard was poisoning my daughter,” Curtis said. “It’s just so horrifying.”

Curtis and her family live in the heart of what was once Philadelphia’s industrial hub. For most of the last century, the “river ward” neighborhoods of Fishtown, Kensington, and Port Richmond, which snake along the Delaware, were blanketed with hulking factories and lead smelters. It was a time when manufacturers used lead in everything from paints to plastics. Lunch-pail laborers walked to work from tightly packed row homes as lead dust spewed from smokestacks, coating sidewalks, stoops, and yards.

Once in the soil, the heavy metal stays indefinitely. Even minuscule amounts can permanently lower a child’s IQ and cause behavioral problems.

At one time, Philadelphia had 36 lead smelters — more than any other city in America. Fourteen alone operated in these river wards.

The lead plants are long gone, either razed or shuttered. But their toxic legacy remains.

Today a development boom is disturbing lead that has sat dormant for decades. Construction crews — unchecked by government — churn up poisonous soil that can spread toxic dust across these gentrifying neighborhoods. This renaissance puts a new generation of children at risk.

In the area’s most sweeping environmental investigation to date, the Inquirer and Daily News tested exposed soil in 114 locations in the river wards — parks, playgrounds, yards. Nearly three out of four had hazardous levels of lead contamination — a problem of previously unknown severity.

Melissa Billingsley, a state-licensed risk assessor for Criterion Laboratories, takes a soil sample in a yard located on the 2600 block of East Thompson street. The yard tested high for lead.

In addition, reporters discovered high levels of lead dust on rowhouse stoops and sidewalks near construction sites. In tests taken from a popular neighborhood playground — both before and after digging began at a vacant lot across the street — a once-safe play area was shown to contain lead dust.

Developers are not required to test soil for lead as a routine precaution before disturbing land. Further, no single governmental agency is responsible for making certain a yard’s soil is safe.

Federal, state, and city officials, who have known about lead in the soil here for decades, quibble over who, if anyone, should regulate development within a former industrial area. State and federal officials say they only oversee development and cleanup within the boundaries of known contaminated sites. City officials say they don’t regulate soil.

The city’s Department of Public Health is supposed to enforce a regulation that requires construction crews to contain noxious dust. Reporters spent five months in these neighborhoods, testing soil, interviewing residents, and keeping tabs on at least two dozen ongoing construction sites. Not once did they see workers take dust-control measures, even something as simple as spraying water to hold down dust.

Philadelphia Health Commissioner Thomas Farley said the city enforces dust regulations “to the extent that we can.”

Farley pointed out that lead paint — not soil — is the primary source of childhood lead poisoning. “Lead levels correlate to poverty and they correlate with older housing,” he said. “They don’t light up where there were smelters.”

Farley said that while parents should try to prevent their children from playing in dirt in these neighborhoods, he doesn’t consider soil a major risk. “Risk from soil and dust is — it’s certainly a theoretical risk.”

Experts such as Mary Jean Brown, former chief of lead-poisoning prevention at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, strongly disagree.

Brown has long studied the health impacts of lead-laced soil on young children and pregnant women in these postindustrial neighborhoods. There are dangerous levels of lead in the soil here, so we must do something, she said.

The wave of new construction only adds to the peril, Brown said.

“When they’re digging it up and it’s fine enough to be inhaled, then it’s a big issue,” she said. “We can’t ignore this.”

WHERE WE FOUND UNSAFE LEVELS OF LEAD

Fourteen smelters in the “river wards” once spewed toxic lead over the Fishtown, Kensington and Port Richmond neighborhoods. In the first comprehensive analysis, the newspaper tested the soil for lead in 114 locations, including parks and playgrounds. Three out of four had hazardous levels. One backyard tested nearly 25 times the acceptable limit.

Lead in the soil is measured in parts-per-million (ppm). Parents are advised to keep children from playing in soil above 400 ppm.

‘INHALATION IS WORSE’

Jenni Drozdek and Dan Morgan knew all about the neighborhood’s toxic legacy when they moved into their home on Cumberland Street in Kensington in 2011.

They even had their soil tested before planting a garden where they wanted to grow kale, tomatoes, beets, and carrots.

Federal guidance says not to grow root vegetables or allow children in gardens where soil tests above 150 parts per million (ppm).

An EPA-funded experiment of vegetables grown in Kensington soil with lead at roughly 1,000 ppm found carrots and beets with lead at five to 40 times the safe level for human consumption.

The result of the couple's soil test came back at 662 parts per million, considerably higher than the federal threshold. The EPA considers hazardous any lead concentration above 400 ppm in soil where children play.

The couple installed raised beds filled with new topsoil. They also spread a thick, protective layer of mulch over the rest of the yard.

Mina plays with dirt in the raised garden beds in her backyard. Mina's mother, Jenni Drozdek, is an avid gardener and installed raised beds with fresh soil in their Kensington backyard to avoid contaminants in the ground soil. Despite that precaution, Mina developed lead poisoning.

When their daughter, Mina, was born three years later, they thought she would be safe.

Then construction fever heated up.

All around them, demolition crews worked at a frenzied pace. The buzz of saws and the beep-beep of excavators backing up could be heard on almost every block. In their 19125 zip code, the number of demolitions doubled between 2015 and 2016. Construction projects increased fivefold since 2010.

The mammoth reconstruction of I-95 nearby also added to the dust bowl.

The grit made residents’ eyes water. And there were days when Drozdek found her gray Nissan blanketed in dust.

“I had to clean it off because I couldn’t see out the windows,” she said.

Last August, the city’s health department adopted more stringent dust-control regulations. But some 30 Fishtown and Kensington residents interviewed in the last few months said they never witnessed a construction project with dust controls.

“There’s no effort to contain it whatsoever,” Drozdek said.

The couple often take Mina to one of the busiest parks in Fishtown, Shissler Recreation Center on Blair Street. It was once the site of a major railroad hub and train yard.

Earlier this year, a reporter took a dust-wipe sample from the playground and found no detectable levels of lead.

About three months later, in early May, a reporter took another sample from the same spot. At the time, construction workers were using backhoes to dig foundations for new homes going up across the street. Dust and dirt were swirling around as children were busy at play.

This sample shot up to 127.4 micrograms of lead in dust per square foot. While there is no federal hazard level for outdoor surfaces, the limit for entryways and indoor floors is 10 and 40 for porches.

Whether the lead came from a construction site across the street is uncertain.

When construction manager Justin Kaplan was told that tests revealed high lead levels on playground surfaces, including where children had scrawled chalk drawings, he said he felt sick.

“I have kids,” Kaplan said, his voice anguished. “I don’t want my kids rolling around in lead dust while they are chalk-drawing — believe me.”

After his crews unearthed old storage tanks during excavation, they had to stop and have the soil tested, he said. It came back high for lead, he said.

Montgomery County developer Nicholas Sylvestro, of the La Capretto company, is building six single-family homes on the Blair Street site. He did not return three calls seeking comment.

Exposure to contaminated soil and demolition debris containing lead paint can significantly increase blood lead levels in children, studies show.

A child who inhales lead dust faces more danger than one who swallows dirt because dust has a more direct path to the brain, experts say.

“Ingestion is bad,” said Richard Pepino, an environmental toxicology expert at the University of Pennsylvania.

“Inhalation is worse.”

Simple dust-control measures can prevent people from being harmed, but the health Department has only four air management inspectors and two supervisors to oversee a city that last year alone had about 2,500 demolition and construction jobs.

When Drozdek and Morgan took Mina to her routine one-year checkup, her bloodwork came back with a poisonous level of lead: 9 micrograms per deciliter.

The CDC says public health and pediatricians should intervene when children have a blood lead level of 5. At that level, children lose six IQ points on average. Even with lower lead levels, children exhibit increased impulsivity, aggression, and hyperactivity, and have diminished academic abilities, research shows. In adults, experts say, low-level exposure over time can cause memory loss and depression, and harm the heart, kidneys, brain, and reproductive functions.

For now, the Health Department investigates only when a child hits a level of 10. Drozdek’s daughter is among roughly 2,000 city children every year who spike a blood lead level between 5 and 10 and whose families are left to fend for themselves.

“I was terrified because you hear how lead poisoning and any kind of lead levels can be dangerous,” Drozdek said.

Drozdek bought kits to detect lead on painted surfaces and tested all over her house. That wasn’t the source. The couple had their water tested. They ruled that out, too.

“It was definitely coming from the outside,” Morgan concluded. But where exactly?

Drozdek and Morgan invited reporters to retest their yard. At the time, a giant excavator clawed into a large vacant lot on Letterly Street directly behind their house. Digging had gone on for days, creating a hole roughly the size of an Olympic swimming pool.

Construction crews had dumped excess soil on an adjacent city-owned lot. Reporters sampled the soil and found high lead – 1,647 ppm.

Jenni Drozdek and her daughter, Mina, in the backyard at their Kensington home in Philadelphia, where new homes are being built directly behind theirs.

Developer Steven Kravets, of Bucks County, said he did not test the soil for lead beforehand. He said it wasn’t required. The city does require developers to do a geological soil survey to make sure the land is firm enough to support a large structure.

“For that area, a quick study by the soil engineer. There was not much to it,” Kravets said.

When told about the lead in the dirt pile, Kravets asked if reporters had tested soil not just in Kensington, but in neighboring Fishtown. Told yes, he offered no further response.

There are tall piles of dirt at construction sites all over both neighborhoods.

Down the street from Drozdek’s house, a work crew heaped dirt and rubble into 8-foot-high piles.

THE CONSTRUCTION BOOM

The river wards' continued revival has added swank cafes and spruced-up parks to this former industrial neighborhood north of Center City. Its newfound appeal can be seen in the surge of construction and demolition permits as builders race to meet demand for new homes nearly unmatched in Philadelphia. Building fever has also disturbed contaminated soil, sending hazardous lead dust onto playgrounds and stoops.

“There are mounds of it and children climb on it and play on it,” Drozdek said. “Then of course when it’s windy, the top layer gets blown all over the streets.”

Two soil samples from her backyard tested high for lead — 635 and 726 ppm.

Reporters also swipe-tested for lead dust on their front steps. It came back at 1,760 micrograms, 44 times higher than the residential limit for porches.

When told the result, Drozdek was speechless, realizing that Mina had spent hours on the stoop.

“She would grab the steps and pivot herself to the next one,” Drozdek said. “Of course, she’s a little kid, so she’s putting her hands in her mouth.”

Mina’s blood lead level is lower now. Every day, the couple give her iron drops to prevent lead from binding to her bones. They clean religiously, even wiping down stroller wheels.

Still, as the construction boom continues, they wonder if it’s enough.

SHE SPOKE ONLY TWO WORDS

John Zippert and his wife, Carol. John works with the farmers cooperative that connected Peterson with Greene County Hospital.

It has almost become routine. Jana Curtis finds herself pushing her baby stroller through her Kensington neighborhood, her three kids in tow, when suddenly she freezes. The minute she sees construction machinery digging up dirt, sending plumes of potentially hazardous dust into the air, Curtis abruptly zooms across the street to avoid any danger.

“It’s always on my mind,” she said.

She sweeps the front steps of her York Street home regularly. There are no shoes allowed in the house, so sneakers and sandals are neatly lined up at the front door. She vacuums twice a day and mops once.

She misses her two dogs who passed away, but won’t adopt another. A dog would track toxic dirt into the house. “It’s not worth it with them going outside and coming back in,” she said. “It’s their paws. I can’t take their shoes off.”

If one of her kids drops a piece of food on the ground, there’s no “five-second rule.”

“I scream, ‘No! You can’t touch it!’ We look like crazy people,” she said.

She has good reason to be hypervigilant. Three years ago, the CDC tested her tap water and backyard soil as part of a lead study in the neighborhood.

She was stunned by the results. Her house and water were safe. But she said her yard tested at 1,100 ppm — nearly three times the federal limit.

Curtis rushed her daughter, Nolyn, 11 months old at the time, to her pediatrician for a blood test. She had a lead level of 14 micrograms per deciliter, almost three times higher than the amount that the CDC considers troubling.

“It was heartbreaking,” Curtis said.

At 18 months, Nolyn spoke only two words. Curtis’ oldest child at the same age had a vocabulary of 70.

Curtis, and her husband, William Pace, a physician who specializes in infectious diseases, enrolled Nolyn in speech therapy and played educational games with her. Now 3, Nolyn took big leaps in speech but “still has pretty significant behavioral challenges,” Curtis said.

Her daughter struggles to make simple decisions, which can trigger temper tantrums.

So Curtis eliminates choices. “There’s only one sippy cup for her because every morning there was this big battle. She can’t even make a choice between two so we only have one kind. There’s no choice. There’s only one pair of shoes. One coat. One cup.”

At times, guilt still plagues Curtis. “Maybe if I’d cleaned more, she wouldn’t have gotten this. Maybe if I had mopped every day, she’d be fine,” she said, her voice cracking.

Still, there’s only so much that brooms and sanitizers can do, she said.

“We’re not going to clean our way out of this problem,” Curtis said. “I can clean up enough to protect, Graham, my littlest. But you can’t clean your way out of this toxic-ness that’s coming from all these different places. There’s got to be a bigger solution than what I can do in my four walls. It just can’t be about mopping.”

STAY OFF THE HILL

Longtime residents like Gregory Antczak thought they had found something of a solution to their neighborhood’s toxic legacy more than a generation ago. Now they know differently.

Antczak grew up in the shadow of the area’s most notorious lead factory, an eight-acre complex of 52 buildings and nine smokestacks sprawled along both sides of Aramingo Avenue. Over nearly 150 years, workers ground lead into a powder used in bathtub enamel, paint, soaps, car batteries, and plastics. Residents knew the behemoth by different names. John T. Lewis Brothers. Dutch Boy Paint. National Lead. And finally, Anzon.

“They always did the same thing,” said Antczak, 68, of the companies. “They processed millions and millions of pounds of lead in the middle of a highly populated residential neighborhood.”

As a boy, he had to take part in routine family evacuations. “A siren would go off inside the factory. It was like an air-raid siren, shrill and high,” he said. The sound signaled a fire, chemical spill, or some other peril.

His dad would utter the same four words: “Get in the car.”

Antczak and his older brother would hop into the family’s two-tone 1950 Ford — white roof, salmon-colored body — as black smoke and a noxious smell filled the air. His dad drove eight miles north to the house of Antczak’s aunt.

“It was the same thing all the time,” Antczak said. “We get there, the coffeepot would go on the stove, the cake would come out of the refrigerator, and then we’d wait it out.”

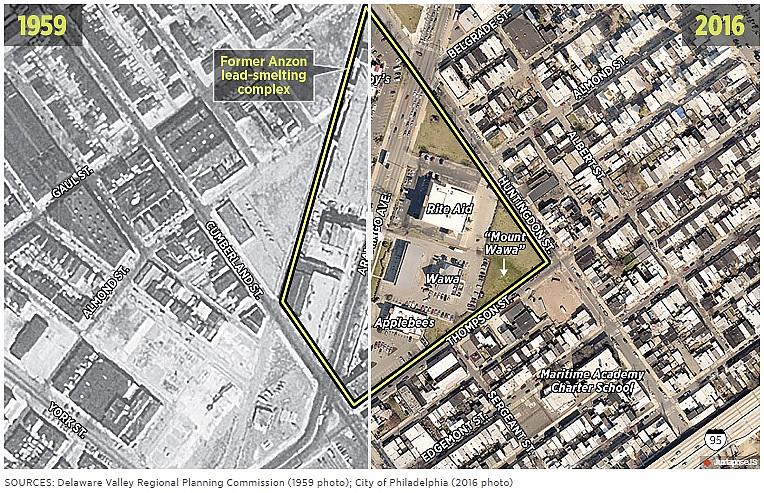

ANZON, BEFORE AND AFTER

Demolition of the eight-acre Anzon factory, the area's most notorious lead-smelting complex, began in 1999. The former brownfield is now an asphalt-covered retail hub. The developer was allowed to cap a toxic mound with a foot or more of clean fill dirt and plant grass, which residents dub ”Mount Wawa.“ Reporters who tested the soil at the base of the mound found lead levels six times the allowable limit.

The images below show the Anzon site in 1959, when it was in operation, and in 2016. Use the slider to compare the two images.

Staff Graphic

The family had a puppy, a black mutt named Eliza Jane. At only a year old, the dog had a distended stomach and couldn’t stop vomiting. Their beloved pet died from what the vet called “lead belly,” Antczak said.

In the early 1980s, Antczak got married and bought a house near his parents about a block from the plant.

A few years later, a plant fire blasted out so much lead dust that Anzon evacuated the surrounding blocks. It took Anzon three days to vacuum streets and sidewalks, and decontaminate homes, inside and out.

By then, Antczak and other nearby residents had had enough. They sued Anzon in 1987 for contaminating their homes and imperiling their children. Years later, they settled with the company.

Most families received a few thousand dollars. The largest payout was $16,000. Some families used some of the money to pave over their backyards with concrete to encapsulate the toxic soil.

Anzon began demolishing the plant in 1997, leaving behind a wasteland of rubble and a mound of dirt near the intersection of Thompson and Huntingdon Streets.

A private company, Port Richmond Development, purchased the land. Under a program to develop brownfields, the state Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) gave the developer liability protection in exchange for complete cleanup.

The former brownfield is now an asphalt-covered retail hub with an Applebee’s, Dunkin’ Donuts, Rite Aid, AutoZone, and Wawa. Rather than hauling away the toxic mound, the developer was allowed to cap it with a foot or more of clean dirt and plant grass. Residents have dubbed the mound “Mount Wawa.” Many cringe when they see children playing on it.

As part of its agreement with the DEP, the developer is required to have an environmental company routinely inspect the hill and surrounding asphalt.

The task involves little more than looking at it.

An inspection log for the site from 2004 to 2012 shows that an inspector wrote the same two sentences for the nine consecutive visits: “All asphalt perfect condition. All grass and landscaping perfectly in place.”

The state does not require the developer to test the mound for lead.

Meanwhile, residents have had their doubts. In a 2012 investigation of former lead smelters nationwide, USA Today found high lead levels in soil near Anzon. Some residents urged the EPA to determine whether Mount Wawa was safe. The developer’s environmental firm gave an answer:

“We are pleased to report, as expected, that the cap is being appropriately maintained, and remains protective.”

Reporters recently tested a patch of bare soil at the apron of Mount Wawa. Its lead level came back at 2,904 ppm, more than seven times the allowable limit for areas where children play.

“We were told it was safe, that it was all encapsulated,” said Sandy Salzman, former executive director of the New Kensington Community Development Corp. This news brought fresh worry.

“In the summertime, the kids play there and slide down the hill,” Saltzman said.

Told that Mount Wawa tested high for lead, DEP Secretary Patrick McDonnell said: “It’s something I’d want to hop on.” The agency will check it out, he said.

Neal Rodin, president of Port Richmond Development, said people should stay off the hill — period.

“Children are not supposed to play on it. It’s a commercial site,” Rodin said. “It’s good you’re doing the story. Hopefully, parents will know then to keep their children away.”

Just across the street from the old Anzon site is Cione Playground, which decades ago had been saturated with lead. In a one-time arrangement, the city received $500,000 from the company in the late 1990s to abate the lead and, under EPA guidance, make the playground safe.

Reporters recently tested soil at Cione’s ball fields, and it came back low. But soil tested in four locations near the community swimming pool returned unsafe levels, between 613 and 955 ppm.

Told of the test results, city spokeswoman Lauren Hitt said the city was not responsible for regulating soil. “If we become aware of a toxic soil situation, we notify EPA and/or DEP,” she replied in an email. “If there is an immediate health threat, we will, of course, also try to use our general police powers” to protect the public.

THE ‘SILO PROBLEM’

Brown, the former CDC lead expert who now teaches at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, put it in blunt terms: “Everybody’s problem is nobody’s problem,” she told a group of peers at an EPA workshop last year in Philadelphia on lead hazards in urban soil.

All neighborhoods near former lead smelters are likely to have unsafe levels of lead in the soil, the experts noted. Most everyone in the room agreed that tackling the problem requires urgency. But not everyone could agree on a solution — or which agency should take charge.

Brown has grown weary of the hand-wringing and often fruitless quests to find the responsible culprit from years past.

“How did it get in the soil? That train has already left the station,” Brown said in a recent interview. “We know it’s there. We know how to fix it. Now let’s fix it.”

PHILADELPHIA'S INDUSTRIAL LEGACY

Philadelphia, once known as the “World’s Workshop,” churned out everything from toys to textiles. For more than a century its factories, many clustered along the Delaware river, brought jobs and prosperity – and pollution. With 36 smelters, Philadelphia had more than any U.S. city. If left undisturbed, toxic lead dust spewed from smokestacks can remain in the soil for hundreds of years.

Government should not use little kids as walking test tubes, tackling lead hot spots only after little kids suffer neurological damage, she said. The best way to protect them is to remove all the toxic soil, she said.

It sounds so simple. But is it?

Reporters shared their test results with the state DEP, including one for a Fishtown backyard that came back at 9,883 ppm. Patrick McDonnell, the agency’s secretary, replied: “Any time we see sample results like this, it’s definitely cause for concern,” McDonnell said last week.

The state has laws to hold polluters accountable. But as it stands now, the DEP has no regulatory power to remedy what McDonnell calls widespread “historic pollution or contamination.” McDonnell, who was confirmed by the Senate last month, said he is still trying to determine whether the state has any authority to require developers to test soil for lead before disturbing land adjacent to known brownfield parcels.

As for the 82 of 114 properties that tested above 400 ppm for lead, he said: “We’d need to look at specific sites and where our regulatory authorities are. Can we figure out the source of the contamination? Are there still viable responsible parties?”

“We absolutely want to engage and understand the extent of” the problem, McDonnell said.

So does Jack Kelly, an EPA official based here. Kelly has been alerting higher-ups for years about the lead problems in Fishtown, Kensington, and Port Richmond. In a perfect world, residents all over the area would allow him to test their soil and he could map the boundaries of the contamination and make a case to his bosses that backyards in this area should qualify for federal cleanup money.

In the meantime, Kelly has persuaded the EPA, as a public service, to take the unusual step of contracting with a phlebotomist to test the blood lead levels in children, ages 6 and under, who live in the river wards.

The EPA is still working out the details but hopes to begin testing this summer. During a community meeting earlier this year, residents like Jana Curtis, whose child was poisoned by soil, broached the elephant in the room: “Is there any danger of this money disappearing, given the current political climate?”

Kelly struggled to answer the question, knowing that the Trump administration has proposed slashing the EPA’s budget by nearly one-third, more than any other agency.

Jill Replogle

“This is, not compared to a lot of work we do, a big-ticket item,” Kelly told Curtis. “I don’t think we’re going to lose the money for this.”

David C. Bellinger, a professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, is tired of inertia. He and fellow clinicians and scientists recently formed Project TENDR(Targeting Environmental Neurodevelopment Risks). Last month, the group, in the medical journal JAMA Pediatrics, called for “remediation of lead-contaminated soils from former industrial sites in residential areas” and for “federal, state and local governments to provide a dedicated funding steam to identify and eliminate sources of lead exposure.”

Bellinger said the findings by reporters that high levels of lead lurk in the soil in these neighborhoods, coupled with the lack of government oversight and controls, illustrate what he calls “the silo problem” — each agency focuses on “a narrow aspect of the problem without any integrated effort to stitch all the pieces together.”

Bellinger’s coalition is calling for swift national action. “Further delay,” it warns, “will result in more children experiencing lifelong health problems.”