Current and former Rankin residents remember the past, envision the future

This story was produced as part of a larger project led by Rich Lord, a participant in the USC Center for Health Journalism's 2018 Data Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

Charges lodged in North Braddock arrest

Growing up through the cracks: The children at the center of North Braddock's storm

Growing up through the cracks: Policing change brings cops up close with kids in poverty

Rankin, Pennsylvania: Fighting 'the depressed mindset'

Pittsburgh's neighborhood boosters face changing landscape

Where fighting poverty is a priority

Growing Up Through the Cracks: Mapping Inequality in Allegheny County

A mother moves from McKeesport to Glassport to try to better her family’s chances

Growing up through the cracks: North Braddock: Treasures Amid Ruins

(Photo Credit: Michael M. Santiago/Post-Gazette)

Ralph Johnson, 64, grew up in Rankin’s Hawkins Village, the biggest low-income housing complex in one of the region’s poorest boroughs. He made a career in information technology, and now lives in Miami, though he comes home often to visit his mother.

He is evidence that success can sprout from even the least-advantaged places.

“I tell all my friends that my experience in Hawkins Village/Rankin prepared me for life anywhere in the country,” Mr. Johnson wrote this week, in an email response to the first part of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette’s series Growing up through the Cracks, which featured the borough of some 2,200 people, where roughly half of the children are living in poverty.

His advice to the teens featured in the stories: “Follow your dreams like I have.”

But he acknowledged that there are barriers: crime, drugs and a hard-to-ignore sense of isolation and marginalization. This week politicians responded to the data and stories in the series by calling for consideration of municipal disincorporation, revenue sharing and other measures to level the playing field between the region’s haves and have-nots.

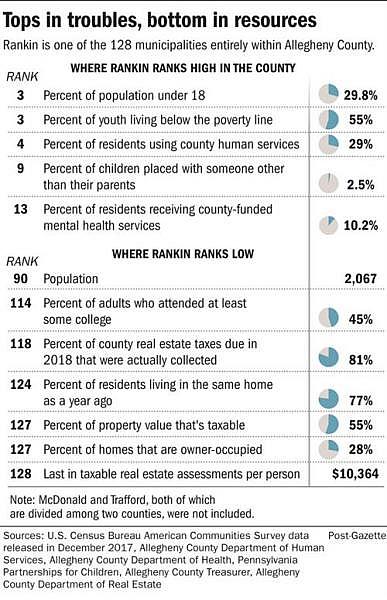

Rankin has the third-highest concentration of youth in the county, but also the fourth-highest rate of residents using Allegheny County human services. It has the lowest or second-lowest rate of home ownership, percentage of property that is taxable, and taxable property value per capita, among municipalities that are entirely within the county.

"Everyone is trying, and struggling to do better and move up,” said Brittney L. Pepper, who spent half of her childhood in Rankin, and is now an e-discovery attorney at Reed Smith and president of the board of the Rankin Christian Center. "These are all people pushing us down and keeping us down, and you can't get ahead."

That creates a mentality in which some people claw at others, rather than collaborating, she said. “Everyone just knocking each other down, like crabs in a barrel.”

But does it have “the depressed mindset,” as James Weems, a well-traveled entrepreneur and Rankin resident, described it in the series?

“The depressed mindset -- I don't think that's most of the population here,” said Joan Neal-King, 84, a longtime resident of Rankin. However, she acknowledged that many of the activities that existed for young people in decades past have fallen away.

“There is no Little League baseball. There is no real viable program for the youth here,” she said, noting one exception -- activities at the Rankin Christian Center.

She held out little hope for a governmental solution. “It's up to us to do something, and it's not [the responsibility of the borough] council,” she said. But whereas in the past, people organized around churches, she noted that these days attendance is modest at houses of worship in the borough.

So where would the grass roots take root? There’s little left in terms of natural, informal gathering places, other than the nationally known Emil’s Lounge. The only shopping options are a convenience store and tiny Carl’s Cafe. The last bar, Deb’s Place, closed shortly after Mr. Weems bought it, when he found himself unable to secure the liquor license.

The Rankin Christian Center, a private nonprofit with a food bank, counseling and children's activities including a summer day camp, is one neighborhood rallying point, noted Gary White, one of its board members.

He shared the story of a first-grader with “an electric personality” who was having trouble in school. “We discovered that he did not know the alphabet, not at all,” Mr. White wrote, in an email response to the series. The center “called in a teacher volunteer and in two weeks, the boy knew 22 out of 26 letters.”

The center also has programs that help teens to prepare for post-high school life.

“It gives [young people] a place of refuge. They don't have to go out in the street,” said Ms. Pepper, who now lives in Wilkins.

In its industrial heyday in the 1950s, Rankin had lots of spots to rub elbows, wrote Rita Lebovitz Kohn, who grew up in Squirrel Hill, but spent many days at Milton Pharmacy, the drugstore and general store that her parents owned and ran in Rankin.

“In addition to selling meds, the store was also a mini post office,” she wrote in response to the story. “There was a busy soda fountain. There was a jewelry case and a section that held purses for sale. ... I especially remember selling lots of flash bulbs on the holidays.”

There was a bank across the street, she said, and a physician’s office nearby, plus pool halls, restaurants and busy numbers runners. “In my memory,” she wrote, “a very happy well integrated place to live.”

There’s still a friendliness about the place, and well-attended events like the annual holiday gathering at the borough building. Last year, though, many of the biggest gatherings were tinged with sadness and anger, as residents repeatedly protested the death of Antwon Rose II, who lived in Hawkins Village but died in June, at age 17, when he was shot by East Pittsburgh police Officer Michael Rosfeld, who faces a homicide charge.

Antwon’s mother, Michelle Kenney, wrote in response to Growing up through the Cracks: "The world needs to know what the kids are up against. Hopefully it will force someone or some group to take action."

[This story was originally published by the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.]