Dependency Court Backlog Finds Many Los Angeles Children Still in Limbo

This story was produced by Jeremy Loudenback as part of a larger project for the 2020 California Fellowship, a program of USC Annenberg's Center for Health Journalism.

Other stories in this series include:

Families in Limbo: Coronavirus Hobbles Reunifications from Foster Care

For Foster Youth, Stability Is Even Harder to Find During the Pandemic

Illustration by Christine Ongjoco

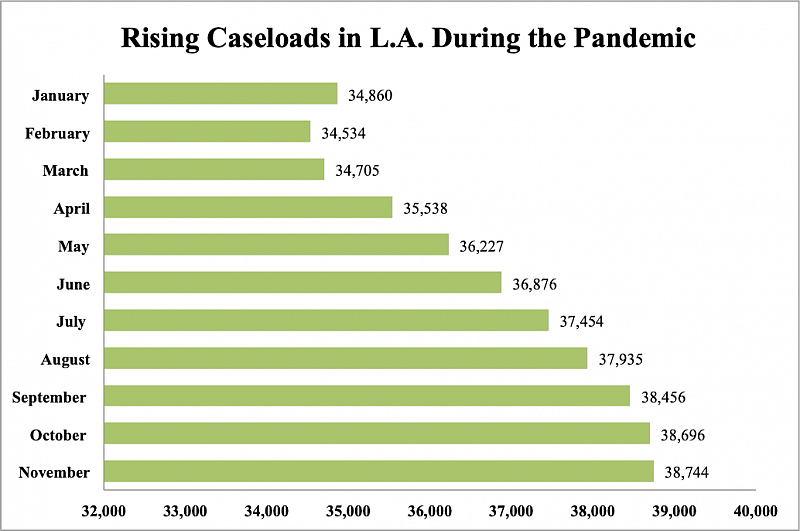

Since the coronavirus began to fray Los Angeles County’s safety net in March, the number of children involved with its child welfare system has swelled by 4,000 children, reaching the highest total in 14 years.

As the county’s dependency court grappled with how to safely continue operations during a pandemic, decisions made at the start of the emergency have resulted in thousands of children caught in the system, unable to get out.

Investigations into abuse and neglect proceeded through the spring and summer, as did removals into foster care. But the visitation and court hearings necessary to end child welfare cases were delayed for months, bloating the pipeline.

Interviews with attorneys, judges, public officials and parents of children in foster care show that many families have had their cases repeatedly delayed, extending time in the child welfare system and raising questions about their legal rights during hearings that have gone virtual.

Since the pandemic began in March, the most recent figures show that the number of children overseen by the Department of Children and Family Services has risen to 38,744, the highest since 2006.

“This number should disturb every single one of us who works in this system,” said Judge Michael Nash, director of the Los Angeles County Office of Child Protection.

Families’ poor access to technology and proper devices and lack of privacy have further hobbled the participation of children and parents in a legal process gone virtual. For those on a reunification path, visits have been suspended and court-ordered services made it difficult to complete. Meanwhile, dozens of adoptions — a path to permanent homes for some children in foster care — remain on hold.

“When you have so many barriers, it feels like your children are slipping away,” said Tanya, a Los Angeles-area mother who struggled to reunify with her children during the pandemic. The mom, 37, said she recently regained custody of her two young children, after being separated from them for nearly two years due to domestic violence and concerns about her behavioral health.

The Imprint is not fully identifying the Los Angeles mother to protect the identity of her children, who are back home but remain under the supervision of child protective services.

Over months, Tanya completed hours of therapy and parenting classes. But regular visits with her two kids, ages 3 and 6, were canceled, and at one point, she said she lost contact with them altogether.

Child welfare caseloads include both children who are placed into foster care as well as those living with their parents at home under the supervision of the Department of Children and Family Services. Source: DCFS

It wasn’t until June that Tanya was allowed to communicate regularly with her children on the phone or through video chats, and, had she not been so motivated to bring them home, she said, she fears she might have simply given up.

“Sometimes it’s easy to think, what’s the point?” Tanya said. “Maybe I should just start over.”

- - -

From March to June, Los Angeles’s courts were limited to hearing emergency matters only. Starting in June, the juvenile court restricted the daily number of cases each courtroom would hear and continued to prioritize hearings like removals. But even those cases are on a slow track, affecting children for whom every hour and every day can have a lifelong impact.

Earlier this month, the Superior Court’s supervising judge, Kevin Brazile, extended emergency guidelines in place since March; all children brought into the foster care system can be “detained” for up to a week without an initial court hearing to decide whether they can return home, instead of the usual 48 hours.

And while the court has allowed some children to enter foster care during the pandemic, the hearings for other ongoing child welfare cases that can lead to reunification and adoption have been delayed for months.

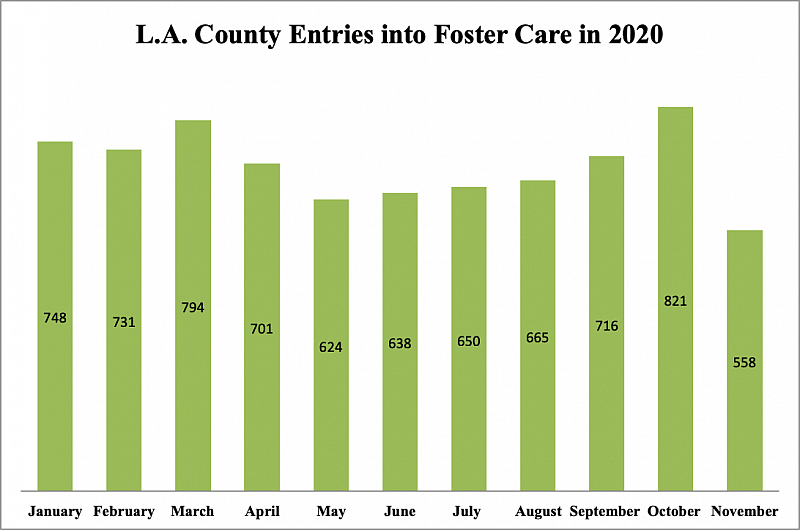

As a result, the number of children in foster care has grown during the pandemic. The total in November was 18,689, which is 923 more than February. Data shared with The Imprint by DCFS suggests that the cause is a combination of steady removals and sluggish exits, as well as the addition of a few hundred young people who have been able to remain in foster care after age 21 thanks to an order from Gov. Gavin Newsom.

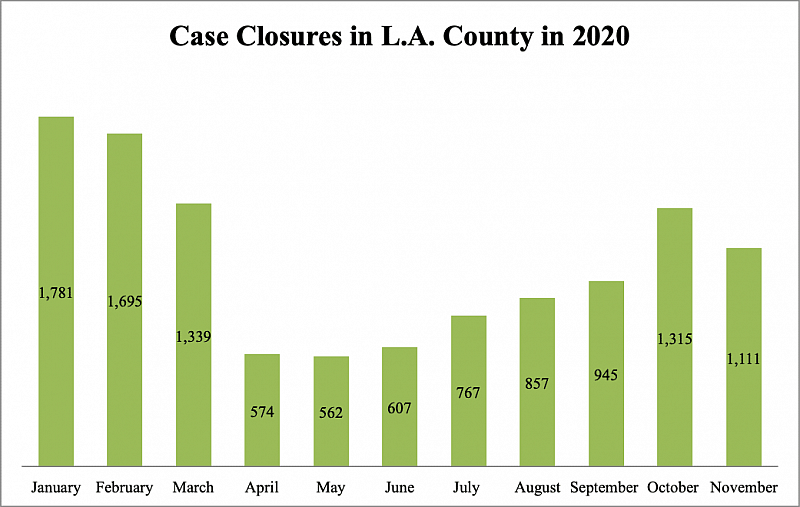

Source: DCFS

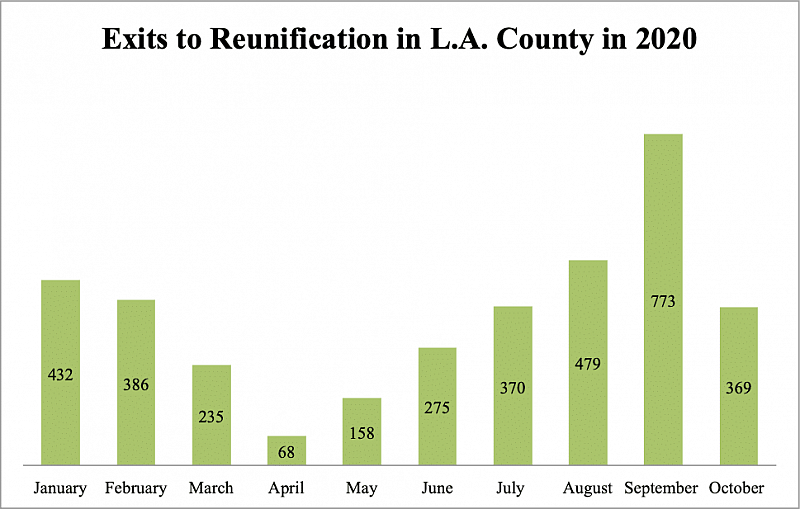

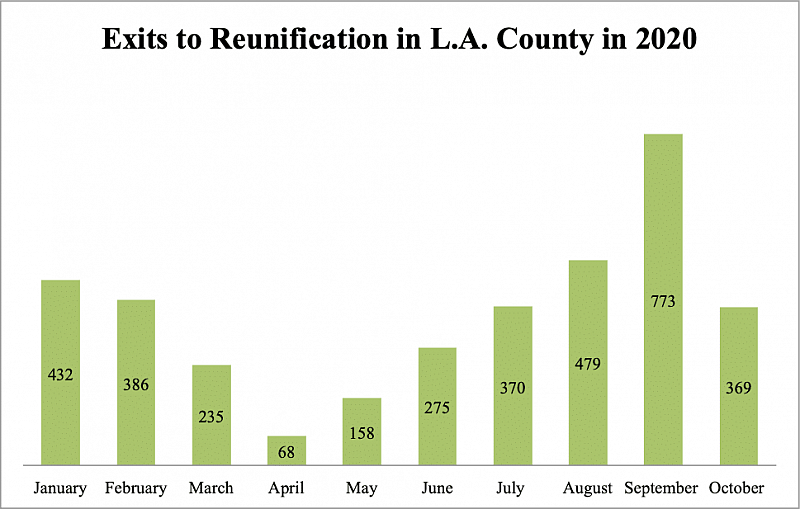

Source: DCFS

In January, 748 children entered the county’s foster care system. In May, that number had dropped slightly to 624 in May, before rising to 821 in October.

Reunifications from foster care dropped precipitously in April and have only rebounded in recent months as the county has been working to send more people home with their parents. Legal guardianships – another path to permanency for foster children – is still down by 80%.

The same pattern has emerged for families who are involved with DCFS but are not separated. In November, there were 38,744 children being supervised by the department in Los Angeles County, the highest total in at least 14 years, according to archived county documents. Before the coronavirus pandemic emerged in February, that number was 34,534. That 12.2% increase includes both children placed into foster care and those whose families are being supervised in their home by the department after a substantiated incident of child abuse or neglect.

As is the case with foster care exits, overall case closures have yet to catch up to the monthly pre-pandemic total of 1,781 in January. In April, the courts closed the cases of 574 children. By November, that number rose to 1,111, 38% below January.

The presiding judge of Los Angeles County’s juvenile courts, Victor Greenberg, declined to comment on the increasing numbers. But other Los Angeles County officials said they attribute the rise to the difficulty in closing cases — not to an uptick in abuse or neglect.

Another noteworthy peak occurred in July, when 2,156 children had been in foster care for 90 days or more without a required court hearing to determine the best path for their care and custody — more than four times the number of delayed cases prior to the pandemic. Those numbers are down considerably in recent months but remain higher than delayed cases before the pandemic.

Diane Iglesias, senior deputy director of the Department of Children and Family Services, said in an interview that parents accused of abuse or neglect are not to blame for the dramatic recent caseload growth in Los Angeles County.

“This is a reflection of the machine, rather than the family,” Iglesias told The Imprint.

- - -

On June 22, the dependency court began hearing cases virtually after it reopened, creating what some attorneys are calling the courthouse in the cloud.

But even after Judge Greenberg created a plan to establish foster care timelines for most hearings, the county’s 29 dependency courtrooms have been unable to match the pace and frequency required to properly process the families involved.

Late last month, the annual adoption day at the Edmund D. Edelman Children’s Court was held virtually for the first time. About 150 foster children were adopted, down from more than 200 last year. And even with 680 adoptions completed online through the end of October, there are still more than 1,000 adoptions left to be completed, a troubling prospect lengthening the limbo for these children.

Source: DCFS

The delays have left some caregivers not only frustrated with the ability to finalize the legality of their families but also unable to make some critical educational or medical decisions. In an article published in June by the Los Angeles Times, Stephanie Rivero and Ryan Cameron described the possibility of having to forgo a surgical procedure for their 5-year-old foster child who has a rare genetic disorder. “Having a child with significant medical needs and surgery coming up and not being able to make those important decisions for your child is heartbreaking,” Rivero told a reporter.

According to an informal poll of 36 medium and large counties in the state by the California Judicial Council, nine counties’ courts were completely closed at some point during the statewide stay-at-home order from March to May. Three more were partially closed.

Families’ hardships have been similar throughout California, judges and lawyers say: a reduction in face-to-face family time for court-ordered visits, trouble accessing technology and reliable Wi-Fi needed to attend virtual court hearings and general, systemwide delays.

Yet while at least seven court systems had backlogs after court closures, nearly all had reduced them by September, according to a staff member of the Judicial Council, the administrative arm of the state court system. Some counties caught up by working a month of double or triple calendars or progressively increasing dockets.

Los Angeles County — which accounts for about a third of the state’s foster care cases — has yet to catch up.

“The elephant in the room is L.A. County,” said 3rd District Court of Appeal Justice Vance Raye at a September meeting of the state’s Child Welfare Council, a group he co-chairs.

- - -

A disturbing offshoot is rising caseloads for attorneys representing parents and children — whose firms have not grown correspondingly as their cases have mounted.

“Kids are lingering and families are waiting. We are causing additional trauma and harm that can’t be undone later down the road,” said Leslie Heimov, executive director of the Children’s Law Center of California, which represents Los Angeles County foster children.

Heimov said that during the pandemic, caseloads of her Los Angeles lawyers have grown from 177 children per attorney to roughly 207 children, a setback for a decade’s worth of efforts to improve the quality of legal representation. Overburdened attorneys have less time to meet regularly with vulnerable youth and represent their interests in court.

For parent attorneys, the rising caseload has been even starker. Dennis Smeal, director of Los Angeles Dependency Lawyers, said his attorneys representing parents have also gained about 50 new cases and now manage more than 220 cases each.

According to a 2008 report from the Judicial Council, dependency attorneys should have a maximum of 141 clients to provide quality representation and 77 for optimal performance.

Parents have endured “wretched” timelines made even more challenging by the pandemic, Smeal said. With clocks ticking to make progress on their cases or face the permanent removal of their children, parents must complete court-ordered services like counseling, anger management and substance abuse classes, even when they’ve gone entirely online and completion is more challenging than ever.

Parents have also been denied or delayed in receiving approval for regular visits with their children. In other cases, visits have been scuttled because of transportation difficulties and a lack of personnel to schedule or monitor them during the pandemic, Smeal said.

In virtual court, there are still other challenges for the overwhelmingly low-income clients of dependency courts. Parents often lack computers, internet access and smartphones.

“When they just call in on a telephone line, and they’re struggling to be heard with the myriad other voices on the line, they don’t always end the hearing feeling like they’ve had their day in court, like they’ve been heard,” Smeal said.

Online hearings have also raised new questions about confidentiality in the highly sensitive issues hashed out regularly in the foster care courts. For example, when parents or children are being interviewed remotely during a court case, there is no way to know who else is listening, out of view of the camera. That might mean testimony influenced by an abusive family member nearby or details left out for fear of others overhearing.

At a recent public meeting, Heimov of the Children’s Law Center described a mother who had her parental rights terminated – the most powerful judgment that a dependency court can make, often referred to as the “civil death penalty” – during a phone call in her car, while she sobbed on the line.

“That’s inhumane,” Heimov said. “I don’t think that’s the kind of justice system we want.”

- - -

With court observers predicting backlogs in Los Angeles County’s juvenile dependency courts continuing well into the next year, the focus has shifted to how the system can improve its performance.

So far, lawyers have relied more heavily on more than 2,000 “stipulation agreements” between lawyers for the children, parents and the county that can achieve speedier resolutions than lengthy hearings. County records show that since the onset of the pandemic, 288 of these agreements involved children returned to parents under a supervision plan of some sort, and 744 where the family left the child welfare system altogether. But these cases, lawyers say, represent the easiest cases to resolve.

Source: DCFS

Los Angeles also launched night court on Dec. 8. For at least one day a month, the court will hold an extra session of dependency court from 5 to 7 p.m. Earlier this month, some judges used the extra time to get through several trials, while at least one judge helped close out the cases of some families who were unable to exit the system. In some cases, parents who did not complete all their counseling sessions during the pandemic or who were unable to get remote access to parenting classes were able to close out their cases in the absence of new allegations of abuse or neglect.

“Some judges seem to be recognizing that what looks good today may not have been enough to look good a year ago, but we don’t need to keep these people in the system when there’s not a real risk,” said Los Angeles Dependency Lawyers Executive Director Smeal.

In late September, Tanya’s key court date finally arrived. By that time, social workers had begun allowing her unmonitored visits with her children.

During the time they were apart, Tanya meticulously collected photos and videos of their sometimes joyful but at times difficult visits, when she realized how many developmental milestones she had missed. She also wanted to document the separation period, to one day show her two children that their mother never gave up on them.

One video shows the family together on the first night they spent back in her apartment. There was nervousness but also excitement at the prospect of life back together.

Before the Department of Children and Family Services stepped in, family dinners had always been vegan. So the mother of two prepared one of the children’s favorite meals — broccoli and rice — hoping the siblings would remember it.

This article was produced as a project for the USC Center for Health Journalism’s California Fellowship.

[This story was originally published by The Imprint.]