California needs more Latinx therapists — but the mental health field is still full of barriers to entry

This story was originally published in KQED with support from the 2022 California Fellowship.

Despite growing demand for mental health services for children, the mental health field has failed at recruiting enough professionals of any background. California has less than a quarter of the therapists it needs — and the existing workforce doesn't mirror the state's demographics, making culturally competent care difficult to come by.

(Illustration by Anna Vignet/KQED)

Growing up in Daly City, Eric Valladares remembers hearing how his parents and extended family fled El Salvador during the country’s 12-year civil war that ended in 1992.

After settling in California, some members struggled financially, finding it hard to adjust to a country where they didn’t speak the language and felt like outsiders.

His family never discussed how they coped with those traumas or mentioned mental health. He remembers adults masking emotions with alcohol, something he later imitated. He didn’t realize he had a problem until he was in graduate school, learning how to help others with their problems.

Valladares decided to become a therapist while an undergraduate student at San Francisco State University. He made the career choice believing he just wanted to help the Latinx community, but his decision was deeper than that.

“There was pain and there were experiences from my life and my family’s life that in subtle ways put me on this path,” he said. “I wanted to help others heal and help myself heal, but it didn’t occur to me until later. I thought of it as, ‘Isn’t it nice that I want to help people?’ But no, it was really, ‘I have unresolved issues and I want to work them out.’”

Valladares, now 37, spent years providing therapy to mostly immigrant, Spanish-speaking people. He’s now the executive director of Family Connections, a Palo Alto nonprofit that provides educational and mental health services to families with young children.

Executive Director Eric Valladares at the Redwood City location of his mental health nonprofit, Family Connections. (Beth LaBerge/KQED)

In many ways, Valladares exemplifies what experts and policymakers say California needs more of: He's a multilingual Latino who brings cultural competency to mental health services. But his journey into the profession demonstrates the difficulties mental health care providers face, such as addressing their own traumas and figuring out how to navigate the professional mental health field — from earning enough money to dealing with insurance companies resistant to paying for patient care.

'Folks need to be served by people who look like them'

Despite growing demand for mental health services for children struggling with depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation, the mental health field has failed at recruiting enough professionals — of any background. California has less than a quarter of the therapists it needs to care for the state’s population, and the majority specialize in treating adults, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

And the existing mental health workforce doesn’t mirror the state’s demographics. About 40% of Californians identify as Hispanic or Latino, according to research provided to KQED by the Healthforce Center at UCSF. But only 9% of clinical psychologists, 21% of marriage and family therapists and 27% of mental health counselors identified as Hispanic or Latino from 2015 to 2019, the research shows.

“Part of what makes any kind of therapeutic intervention work is the relationship between the provider and the person getting the service,” said Chris Stoner-Mertz, CEO of the California Alliance of Child and Family Services, a coalition of about 150 nonprofits and organizations that serve the state’s children and families. “Folks need to be served by people who look like them and who maybe had some of their life experiences.”

The two biggest barriers to accessing mental health care are the cost and lack of providers. Insurers make it difficult for therapists to get paid by requiring a lot of paperwork, limiting mental health services they will cover and covering only patients with specific diagnoses or those who meet “medical necessity.”

Mental health professionals tend to fall into two camps: those who work in the public or nonprofit side and those in private practice. To avoid the hassle of dealing with insurance companies, many therapists go into private practice and accept only cash payments, which inherently means they end up serving patients who can afford to pay $100 to $250 per session.

The public or nonprofit side is typically supported by tax or philanthropic funding, and serves people with lower incomes or who aren’t covered by insurance. The government covers the biggest share of mental health care spending in the U.S. In 2019, taxpayers covered 63% of all mental health care costs — about $150 billion — including therapy and prescriptions, according to Open Minds, a health care market research firm.

When Valladares began his career 12 years ago, he wanted to treat underserved Latinx clients who had lower incomes or were immigrants, so he focused on working for nonprofit organizations. At his first job after completing a master’s degree in 2010, he earned $22 per hour or about $46,000 per year.

“I lived at home with my parents,” he said, to make it work financially.

Valladares estimates that a therapist entering a nonprofit or publicly funded agency now can expect to earn $55,000 to $70,000 per year.

“We’re losing a lot of therapists to private practice, and that’s OK,” Valladares said. “I don’t fault them. They don’t want yachts. They just want to be able to live.”

Haggling insurance companies to get paid for their services “creates a disillusionment with our mental health system,” Valladares said. “Providers like to say, ‘I don’t want to be a part of a system that just perpetuates this cycle of putting Band-Aids on much deeper issues,’ and then it pushes people into private practice. But again, if you go into private practice, who’s not getting served?”

Valladares’ focus on the Latinx community is tied to his upbringing. He recalled how some of the relatives who fled El Salvador were later hospitalized or placed on psychiatric holds because of mental health crises. One of his uncles had an alcohol addiction.

“I saw in my own family how they were impacted by immigration, trauma, the war that they had witnessed in their country and losing a piece of their identity through that,” he said.

The way he saw his relatives cope was by not talking about their issues and drinking in excess, habits he also picked up — which later led to his own alcohol addiction.

“In college, it’s normal to have a drink when you’re stressed out,” he said. “You don’t really look at it as a pattern or something you inherited from your family.”

No one questioned Valladares about his drinking until he entered a psychology master’s program at SF State when he was 23. The program encouraged students to see a therapist. When his therapist asked him why he drank frequently, he became defensive and ignored her concerns.

He went from only drinking with friends on weekends to frequently drinking at home on weeknights. Then he started canceling plans because he was too hungover. As he was nearing 30, he realized he needed to change.

“I was able to dismiss (my alcohol addiction) for years,” he said. “I started getting older and I realized that my patterns hadn’t only changed, they had gotten worse. The biggest part was meeting my wife. She was not OK with my lifestyle.”

When he decided to seek help, his insurance company denied him coverage for therapy and suggested he try a support group. He paid out of pocket for a therapist for about two years and has been in recovery for seven years.

His graduate program opened his eyes to the undiagnosed mental health conditions he had observed in his family, and how they lacked the understanding and vocabulary to talk about their issues. His mother never described herself as having anxiety, but would often say, “I just worry a lot.”

“My mom was an anxious person and I was an anxious child and we bonded over that,” he recalled. “Years later, alcohol helped me calm down.”

Eric Valladares speaks with Carolina Calderón Balladares at the Redwood City location of Family Connections. (Beth LaBerge/KQED)

His experience overcoming substance use disorder taught him that even for someone working in mental health, getting access to care is still a challenge. It also illustrated how valuable therapy can be.

“If I had not gotten into the mental health field, I would have just assumed and assimilated that that’s part of who I am,” he said. “It does make me a believer in what we do. I don’t think that there’s enough of us out there. But I do have a lot of faith that there are people out there who still want to help.”

A lack of parity

Elected officials in California also recognize that the state needs to expand its mental health workforce. One strategy is to hire more counselors and behavioral coaches — roles that require less education than psychiatrists and psychologists.

On August 18, Gov. Gavin Newsom announced a plan to add 40,000 mental health care professionals across the state. At least half of those positions will mostly be housed in schools. Newsom said the missing component to helping kids is “people willing to do this work.” Others say the system isn’t working as it should.

The federal Mental Health Parity Act, passed in 1996, ruled that insurers' dollar limits on mental health benefits couldn't be lower than their equivalents for physical health. But "that has not been in effect for most insurance companies across the country," said Naomi Allen, CEO and co-founder of Brightline, a Palo Alto-based behavioral health start-up that provides virtual therapy to kids.

She was so frustrated by the experience of trying to find therapists for her three children using commercial insurance that she co-founded Brightline in 2019.

“What we have is a situation where year over year, more and more therapists are not available through insurance. They’re going out of network. They’re in private practice,” Allen said. “And so we have this scenario that existed pre-COVID, where care was essentially unaffordable to the vast majority of families.”

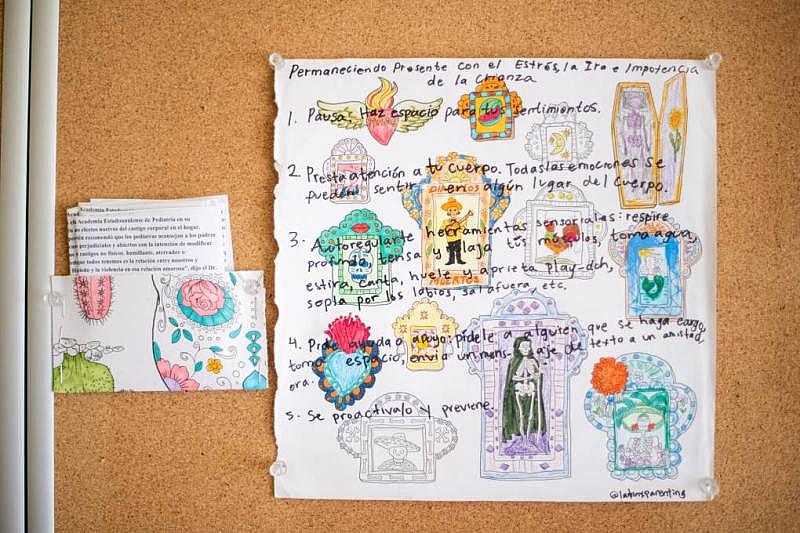

Art hangs in the therapy room at the Redwood City location of Family Connections. (Beth LaBerge/KQED)

Patricia Alvarado is one of those practitioners. She founded her online-only practice, Alvarado Therapy, about five years ago, and now employs a team of mostly bilingual therapists serving Latinx clients.

“We’re a private pay organization,” she said. “Sometimes it can be really hard to obtain payment (from insurance companies). It could take many months. There’s a lot of restrictions … like you could only work with a client for X amount of sessions and that’s it, and the client may need more.”

Some patients who have insurance end up paying out of pocket just to speed up the process of getting care.

“A lot of time passes by, and that can take away the motivation of wanting to seek services,” Alvarado said. “It shouldn't be as hard as it is. ”

Valladares provided therapy until he burned out. Then he made the switch to running programs for nonprofits like Family Connections, which works with families who don’t qualify for lower-income programs and can’t afford to pay out of pocket.

“As long as the families expressed an interest in mental health services, we’re able to provide them with those services, which has been really great,” he said.

The shift to administrative work helped Valladares stay in the field, make more money and have time to spend with his wife and two kids, ages 5 and 1.

“I still want to be in a position where I can affect change and support families in a different way,” he said. “I make it a point to go out there and make a connection with the people my organization is serving and definitely not lose sight of why I do what I do.”