Is the crackdown on opioids failing patients?

This story was produced as a project for USC Annenberg's Center for Health Journalism California Fellowship.

Other stories in the series include:

How ER docs could play a key role in fighting the opioid epidemic

Is pot the answer to keeping seniors in pain off opioids and other prescription drugs?

Jan Curtis and her dog, Belle, at a park near her Huntington Beach home on April 27, 2018. Curtis hopes she's nearing the end of a decades-long struggle with chronic pain and the opioid dependence that came with it. Jill Replogle

Jan Curtis was only in her mid-30s when her lower back started hurting.

Curtis, a hospital nurse, lifted patients onto stretchers. She helped them in and out of beds and wheelchairs and moved around heavy medical equipment. The work took a toll.

So she switched to a desk job, hoping to put less stress on her body. It was the early 1990s, and she didn’t want to take medication for her pain. These were pre-opioid pain treatment days.

"I think I bought myself some time, a good 10 years," says Curtis. "But by the time I was in my 40s, I was really in excruciating pain."

By her mid-50s, she had two back surgeries and both her hips replaced.

And now opioids were common. She was introduced to a full range of powerful — and powerfully addictive — pain relievers, including Percocet, OxyContin and fentanyl.

Then, as a deadly opioid epidemic in America made clear the perils of those drugs, Curtis had trouble getting the painkillers she’d come to count on.

"The pendulum was swinging toward, 'We're taking you away from your narcotics,' which really scared me," she says, "because if I didn't have the narcotics I would be in such unbearable pain and bedridden."

FEWER PRESCRIPTIONS BUT MORE DEATHS

Jill Replogle

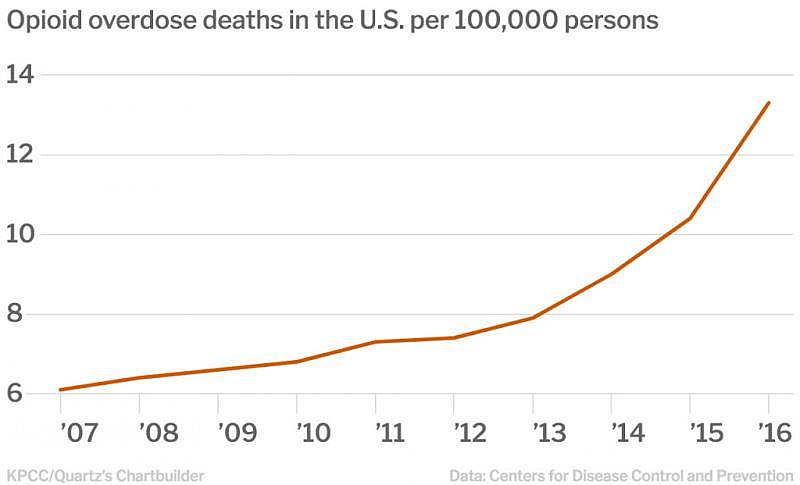

In 2016, more than 42,000 people in the U.S. died of opioid-related overdoses, including at least 2,000 in California, according to the most recent data available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the California Department of Public Health.

The national opioid epidemic has evolved rapidly in recent years, from prescription pill abuse to heroin and now fentanyl and other, increasingly powerful synthetic opioids. The dizzying pace has left those trying to stem the rising death rate struggling to keep up.

Many chronic pain patients are middle-aged and older adults, who are among the highest users of prescription opioids. There’s not much evidence to suggest opioids are an effective treatment for chronic pain. Still, policies designed to curb abuse have left some feeling stranded.

Curtis, now 63, says doctors would refuse to accept her as a patient because of the high doses of narcotics her body had become dependent on. At one point, her main pharmacy refused to keep filling her prescriptions.

Jill Replogle

"We are overreacting to the need to lower opioid prescribing by punishing patients," says Dr. Kelly Pfeifer, who leads the California Health Care Foundation’s efforts to address the opioid epidemic.

As opioid overdose deaths skyrocketed, regulators cracked down on so-called "pill mills," medical practices that handed out large quantities of prescription opioids. At the same time, professional organizations, insurance providers and state and federal agencies issued a series of rules and recommendations that pushed doctors to strictly limit opioid prescriptions and to be on the lookout for patients suspected of abusing prescription drugs.

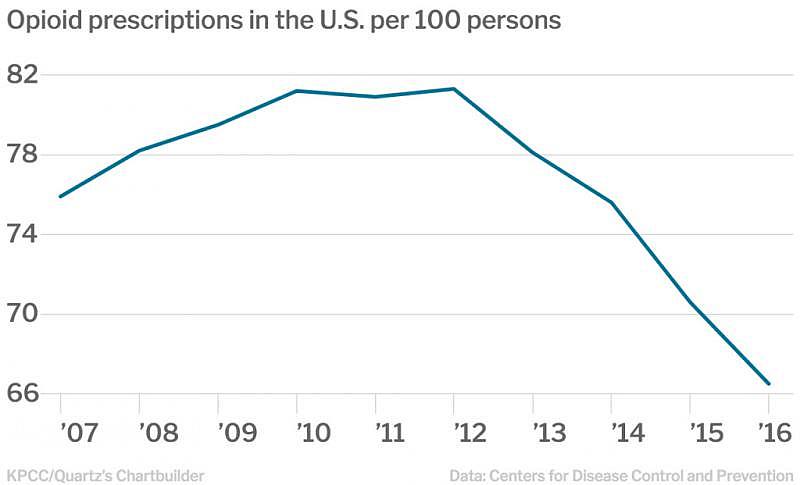

It worked: Prescriptions for high-dosage opioids dropped nearly 50 percent between 2008 and 2016, according to the CDC. Prescriptions for all opioids dropped 18 percent from the high point in 2012. That year there were more than 255 million opioid prescriptions, the equivalent of 81 per every 100 persons.

But even as prescriptions drop, overdose deaths continue to rise. And some patients are seeking out heroin or other illicit drugs as a substitute. There also are some reports that suggest patients have committed suicide after being cut off from opioids.

Guidelines from the CDC and the California Department of Public Health urge doctors to work with long-term opioid users to safely decrease their dosage and to help get patients who have become addicted into treatment.

But many doctors are choosing to extract themselves from the problem by renouncing opioids completely, says Pfeifer.

"We're seeing doctors say, 'I don't use opioids for chronic pain. Good luck,’" she says.

The medical community needs to own up to its role in fueling the epidemic and work harder to repair the damage, Pfeifer says.

"We ... have harmed people by putting them on high-dose opioids and it's our responsibility to work with every individual one of them to get them down to safer, lower doses to make sure they stay safe," she says. "And that's not happening."

We're also failing to treat patients who become addicted to opioids, says Pfeifer.

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, 8 to 12 percent of long-term opioid users develop an addiction, and some studies suggest that number is much higher. And yet not enough doctors are stepping up to provide treatment, Pfeifer says.

The Urban Institute estimates that between 166,000 and 245,000 Californians with opioid use disorders don't have access to medication-assisted treatment.

TOO CLOSE TO A STATISTIC

Oxycodone pain pills. JOHN MOORE/GETTY IMAGES

One day in 2014, she was alone in her Huntington Beach home when she began to feel lightheaded. She had been taking high doses of oxycodone and wearing a fentanyl patch to ease the pain that persisted despite her multiple surgeries.

"I just felt like my blood pressure was dropping," she says. "And I was getting tingling, like you're going to pass out."

She called 911, and when paramedics arrived, they found that her blood pressure was dangerously low. She told them she suspected it might be because of the fentanyl patch.

"As soon as they took it off, I started to come around," Curtis says. "But that was a turning point for me."

She decided to find a doctor who could help her get off opioids. She turned to Dr. Andrew Germanovich.

WHAT MAKES OPIOIDS SO DEADLY

Dr. Andrew Germanovich's drawing depicts how opioids interact with the brain function. He draws it for all new patients. Jill Replogle

From behind his desk in a sleek medical building next to St. Joseph Hospital in Orange, Dr. Germanovich grabs a piece of scratch paper and draws what looks like a boxing glove in the left-hand corner.

"This is a picture of the brain," says the 38-year-old anesthesiologist and pain specialist. "And this is a spinal cord," he says, drawing lines across the page out from the area of the glove's wrist.

Germanovich draws the abstract illustration for all of his patients, including Curtis. He uses it to explain how the body tells the brain that it’s in pain, and how opioid painkillers work to block that information. And the drawing also helps him to educate his patients about why it's so easy to get addicted to opioids, and just how deadly they can be.

Opioids, he explains, bind to receptors in the spinal cord to help shut down pain signals transmitted from other parts of the body. The danger, he says, is that opioids also shut down the signals that tell your brain to breathe.

"The opioid doesn’t discriminate which electrical signal it turns off," says Germanovich. "It turns off almost all of them."

The drive to breathe is further dampened by alcohol and benzodiazepines, a class of drug commonly used to treat anxiety — and often a factor in opioid drug overdoses. Finally, a weakened kidney or liver can fail to properly metabolize opioids in the body, leading to a buildup of toxins.

THE BODY’S DOWNWARD SLIDE

Germanovich says he sees lots of patients like Curtis, middle-aged men and women whose bodies are naturally deteriorating. He says it’s no wonder that middle-aged people are dying of opioid overdoses at the highest rates in California. They’re the ones most in need of pain relief.

"Degenerative neck and back disease typically starts to come right after the age of 45," he says, "and doesn't manifest itself in big ways until someone is almost 50."

In 2016, 55- to 59-year-olds topped all age groups for the highest rate of opioid-related overdose deaths in California, followed by 60- to 64-year-olds, according to the most recently available data from the state public health department.

More than 80 percent of those deaths were attributed to prescription opioids.

To treat pain, Germanovich uses a combination of strategies, including physical therapy, injections, non-narcotic pain relievers and, when needed, opioids. But he is frank with patients about the risks, and about their responsibilities if prescribed opioids.

Germanovich makes patients sign a contract before treatment in which they agree to random drug screenings and, if addiction sets in, to work with him to address the problem. He educates patients about the withdrawal they may experience when tapering off opioids and benzodiazepines. Germanovich also prescribes medication to manage withdrawal symptoms.

HOPE FOR AN OPIOID-FREE FUTURE

Last year, Curtis had yet another surgery, this time for degenerative disc disease. It has given her some relief. Since that surgery, Germanovich has been helping her taper off opioid pain relievers.

"He's been my cheerleader," Curtis says.

She’s now down to 10 milligrams of methadone a day and is hoping to be off of opioids completely by summer.

On recent dog walk with Belle, her Coton de Tulear, Curtis says she’s feeling great.

"I have more enthusiasm, I'm engaged in life, not so depressed like I was," she says. "Those medicines can make you feel really depressed."

Curtis and her husband are planning to visit their grandchildren in Philadelphia later this month. It’ll be her first time traveling, hopefully pain-free, in a decade.

[This story was originally published by KPCC.]