Gov. Tom Wolf’s plan to eliminate lead from Philadelphia schools faces opposition

This story was originally published in The Inquirer with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

Gov. Tom Wolf’s plan to eliminate lead from Philadelphia schools faces opposition

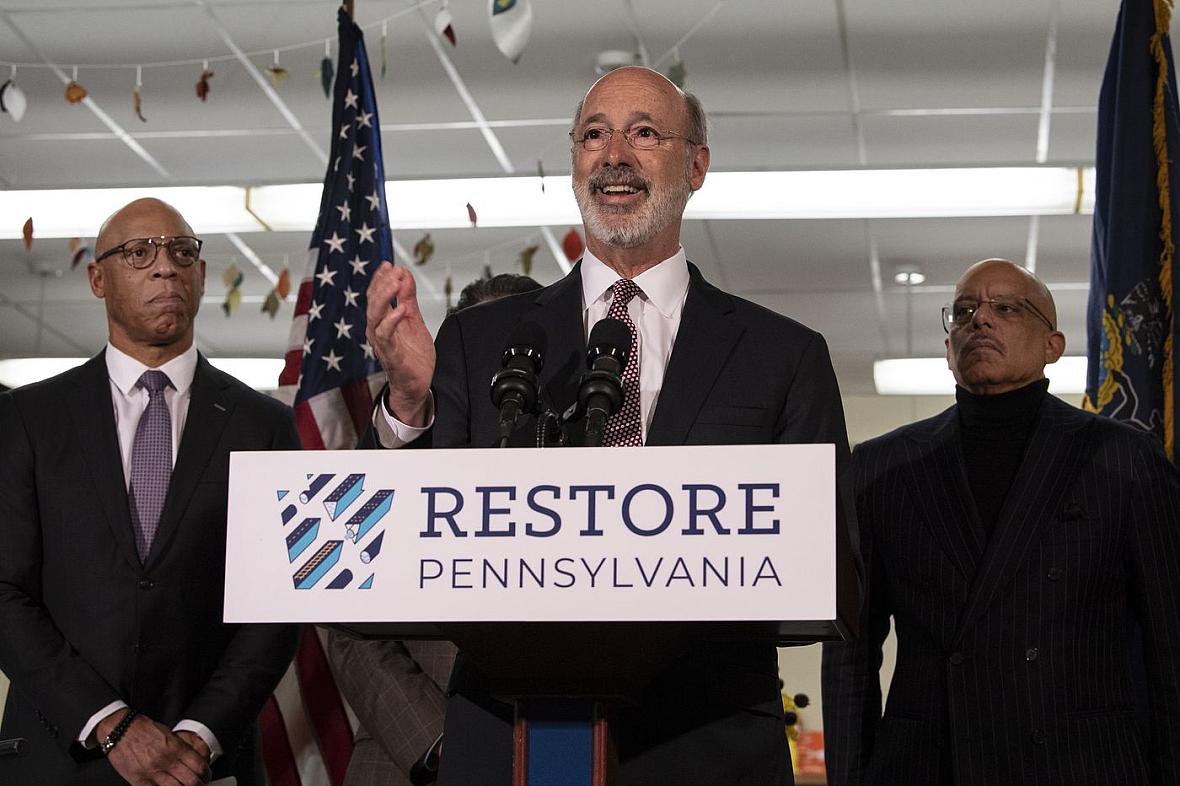

JOSE F. MORENO / STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER

Gov. Tom Wolf traveled to Taggart Elementary School in South Philadelphia to tout his proposed four-year, $4.5 billion Restore Pennsylvania initiative to fix crumbling schools, eliminate blight, repair storm damage, and expand high-speed internet across the state.

Wolf estimated it would cost $100 million to repair and remove lead paint and other perils in Philadelphia’s 200 aging district schools. He said he wants to fund the initiative with “a modest severance tax” on natural gas extraction. The Republican-led Assembly would have to approve such a tax, which historically has been a tough sell in Pennsylvania.

The governor said his push to find more money to fix Philadelphia schools came in response to The Inquirer’s 2018 “Toxic City: Sick Schools” investigation, which revealed how children got sick from environmental hazards, including lead paint, in their classrooms.

“When we go out to schools like this one that have problems with lead paint chips falling on the desks of students, when we get the question, ‘What are we going to do about it?’ — instead of saying, ‘There’s nothing I can do about it,’ we can say, ‘Here’s what we are going to do about it.’”

The newspaper’s investigation revealed the case of Dean Pagan, who was 6 when he ate lead paint chips that fell on his desk in his first-grade classroom at Watson Comly Elementary in Northeast Philadelphia. He was hospitalized with a blood-lead level nine times higher than the amount at which doctors worry about permanent brain damage.

To uncover health hazards, reporters enlisted staffers at 19 of the district’s most rundown elementary schools to conduct scientific tests for toxins. Tests revealed lead dust, at hazardous levels, on windowsills, floors, and shelves in classrooms.

In response, Wolf directed $15.7 million last June for emergency cleanup to repair lead paint and other hazards in more than 40 schools, a move to safeguard 29,000 children. Of that, $7.6 million came from a state grant, with the rest from the Philadelphia School District’s capital budget.

Taggart Elementary, a K-8 school in South Philadelphia built in 1916, was one of the 40. When district workers assessed the damage inside Taggart, they noted 17,400 square feet of damaged paint and plaster in almost 600 different areas, including classroom walls and ceilings.

The repair work at Taggart is expected to be completed in April.

After the series, Philadelphia enacted a law that requires school district officials to annually certify their buildings as “lead safe,” and be subjected to outside inspections, mandatory cleanup deadlines, and potential fines.

For years, lead paint dangers were widespread in Philadelphia’s public schools. Roughly 80 percent of the district’s schools were built prior to the 1978 ban on lead paint.

“There’s still a significant amount of work to be done. That’s why we’re advocating for a reliable source of funding,” said school superintendent William R. Hite Jr.

Since publication of the investigation, the School District of Philadelphia has completed lead repairs at eight schools — A.S. Jenks, Barton, Emlen, Finletter, Jackson, Kirkbride, Logan, and Nebinger. Lead cleanup is ongoing at Taggart and nine other schools. By summer’s end, about 17,000 students at 30 schools will have safe and clean learning spaces, the district said in a news release Thursday.

State Sen. Vincent Hughes (D., Phila.), who has made school conditions one of his signature issues, said he and other legislators have demanded a severance tax on natural-gas drilling companies for years. “This is an industry that has not given its fair share,” Hughes said Thursday. “It’s a modest assessment."

Pennsylvania is the only major gas-producing state without a severance tax.

The Marcellus Shale Coalition, a group representing the natural-gas industry, says drillers in Pennsylvania pay an “impact fee” that the legislature approved in 2012. Since then, the group says, Philadelphia and its four surrounding counties have received almost $54 million in such fees.

“Imposing additional energy taxes will cost consumers, hurt local jobs, especially among the building and labor trades, and negatively impact investment needed to safely produce clean and abundant energy that’s ushering in a new era of manufacturing growth,” Marcellus Shale Coalition president David Spigelmyer said in a statement Thursday.

Mike Straub, spokesperson for the House Republican Caucus, and Jennifer Kocher, spokesperson for the Republican Senate Caucus, both said their members support more money for fixing schools and roads, but believe it should not be funded by a new severance tax.

Wolf has said that the tax would generate $300 million per year that would be used to pay down about $4.5 billion in bonds.