The Hidden Toll of Caregiving in the Vietnamese American Community

The story was co-published with Nguoi Viet Daily News as part of the 2025 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.

Thuy Vu helps her mom monitor the blood pressure. (Photo: Courtesy of Thuy Vu)

Thanh Nguyen, a Garden Grove resident, has cared for her bedridden mother for nearly 30 years.

Thanh, her mother, and grandmother joined Thanh's father in the US in 1986. Then, in 1994, when Thanh was 19, her mother, who had been healthy, suddenly began to have difficulty walking. "After many tests, we found out she had MS," Thanh recalled.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a disease that damages the protective covering of nerves, leading to numbness, muscle weakness, difficulty walking, vision changes, and many other symptoms.

"I had to juggle studying, taking care of my mother, my brother, and my aging grandmother. It was overwhelming. I was constantly stressed, overloaded, and exhausted," she said.

In California's Vietnamese American community, caregivers like Thanh Nguyen silently endure their own health crisis while tending to disabled or elderly family members, trapped between cultural expectations of filial duty and the crushing reality of round-the-clock care.

Though data from the 2020 California Health Interview Survey (CHIS) conducted by UCLA reveals caregivers across the state struggle with financial instability and deteriorating physical and mental health, experts say the situation is particularly acute in Vietnamese households where cultural norms discourage seeking help or admitting exhaustion, creating an invisible epidemic of caregiver suffering that receives virtually no institutional support.

When it comes to health care, the Vietnamese community often thinks of patients, the elderly, or people with disabilities who need support. Yet few people recognize that caregivers themselves—those who silently shoulder the responsibility of tending to the needs of their loved ones—also endure profound physical and emotional wounds.

Numerous studies have shown that caregivers are at greater risk of negative outcomes, such as reduced use of preventive health services, increased physical and mental health deterioration, and the loss of time needed to nurture other relationships and responsibilities within their families and workplaces.

The study of CHIS on “Self-Reported Health Status of Vietnamese and Non-Hispanic White Older Adults in California” showed that Vietnamese participants were more likely than their white counterparts to express a need for mental health support, yet were less likely to have had medical providers address these concerns with them.

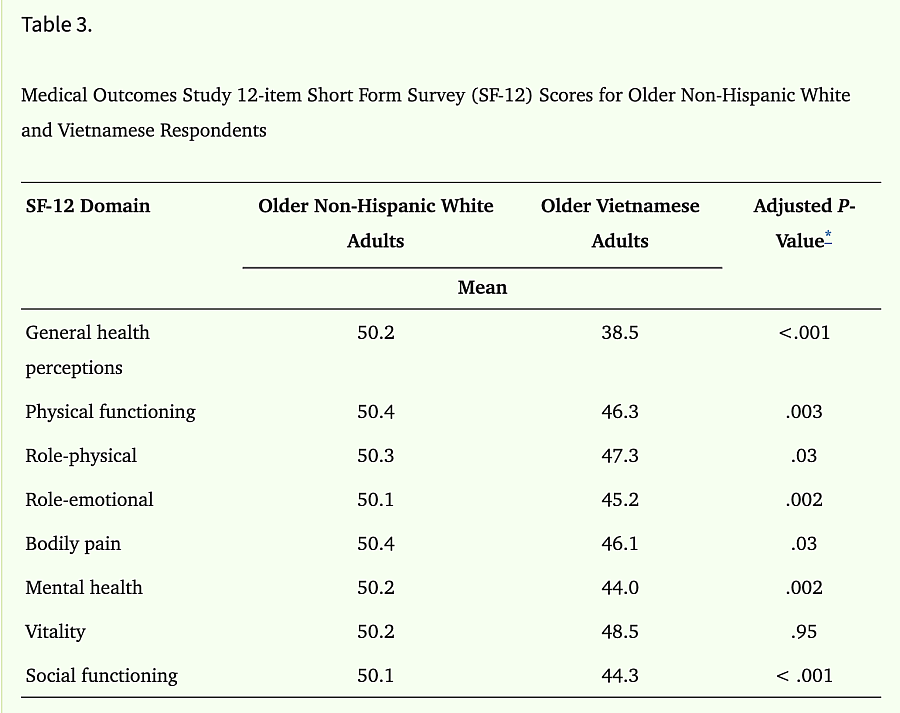

Furthermore, the study reported significantly poorer health outcomes in five out of eight categories surveyed (physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health problems, pain, general health perceptions, energy and fatigue, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, and psychological distress and well-being).

Medical Outcomes Study 12-item Short Form Survey (SF-12) Scores for Older Non-Hispanic White and Vietnamese Respondents.

Note: Scores range between 0 (lowest) and 100 (highest), with higher scores representing better health. Means transformed using standard T-score metric relative to the U.S. general population.

The sample size was larger for general health perceptions (N = 25,517; Non-Hispanic white, n = 25,158; Vietnamese, n = 359) because this survey item was include in both the California Health Interview Survey (CHIS) 2001 and 2003, but the remaining survey items were included only in the CHIS 2003 (N = 13,919).

*

Regression analyses were adjusted for age, sex, and education.

Published in final edited form as: J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008 Jul 15;56(8):1543–1548. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01805.x

These findings suggest that clinicians working with older Vietnamese patients should recognize the elevated mental health risks in this community and take the initiative to engage in conversations about mental well-being.

"I once didn't want to live anymore"

Thanh’s family had dreamed that she would become a doctor, but after having to inject steroids into her mother daily to relieve her MS flares, Thanh developed signs of trauma and gave up her dream of becoming a doctor.

"My younger brother was only 7 at the time, and my grandmother also helped care for my mother because I was attending university and could only care for my mother on weekends," she said.

Pausing for a moment, she added, "My mother had a miscarriage with my youngest sister ... I don't remember exactly when, but not long after that, my parents divorced, and my father gradually faded from my memory."

Thanh recounted that while pursuing her master's degree in public health at UCLA, she spent a lot of time each day caring for her mother.

"I once didn't want to live anymore," Thanh recalled.

She said she had researched various suicide methods.

"I don't know why ... but suddenly, I had an awakening. If I died, what would happen to my family? I stopped crying and chose to become stronger," she said.

"I wanted to 'end' everything"

Thuy Vu, a former English teacher at a high school in the Huntington Beach Unified School District, has been struggling to balance work and taking care of her mother for the past 11 years.

In 2014, during Lunar New Year, Thuy’s mother was hospitalized after suffering a stroke, upending their family life.

"This wasn't the first time my mother had a stroke. Later, after learning more, I found out she had suffered several minor strokes before without our knowledge," said Thuy, a 31-year-old Santa Ana resident. She confided that her father left the family in 2018, and she has not spoken to him since.

Although Thuy’s brother initially helped with caregiving, when he moved out, Thuy became the primary caregiver.

"Right after my mother’s stroke, I had to juggle college, a part-time job, and spend most of my time preparing meals for her because she had several diet restrictions and couldn’t cook for herself," she said.

Meals had to meet her mother's nutritional needs—providing protein, fiber, and vitamins—and the food had to be soft because her mother had trouble chewing and swallowing due to the aftereffects of the strokes.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Thuy feared the risk of infection and requested to teach from home. Inside their home, all family members wore masks to protect her mother.

Even after the pandemic officially ended, they continued to wear masks at home, worried that her mother’s weak immune system couldn't withstand any infection.

"I was overloaded and exhausted, but I kept pushing myself to fulfill my caregiver responsibilities. I didn't share it with anyone. I thought I had to handle it alone because I didn't want to bother others," Thuy added.

She silently endured day by day, until one day she hit a wall.

"That day, the emotions inside me were overwhelming. I wanted to end everything!"

While she’d had suicidal thoughts as a young girl, this was worse. "In 2022, at age 27, was when I thought about ending my life the most," she said.

Caregiver support services are needed

According to CHIS’s data, in 2020, nearly 14% of caregivers reported suffering physical or mental health issues due to caregiving in the past 12 months.

"Nearly half of caregivers (44.4%) reported experiencing some degree of financial stress due to caregiving, with about 1 in 5 (20.5%) saying caregiving was 'somewhat' to 'extremely' financially stressful."

Pauline Le, a social worker and family consultant at Caregiver Resource Center OC (CRC), a nonprofit in Orange County established in 1988, provides support services for caregivers of aging or ill family members.

Pauline Le (far left) and the staff of Caregiver Resource Center OC at the workshop to assist caregivers with senior law and end-of-life planning. (Photo: Nhien Tra Nguyen)

Vietnamese caregivers attending Caregiver Resource Center OC workshop. (Photo: Nhien Tra Nguyen)

Looking back on more than 25 years of counseling and caregiver support experience, Pauline said that the center’s clients often "experience stress, both physical and mental health problems after prolonged caregiving."

She says that financial stress is a major contributor to caregivers’ mental health struggles, especially among families who don't qualify for Medi-Cal, California’s version of the low-income federal-state health insurance program

Before providing services, CRC conducts an in-depth screening and assessment process.

"Asian caregivers, in this case, Vietnamese caregivers, often respond differently during assessments due to stigma and a tendency to downplay their depression burden" Pauline explained.

"Some seniors, who are the main caregivers for their family members, have serious health conditions themselves but delay treatment out of fear that no one will care for their loved ones during their hospitalization," she added.

Currently, CRC serves about 140 Vietnamese families, offering services such as counseling, support groups, workshops on caregiving, and information on county resources, including financial assistance for caregivers.

Workshops also cover legal topics, such as power of attorney and end-of-life planning.

Pauline noted a promising sign that Vietnamese people are becoming more open to receiving mental health support.

"In the past, most support group participants were women, but recently, half are men, indicating that stigma within the community is decreasing," she said.

CRC's support group coordinators are mostly master's-level social workers fluent in Vietnamese. Additionally, CRC collaborates with other community organizations like Orange County Asian Pacific Islander Community Alliance (OCAPICA), and the Vietnamese American Cancer Foundation (VACF).

Despite its efforts, CRC struggles with limited budget and staffing, relying mostly on word-of-mouth referrals.

Opening up is the key

Many Asians, especially Vietnamese, often struggle silently due to stigma and fear of burdening others. Over time, they forget the importance of opening up.

Thanh Nguyen noted that everyone has their own ways of coping. For her, finding comfort in short gatherings with friends or brief trips to other states helped her rejuvenate before resuming her caregiving duties.

"I hope people can open up more and accept outside support, such as joining support groups and caregiving workshops. It's important to seek help from siblings or relatives to lighten the load and avoid burnout like I experienced," she advised.

In addition to opening up about their struggles, many Vietnamese Americans turn to religion as a culturally meaningful coping strategy.

A helpful resource on this topic is a course handout by Dr. VJ Periyakoil, Stanford geriatrics professor, who serves as Course Director and Editor-in-Chief. The handout, focused on Vietnamese American Older Adults, includes a case study of a 78-year-old husband caring for his 66-year-old wife. His reliance on Buddhism and folk beliefs provided him with emotional strength and helped him manage the challenges of caregiving.

Thanh’s husband now takes turns caring for her mother so she can have time for herself and focus on her work managing a nonprofit specializing in health care and community services.

It also helps that because her mother qualified for Medi-Cal, her family is able to cover her medical expenses, she said.

Thuy Vu and her family also benefit from coverage purchased on the Affordable Care Act, helping them manage the high costs of medical care.

"My family had just gotten insurance at the beginning of 2014. A month later, my mother had her stroke. Without the coverage, we might have had to sell our home to cover her hospital bills," Thuy said.

As Congress explores ways to reduce the federal deficit, Medicaid funding is under threat, especially following the GOP-led House's approval of a budget framework that excludes Democratic support. Some House Republicans are pushing for Medicaid cuts, which could severely impact family caregivers and individuals needing long-term care.

Medicaid is a joint federal-state program that provides health insurance for low-income individuals. It is the largest funder of long-term care for elderly and disabled people, covering over 50% of the $415 billion spent annually on such services.

Medicaid pays for 60% of extended nursing-home stays, supporting nearly 1 million people—mostly those with limited income and assets.

Any reduction in Medicaid funding could leave vulnerable populations—particularly the elderly and disabled—without essential long-term care support.

Thuy has her own therapist to help her cope during crises. She finally sought help after a prolonged period of enduring.

She also advised caregivers to speak up and seek help from mental health professionals or relatives, saying that asking for help is the key to unlocking emotional knots.

"Not only caregivers but also patients should open up more. My mother used to avoid gatherings out of shame over her illness and changes in her physical appearance, but ever since she started participating in social activities, her mental health has improved," Thuy said.

This project was supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, and is part of “Healing California”, a yearlong reporting Ethnic Media Collaborative venture with print, online, podcast and broadcast outlets across California.