Danger: Learn at your own risk

This story was originally published in The Inquirer with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

Heading home from Watson Comly Elementary are (from left) father David Pagan holding Eliana, Johan, mother Cristine Pagan, and Dean. Dean said he ate paint chips that had fallen on his desk because he was afraid of getting in trouble for getting up to throw them out. He was hospitalized and treated for lead poisoning. (Photos by Jessica Griffin/The Inquirer)

By Wendy Ruderman, Barbara Laker, and Dylan Purcell

Many Philadelphia schools are incubators for illness, with environmental hazards that endanger students and hinder learning.

Day after day last September, toxic lead paint chips fluttered from the ceiling of a first-grade classroom and landed on the desk of 6-year-old Dean Pagan.

Dean didn’t want his desk to look messy. But he feared that if he got up to toss the paint slivers in the trash, he’d get in trouble.

So he put them in his mouth. And swallowed them.

It wasn’t until Dean was hospitalized last November for severe lead poisoning that the School District of Philadelphia grew alarmed enough to finally fix the chipping and peeling paint in Room 202 at Watson Comly Elementary in Northeast Philadelphia.

It came too late. Dean lost his ability to do simple math, such as adding three plus three in his head, calculations that once came easily to him, his parents said.

“When you send your child to school, you think he’s going to be safe and you don’t have to worry,” his father, David Pagan, said.

Every school day in Philadelphia, children are exposed to a stew of environmental hazards, both visible and invisible, that can rob them of a healthy place to learn and thrive. Too often, the district knows of the perils but downplays them to parents.

As part of its “Toxic City” series, the Inquirer and Daily News investigated the physical conditions at district-run schools. Reporters examined five years of internal maintenance logs and building records, and interviewed 120 teachers, nurses, parents, students, and experts.

When the newspapers analyzed the district records, they identified more than 9,000 environmental problems since September 2015. They reveal filthy schools and unsafe conditions — mold, deteriorated asbestos, and acres of flaking and peeling paint likely containing lead — that put children at risk.

Even so, the district often takes months, even years, to complete repairs, the investigation found.

Mold in Kindergarten classroom A-2 at Farrell Elementary.

To independently determine potential health hazards facing students, reporters enlisted staffers at some of the district’s most rundown elementary schools to conduct scientific tests for toxins.

In all, staffers at 19 schools, following testing guidelines, used surface wipes to sample areas for lead dust, mold spores, and asbestos fibers. They also collected water from drinking fountains. The newspapers used a nationally accredited lab to analyze the samples.

A disturbing picture emerged.

Dangerously high levels of cancer-causing asbestos fibers were found on surfaces in classrooms, gymnasiums, auditoriums, and busy hallways — residue from crumbling pipe insulation, damaged floor tiles, and deteriorating ceilings.

Tests revealed lead dust, at hazardous levels, on windowsills, floors, and shelves in classrooms, including one for children with autism.

School district officials took issue with the newspapers’ testing. They questioned the collection methods, and argued that air monitoring for asbestos — not dust wipes — is far more accurate and the only testing method required by law.

As for building conditions, district officials said they are saddled with too many old, deteriorating schools and too little money. It will take $3 billion over the next 10 years to build new schools, replace roofs and heating systems, and finish all urgent repairs, they said.

School officials also cite their inability to fill vacancies in custodial and maintenance staff and hire enough tradespeople to maintain the buildings. (The district recently started a program in which graduates of its vocational high schools will be hired as apprentice plumbers, electricians and HVAC technicians.)

The district spent $69 million in fiscal 2017 on cleaning, maintenance and renovations.

Eileen Duffey, a longtime school nurse, said it would only take "a reasonable amount of money" to prevent children like Dean from getting sick. Families are required by law to send their children to school, she noted, so the district at a minimum should provide a healthy environment.

"We have to figure out how to get out of the mess we're in," she said. "And in no place is it more important to provide that environment than in the schools where we require them to spend the greatest portion of their lives."

LOWER STANDARDS FOR SCHOOLS

Philadelphia children are at particularly high risk for lead poisoning because more than 92 percent of the city’s homes were built before 1978, the year the federal government outlawed residential use of lead paint to protect people from “the unreasonable risk of injury.”

Young children are most susceptible to the ravages of lead, a potent neurotoxin that can permanently damage a child’s brain, reduce IQ, and cause behavioral problems. Whether inhaled in airborne dust or ingested, the heavy metal is unsafe even in minuscule amounts.

At least three-quarters of children in Philadelphia district schools are from low-income families. Poor children tend to have poor nutrition, lacking calcium and iron, making it easier for lead to be absorbed in the body. Once absorbed in bones, lead stays for life.

In 2012, concerned Philadelphia lawmakers made it illegal for landlords to rent homes with damaged lead paint to families with children ages 6 or younger.

Yet that same law doesn’t apply to the city’s schools, even though 90 percent of them were built before the 1978 ban. Many of the district’s 130,000 Philadelphia children spent their school hours in buildings with damaged lead paint.

No city, state, or federal laws require that district schools be free of lead hazards.

Since the district does not routinely test classroom floors and surfaces for lead contamination, reporters had staffers at 14 elementary schools follow an EPA-approved protocol to collect surface dust for testing. The results were startling:

A sample from a second-grade classroom floor at A.S. Jenks Elementary School in South Philadelphia tested at 1,100 micrograms per square foot — almost 28 times the federal hazard level for residential floors.

A sample from a second-floor hallway at J. Hampton Moore Elementary School, in Northeast Philadelphia, tested at 1,400 micrograms of lead per square foot — 35 times higher than the federal hazard level for residential floors. In the ceiling directly above was a gaping hole, since fixed.

One dust wipe sample from the floor of a classroom for autistic children at Olney Elementary School tested at 5,900 micrograms per square foot — almost 150 times the federal hazard level.

And at Henry H. Houston Elementary School in Mount Airy, one dust sample taken from a second-floor hallway tested even higher, 6,300 micrograms per square foot.

“It’s totally unacceptable,” said Jerry Jordan, president of the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers, which has nearly 12,000 union members.

“The conditions of our old buildings have been allowed to deteriorate,” he said. “It’s something that in no other profession would anyone put up with …. Yet we put children, who are there to learn, and teachers, who are there to teach, in buildings where it’s just, ‘We’ll get to it when we get to it.’ ”

School district officials say they are streamlining their record-tracking system to get a more up-to-date picture of problems that need to be fixed.

“We want to be proactive in identifying, assessing, controlling, and preventing environmental health conditions in our schools,” said Francine Locke, the district’s environmental director. “So we go above and beyond regulations when we collect data about dampness, mold, paint, and plaster damage.”

‘THEY TOOK ALL MY BLOOD OUT’

When Dean Pagan started first grade at Comly Elementary last September, Room 202 was filled with potentially hazardous deteriorating paint, and the district knew it.

Five months earlier, an environmental inspector noted that the classroom’s ceiling had 250 square feet of peeling paint, district records show. More than in any other Comly classroom.

In fact, by the district’s own maintenance and environmental records over the past three years, flaking and peeling paint needed to be repaired in at least 165 schools, 126 of them elementary schools.

As those first school weeks went by, Dean’s teacher found him to be increasingly hard to handle and talked to his parents about him.

Dean Pagan at the playground of his school, Comly Elementary. He was diagnosed with severe lead poisoning in November that left him unable to do simple math calculations that once came easily to him, his parents said.

Dean, who wears green-framed eyeglasses and dreams of becoming a science or math teacher, is eager to please and has always “been a little hyper,” his parents say.

He told them he tried to earn a “green,” not “red,” on his teacher’s behavior chart. Green was for good kids, the ones who stayed in their seats and didn’t talk out of turn.

But day after day, he was marked “red” and often came home crying. His mom, Cristine Pagan, said she took TV time away from him; she didn’t know what else to do.

“He’d say, ‘I tried. I tried. I don’t know what’s wrong with me,’ ” she said. “He was just constantly upset.”

By October, his parents noticed stark changes: Mood swings. Frequent stomachaches. Inability to finish sentences. Overwhelming sadness.

“I knew something was going on,” his mother said.

The Pagans took their son to a psychiatrist and a therapist. He was diagnosed with ADHD, which can be linked to lead poisoning.

The couple had no idea their son had been eating paint chips at school. “Three or four pieces a day, or five,” Dean would later say.

Then on Nov. 9, Dean’s teacher saw him put chips in his mouth and alerted a school counselor.

The ceiling above Dean Pagan’s desk at Comly Elementary before the flaking lead paint was fixed by the Philadelphia School District.

Dean’s mom was waiting for her son at his bus stop when the counselor telephoned and alerted her. He told her he wasn’t sure if the paint contained lead, but just to be on the safe side, she should get him tested, Pagan recalled him saying.

They did, and when their pediatrician saw the test results, he called the Pagans right away and said: “Go straight to the hospital.”

The level of lead in Dean’s blood was 46 micrograms per deciliter — nine times higher than the level at which doctors worry about permanent damage to the brain, which could include intelligence loss and learning disabilities.

At St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children, Dean spent the next three days getting chelation therapy, a treatment used in cases of severe lead poisoning. Doctors gave him Chemet, in pill form, which binds to metals in the bloodstream and helps the body rid itself of much of the lead.

Doctors monitored him closely and gave him IV fluids for dehydration.

“It was scary,” Dean recalled. “They took all my blood out … The needles hurt. The pills, I couldn’t hardly swallow them. They smelled bad. I didn’t like the shots.”

He cried in the hospital bed, blaming himself. “He’d say, ‘I’m so sorry, Dad. It’s my fault. I shouldn’t have eaten that,’ ” David Pagan said. “It was so sad.”

Meanwhile, Comly principal Kate Sylvester moved Dean’s classmates to another room.

In a Nov. 15 letter to parents, she told them a first-grade student had an elevated blood-lead level and “as a precautionary measure, students have been relocated out of the classroom the student was in while testing takes place and the source of lead is identified.”

“They made it sound like it was nothing,” Cristine Pagan said. “Reading the letter, if I didn’t know the situation, I would throw it away.”

The Philadelphia Department of Public Health, which is alerted to all cases of lead poisoning, first inspected the Pagans’ apartment to determine the source of the lead contamination.

Inspectors found only trace amounts of lead in two places, at a baseboard in the attic and at a baseboard on the stairs leading up to the apartment. “It wasn’t places he’d go,” his father said.

They visited the school next. There they found damaged and flaking lead paint all over Comly — on walls, floors, windowsills and pipes in at least 16 areas, including Room 202, district records show. It comprised almost 800 square feet.

Yet in a Nov. 21 letter sent home to parents, principal Sylvester wrote, “The classroom had some loose and flaking paint” and also suggested that the source of the lead may have come from the Pagans' home. She declined a request to comment.

Locke, the district’s environmental director, told reporters two months ago that district painters have cleaned up and painted over all the deteriorating lead paint, including the damage in Room 104 — where Dean attended kindergarten.

Why had Dean’s classroom sat seven months, including over the summer, without being fixed? “That’s a really good question,” Locke replied.

She explained that the district prioritizes repair jobs, tackling those areas with the worst and most extensive damage. Dean’s classroom wasn’t considered perilous because the damaged paint was on the ceiling, presumably out of reach, Locke said.

“Unfortunately, we didn’t get to that particular school because it was on a ceiling and not on hand level to small children,” she said.

Arthur Steinberg, head of the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers Health and Welfare Fund, said he found Dean Pagan’s horrific lead poisoning “frightening” because Comly is not high on the list of schools in desperate need of paint repairs.

“Comly is one of the least dangerous places,” Steinberg said. “So what’s going on in the rest of the schools?”

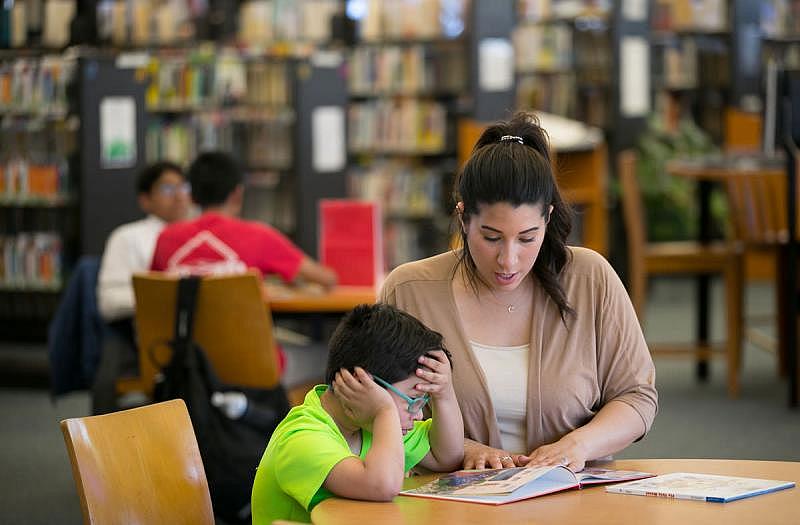

Cristine Pagan helps her son Dean with reading homework at a local library branch. When Dean started first grade at Comly Elementary last September, his classroom was filled with potentially hazardous deteriorating paint, and the school district knew it.

THE REMEDY? BUILD A NEW SCHOOL

Perhaps the most toxic school in the Philadelphia system is an elementary school in Overbrook called Lewis C. Cassidy Academics Plus.

Built in 1924, the austere, boxy building is one of a dozen Philadelphia schools that are so dilapidated it would cost almost as much to fix it ($25 million) as it would to raze it and replace with a new building ($30 million). Most of the 12 schools are in the city’s poorest neighborhoods.

Cassidy is one of the 19 elementary schools where reporters gathered evidence on conditions for scientific testing.

With one exception, the district’s own records reveal a sorry history that likely interfered with student learning: backed up sewage; leaking radiators; mouse droppings along chalkboard ledges and inside plastic lunch storage bins in several classrooms; mold in bathrooms, closets, and classrooms; 34 reports of flaking paint; 29 reports of damaged asbestos; 95 reports of asthma triggers such as mold, mice droppings and cockroaches, the list goes on.

However, all of the Cassidy drinking fountains tested under the limit for lead contamination, according to the records.

Some students at Cassidy were so upset by their school’s shoddy conditions that three fourth-grade classes wrote to their state representative last year pleading for help and funding.

They told of shivering in classrooms without heat and wearing winter coats to keep warm. They wrote of regularly seeing rats and mice in the lunchroom — even a cockroach spilling out of a milk carton. They said they’ve had to hang wet bookbags on the backs of chairs to dry out after a pipe burst. They’ve seen kids and teachers dodge debris that fell from a water-saturated classroom ceiling.

“Every day I go to school, I feel like I’m in a prison or a junkyard,” student Chelsea Mungo, then 10, wrote in a letter to her state senator, Vincent Hughes (D., Phila.).

Dayshin Oliver, then a fourth grader at the school, managed to share a glass-half-full observation: “Our schoolyard, it’s not that junky because we don’t have anything in it.”

Hughes visited the school last year and was alarmed by what he saw. "Your heart breaks,” he said.

Chelsea, now 11, seated on the couch with her father in their home, recently said of her school: “It’s just getting worse year after year.”

Teacher Valerie Williams worked at Cassidy from 1990 until she retired last June. "It was a horror story," she said. "Those children had no idea what a decent school looked like."

It wasn't until after the 2015 lead-contaminated water crisis in Flint, Mich. — and pressure from Philadelphia parents and students — that the district began to put filtered water fountains in schools, Williams complained.

The district's own testing from the 2016-17 school year showed that half of the elementary schools had at least one water outlet that measured for lead above 10 parts per billion (ppb), the district’s threshold for replacing fountains. To its credit, the district used a lower level than the EPA “action” guideline, which is 15 ppb.

Water from some of the fountains had lead at poisonous levels. A kindergarten classroom at North Philadelphia's John F. Hartranft Elementary School, for example, tested at 779 ppb. The district shut off all drinking fountains over its 10 ppb limit. Some water sources in kitchens and at bathroom sinks still have signs that warn “do not drink.”

At Cassidy, in 2016, 10 of its water taps were tested. The results ranged from 1.1 to 6.5 ppb, records show.

In a letter last August to parents of children at Cassidy, the district wrote: “At your school, all of the water outlets passed this stronger water safety threshold and the water is safe to drink.” (The EPA says, however, the only “safe” level of lead in drinking water is zero.)

A water fountain at Cassidy Elementary School that tested high for lead.

One of the drinking fountains deemed “safe” to Cassidy parents was a deep, oblong white basin with four spigots in a basement hallway across from the cafeteria and gym. Clusters of kids regularly lined up at the fountain during breakfast, lunch and gym.

On Jan. 2, the day teachers returned from winter break, a school employee took a water sample from that fountain for testing. The lab’s result came back at an alarming 44.6 ppb — more than four times the district’s limit.

Since the water sat in the lead pipes over the holiday, the newspapers gathered four samples at different times and days. Two were low. Two came back at 10.1 and 9.6 ppb.

A reporter immediately shared the results with the school district, which shut off the fountain by the next morning. Workmen later ripped out the old fountain and replaced it with a filtered “hydration station.”

Parent Dionne Battis said her daughter, Kymeisha, 10, a fourth grader at Cassidy, who has developmental delays and autistic spectrum disorder, often filled her water bottle from the now-replaced fountain. Her daughter takes medications that require her to drink a lot of water.

“Can you imagine all the kids that did drink from that water fountain?” Battis asked. “What about the kids’ [with] systems that can’t overpower the lead?” Battis asked.

Kenya Cannon, who works outside Cassidy as a crossing guard, said the school made her son, Basir, 11, sicker. He has asthma.

It wasn’t uncommon for Cassidy staffers to run out to her corner crossing and tell her Basir once again couldn’t breathe.

“I would just drop my stop sign and everything” and run and get him, she said. She would plug in the portable nebulizer she kept in her car and rescue him.

VENTS INFESTED WITH BACTERIA

Denise Garner and her 9-year-old daughter, Ashley, at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Ashley suffered a severe asthma flare-up that required a trip to the emergency room and a hospital stay in January.

Ashley Garner says she loves learning and makes A's and B's in her fourth grade class at Andrew Hamilton Elementary School in West Philadelphia.

But the district's Office of Attendance and Truancy has repeatedly contacted her mother, wanting to know why her daughter is missing so much school. So far this year, 9-year-old Ashley has been absent 44 days — all because of asthma.

Of the nation’s 25 most-populous cities, Philadelphia is the most challenging place to live if you have the life-threatening respiratory illness, according to one industry study. Asthma is the nation’s leading cause of student absenteeism and emergency room visits.

“We have to figure out ways to make schools more asthma-friendly,” said Tyra Bryant-Stephens, medical director of the Community Asthma Prevention Program at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

She is lead author of a study from 2012 that found more than 27 percent of Philadelphia school-age children suffer from asthma — nearly twice the national rate.

School officials said they are well aware of this problem and are supporting a National Institutes of Health asthma study and outreach at 20 schools in West and Southwest Philadelphia. Community health workers there will make sure children have their medications at school and use them properly, and also flag conditions that trigger asthma — mold, mouse droppings, and cockroaches.

This is little consolation to Ashley and her family.

Ashley says her asthma attacks feel like someone is sitting on her chest, choking her, and she panics as she gasps for her next breath. She rarely has flare-ups during the summer, her mother said. Until the last two months, her attacks typically took place at Hamilton Elementary. But her disease has worsened and she is now getting attacks at home, too.

Hamilton Elementary, like Cassidy, is also one of the 12 Philadelphia schools so rundown and deteriorated that it would cost nearly as much to fix them as to raze and replace them. The school is slated for a major renovation soon, including a new roof, school district officials say.

Until then, teachers and children are in a school that has a ventilation system lined with insulation infested with bacteria. It is too expensive to strip it all out, so the entire system must be replaced, records show. A district consultant labeled it a “potential liability problem.” In recent years, staff found 48 conditions that could trigger asthma, nearly all of them eventually addressed.

Three times this school year, doctors found Ashley in such distress that they admitted her to Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, according to family medical records reviewed by reporters. That doesn’t include the 15 times her mother, Denise Garner, took her to the emergency room.

Garner does everything possible to minimize asthma triggers in her world. She regularly vacuums, mops, and dusts her three-bedroom rowhouse in Southwest Philadelphia. She doesn’t smoke, nor do any visitors. And they have no pets.

But Garner loses all control the minute Ashley walks out the door to go to Hamilton.

“It’s exhausting. I cry. I get upset,” Garner said.

“It’s the worst thing in the world when there’s something wrong with your child — she’s sick — and there’s nothing I can do to fix it.”

As a single mom, Garner runs a daily road race. She works seven days a week at two jobs as a day-care worker and a home health aide.

Twice a year, the city's Health Department visits Ashley's school cafeteria.

In September 2016, health inspectors found numerous asthma triggers: fresh and old mice droppings, along with live and dead cockroaches on glue traps, in the food prep area of the cafeteria.

A year later, an inspector saw mouse droppings along the floor of the food prep and storage areas.

Although the most recent food inspection from January didn’t list rodent problems, Ashley says she sees cockroaches and mice scurrying around the school.

“I saw a mouse yesterday in the cafeteria,” she recently told a reporter. “It was near a table — two tables away from me on the floor. It was a gray mouse. I think it was dead. They swept it into a trash can.”

Her older sister, Erin, now 15, had asthma flare-ups only during the two years she attended Hamilton, her mother said.

Hamilton now has a nurse to give Ashley her inhaler, but Garner worries her daughter may not make it from the classroom to the nurse’s office two floors below.

“It’s scary,” she said. “My fear is that my child could die.”

‘WHAT IS DOWN THE ROAD?’

Cristine Pagan holds hands with her son Dean. She worries for his future. “I see it as sort of a time bomb,” Cristine Pagan said. “What kind of aftermath will there be?”

After Dean Pagan returned home from the hospital, school staffers sent him a get-well-soon card and a fruit arrangement of strawberries, pineapples, and melons cut into the shape of flowers.

Dean’s parents wonder what the future holds for their son.

Every math problem he gets wrong, every sentence he struggles to finish, every tantrum, every fidget during a movie — is that just Dean being a normal first grader? Or is it the lead poisoning?

“I see it as sort of a time bomb,” Cristine Pagan said. “What kind of aftermath will there be? What is down the road?”

“It’s horrible because he’s a very intelligent and bright boy,” David Pagan said. “He already has hardships with being a little more hyperactive. But if this takes away from his mental abilities, that would be a horrible thing.”

Cristine and David Pagan didn’t want to send Dean back to Comly. But they couldn’t afford private school. And home schooling was not an option because they both have to work. David is a store manager and Cristine a customer-care representative.

They considered other Philadelphia elementary schools but their pediatrician told them it would be a gamble to move their son from Comly.

“He said, ‘Honestly, it’s the safest place because they did all that work, all that painting.’ If he went to another school, we wouldn’t know if that school had lead either,” Cristine Pagan said.

Dean, who turned 7 in March, is now back in Room 202.

While that room has been repaired, problems didn’t go away at Comly. In March, district environmental workers, along with Jerry Roseman, a consultant for the teacher’s union, were called back to Comly. They found a sagging, water-soaked ceiling in a bathroom inside an autism-support classroom. Scattered on the floor below: lead paint debris.

It was caused by a leaking radiator on the floor above, an issue that Comly’s building engineer had reported to the school district in December 2016.

Almost a year before Dean was poisoned.