COVID forced Bay Area families to make agonizing elder-care decisions. Is there a fix?

Emily DeRuy reported this story while participating in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2021 California Fellowship.

Other work by her includes:

Getting older doesn’t have to be scary. Things to consider as you age

Christie Bilikam, right, poses with her husband, Ed, left, and his twin brother, Bob, who both suffer from dementia.

As the deadly winter surge in coronavirus cases began last November, Fred Mekata was doing something that had become unthinkable to millions of Americans: moving into an assisted-living facility.

The love of his life, Ruth, had been diagnosed with dementia a couple of years earlier. Gone was the independent, sharp woman he’d shared his life with for more than 56 years. Over were the spontaneous weekend trips to Spain, a perk of her years with American Airlines. Instead, the pair were puttering around their 3,000-square-foot home in Danville, Fred trying to take charge of daily tasks like cooking that had always been Ruth’s domain and struggling to come to terms with the changes in their lives.

So he packed up their belongings. Sold the house. Moved into a second-floor unit at The Watermark at San Ramon. Hunkered down for a quarantine. All as the pandemic raged on.

Fred Mekata helps his wife, Ruth, at her bedtime in their unit at The Watermark in July 2021. (Dai Sugano/Bay Area News Group)

Months earlier on the other side of the San Francisco Bay, Lucinda Tinsman was making a very different calculation, but one also motivated by survival. Her frail mother, Marilyn, had spent years at Silver Oaks in Menlo Park. But when the memory care facility shuttered its doors to visitors and COVID crept in anyway, Tinsman pulled her mom out. She brought the woman with whom she hadn’t shared a roof since her teenage years to her house, setting up a hospital bed in the dining room and upending the life she shared with her partner and young sons.

“I really made a fortress out of our house,” Tinsman recalled.

Across the Bay Area and beyond, COVID-19 changed how families approach the emotionally wrenching task of caring for elderly relatives. They’re increasingly considering home care, having second thoughts about nursing homes and assisted-living facilities, and demanding reassurances: What would happen if the facility locked down? And where is the best place to keep my loved one safe during the next outbreak?

The pandemic laid bare the pitfalls of a patchwork care system, prompting conversations at kitchen tables and doctor’s offices and the halls of Sacramento about not only the future of caregiving, but the peril of aging in America.

The question now on so many minds, said Mike Dark, who until recently worked as a staff attorney with the organization California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform: “Is it time to do something different?”

Darkest images of the pandemic

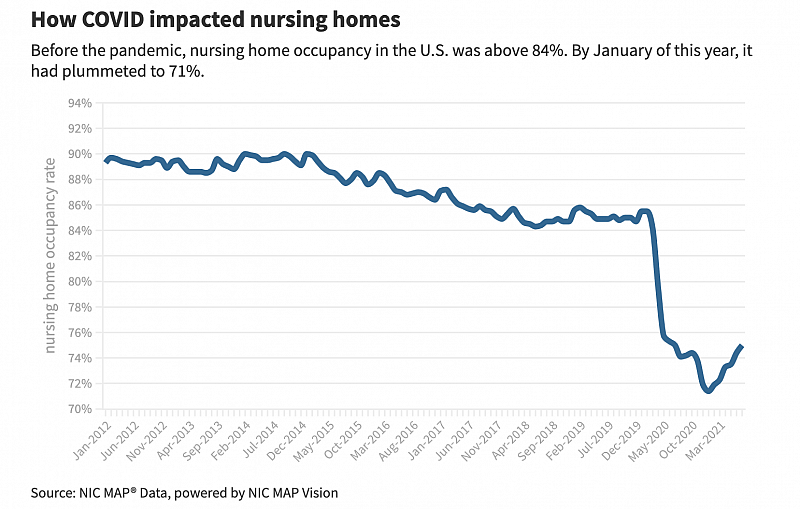

There is no question that the pandemic took an exorbitant toll on America’s elder-care homes. In California, less than 2% of seniors live in nursing homes, yet those facilities have accounted for roughly 13% of the state’s COVID deaths, according to state data. And the exodus from nursing homes was just as telling: Before COVID, nursing home occupancy in the U.S. was above 84%, according to the National Investment Center, which tracks occupancy. By January of this year, it had plummeted to 71%, and is nowhere close to fully rebounding.

Some of America’s darkest images from the pandemic are of elder-care facilities, grossly under-staffed, lacking in PPE, and filled with confused residents locked down and cut off from loved ones.

“Families had to crawl through bushes just to be at the windows to see people,” said Celia Maurice, a Peninsula woman who is caring for her 93-year-old mother at home. “It’s insane how that had to work.”

Many facilities struggled to manage basic infection control, said UCSF geriatrician Louise Aronson, who visited a number of elder-care homes during the pandemic.

And many of the problems that the pandemic exposed are systemic. Low-wage workers who were scraping together a living with jobs at multiple facilities unwittingly carried the virus from place to place. Residents suffered from the physical and mental toll of social isolation. Families were left grasping for answers about how nursing homes were spending money intended for care.

Overall, COVID has claimed the lives of more than 13,000 people at nursing homes and assisted living facilities across the Golden State.

In the wake of the pandemic, lawmakers in Sacramento introduced a package of bills known as the PROTECT Plan, and Gov. Gavin Newsom signed legislation this month that will require facilities to submit financial reports and boost citations for bad actors. But a proposal to strengthen the standards around who can run a nursing home stalled and calls for higher staffing levels have been ignored.

Chuck Cole, chief operating officer at the Chaparral House in Berkeley, says nonprofit nursing homes like his are trying to break the mold. He receives questions about COVID deaths and vaccination rates from worried family members and prospective residents, and is proud to note that the home had no deaths from the virus.

Chaparral House has mostly private rooms which makes quarantining people easier, he said. Unlike other facilities with high staff turnover, a third of Chaparral House staff have been with the organization for more than a decade, enjoying decent wages and good benefits, which made working as a team amid the pandemic easier, he said.

Still, breaking the mold doesn’t come cheap. A private room without insurance costs $14,400 a month.

Cruel reality of home care

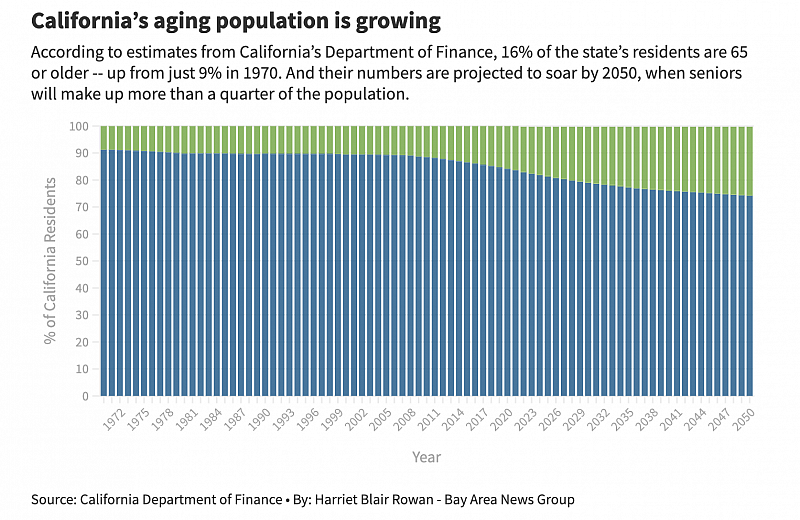

California is home to more than 7 million seniors. That number alone would rank as the 15th most populous state in the U.S. But less than 10% live in nursing homes or assisted living facilities. And now even more people are opting for something different.

Those are people like Christie Bilikam, a Palo Alto woman who shares a home with her husband, Ed, and Bob, his twin. The brothers turn 85 in late October — and both suffer from dementia. She used to think Bob might be safer in a facility, but the vulnerability and isolation she saw during the pandemic changed her mind. It “was just catastrophically inhumane and damaging in ways that we’ll never recover from,” she said.

A November 2020 AARP survey found that 8 out of 10 adults 40 and older now prefer in-home care for themselves or an elder loved one. But here’s a problem: Nearly half of those surveyed incorrectly believe Medicare will help pay for it.

Bilikam knows the cruel reality. Round-the-clock caregivers help the brothers with everything from bathing to dressing to feeding. At $30 an hour, though, the tab is more than $20,000 a month — a fact that brings heart-pounding fear every Friday evening when Bilikam does the payroll.

Christie Bilikam works on the daily medicine list for her husband, Ed, and his twin brother, Bob, in July 2021. (Dai Sugano/Bay Area News Group)

At 74, she imagined life would be different. “I thought I would be on cruises,” she quipped with a sharp laugh, as she sat surrounded by sewing projects and Ed’s book collection — and, now that Bob has moved in, his model battleships, paintings and a prized ‘68 Mustang that has sat parked in the driveway since it was shipped in February last year from his former home in Ohio.

In many ways, she is lucky. She’s a homeowner. There are, for now, funds to draw on, though the savings from Ed’s engineering career and Bob’s government pension are diminishing quickly. But for families without significant savings, there are few options, leaving many to provide care on their own.

Bilikam got a taste of that when the pandemic first hit and she made the agonizing decision to let the paid caregivers go, cooking up to nine meals a day and trying to maneuver two much-larger, sometimes-stubborn men from place to place.

“It was emotionally horrifying, it was physically horrifying and it was very traumatic,” Bilikam recalled of the six months without caregivers before everyone was vaccinated. “But I remind myself that I’ve never lived in a country where I have to gather my important belongings, throw them in a pillowcase and run for my life because my village is being bombed.”

COVID exacerbates burden on caregivers

When COVID arrived, experts say, the pandemic revealed just how fragile the home care system is, and how much it relies not only on the unpaid labor of loved ones but especially on women of color who toil away as home caregivers at low wages with little recognition.

Ana Nicho Luu is a paid caregiver herself, but she had to scale back her work during the pandemic to tend around the clock to her 90-year-old mother, Maura Nicho.

Ana Nicho Luu helps her mother, Maura, settle in her bed at night in their Santa Clara home in August 2021. (Dai Sugano/Bay Area News Group)

Before the pandemic, Luu’s mother happily rode off to “school” — her term for the adult day care site in Mountain View run by the nonprofit Avenidas — five days a week. Because Nicho is low-income, the service is covered by Medi-Cal and her time there gave Luu a chance to work or run errands.

But when the virus arrived and the center shuttered its doors, Nicho’s routine ground to a halt and the typically sweet Peruvian immigrant, who has Alzheimer’s, became more confused and aggressive. She wandered into the neighborhood, took a fall and fractured her knee.

The break marked a turning point. A half-completed puzzle the pair had been working on sat for months on the coffee table in the family’s rented duplex, abandoned as Luu turned her attention to nursing Nicho back to health. But the idea of placing her mother, the woman who had raised her and now depended on her, in an assisted-living home filled Luu with dread.

Nothing about it is easy. Nicho developed a habit of picking things up and discarding them, including Luu’s wedding ring. Luu’s husband said at one point that he felt like he lived in a home for the elderly. And while Nicho has returned to the daycare center a few days a week, any respite for Luu is brief. Still, she has no regrets.

“Nobody can care deeply like the family,” she said.

Can we fix a disjointed system?

Even before the pandemic, experts in elder care say, the process of finding long-term care was disjointed and confusing — and downright inhospitable to people without significant resources. Different types of facilities have different rules, are overseen by different agencies, and require different types of insurance.

“The pandemic has shown the cracks and problems in our system,” said Paula Wolfson, a social worker with Avenidas who helps families navigate the process of providing or finding care for aging relatives.

In the last year and a half, Wolfson has fielded hundreds of calls from people worried about everything from care options to wills. The calls often come from spouses and partners concerned not so much about the family members they care for getting COVID, but about what would happen to their loved ones if they themselves got sick or worse.

The answer largely depends on a person’s resources, network, and ability to negotiate endless bureaucracy. Those who are lucky find or stumble upon people like Wolfson. She knows the elder care landscape inside and out after decades immersed in it and acts as a choreographer, helping people make the best decisions given their circumstances. But there is no central hub, no clear signposts for what to do or where to go when someone you love needs help.

At the federal level, President Joe Biden proposed spending $400 billion on improving care, in part by expanding access to long-term home care for people who qualify for Medicaid. California pays for some home care for low-income residents through the In-Home Supportive Services Program, but it doesn’t cover 24-hour care.

And the U.S. remains an outlier among other industrialized countries in that it does not provide long-term care as a benefit for all seniors.

California expanded Medi-Cal to undocumented people, giving thousands of low-income elderly residents access to some care. But Newsom vetoed a bill advocates said would have expanded a program that helps people who qualify for skilled-nursing care remain in their community. In other places, like the Scandinavian countries, care in facilities and at home is highly subsidized.

“It’s certainly personal to me,” said Assemblymember Ash Kalra, a San Jose Democrat who, in addition to his work in the legislature, cares for his aging father. “We don’t do enough and it’s a shame.”

Navigating for deeply personal solutions

Fred Mekata, 84, who served his country in the U.S. military even after being forced to spend part of his childhood in internment camps during World War II, didn’t think twice about what was best for his family.

He had visited many assisted-living facilities before the pandemic and would have moved with Ruth into The Watermark sooner if COVID hadn’t delayed its opening.

Framed pictures of the Mekatas, taken years before Ruth was diagnosed with dementia, sit in their bedroom in July 2021. (Dai Sugano/Bay Area News Group)

Between savings earned over years as a self-proclaimed “techie” and the windfall from the sale of his Danville home, he and Ruth, 82, are able to pay roughly $8,000 a month out of pocket for their new living arrangements.

“It’s been a godsend,” he said, sitting next to Ruth in their cozy apartment, drawings from the grandkids taped to the kitchen cabinets. Now that residents have been vaccinated, there are activities and exercise classes, a dining hall and relaxing common areas that evoke a high-end ski lodge. Someone else handles the cooking, the cleaning and the maintenance, freeing him up for the most important thing: caring for Ruth. “If we were still living at home, I don’t think that we would have survived.”

Many families — both with means and without — lean on children and grandchildren for help. The Mekatas visit their daughter for home-cooked meals each week and Ruth stays at her house for a few hours some days so Fred can golf with friends. But Fred was adamant that would be it. “I didn’t want her to sacrifice her family for us,” he said.

For now, the pandemic hasn’t changed a fact that Mekata, Bilikam, Luu, Tinsman and countless others face on a daily basis: Sooner or later, every one of us will be left to navigate an unforgiving system for a deeply personal solution about the ones we love.

For Tinsman, taking her mother out of the Menlo Park facility where she had lived until the pandemic was a significant burden. She already had two young boys at home and her own health struggles. And the facility Marilyn was in was actually “lovely,” Tinsman said.

But “I don’t think she would have lasted very long,” she said, especially once the virus crept in.

Lucinda Tinsman quarantines her mother at her home in Menlo Park last March 2020. (Karl Mondon/Bay Area News Group)

Tinsman was able to coax her to eat and drink, and even if her mother couldn’t say so, Tinsman thought her body language indicated she was more comfortable being with familiar faces.

Marilyn ended up in the hospital a couple of times. At one point, a reverend administered last rites. But once she was home, she’d perk up again.

“I think she really liked being here,” Tinsman said.

A little more than a year into their pandemic life together, Tinsman woke up one Sunday in late May and discovered her mom had passed away. The loss brought both grief and peace, in a time of crisis that so desperately calls for change.

“It was hard but it was really nice she was here and I knew I did the best I could,” Tinsman said. “It just felt like it was this very long circle, like coming home.”

Staff Writer Harriet Blair Rowan contributed reporting.

Emily DeRuy reported this story while participating in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2021 California Fellowship.

[This article was originally published by The Mercury News.]