Growing up through the Cracks: Pa.'s fix for distressed communities hasn't worked for Duquesne's families

This story was produced as part of a larger project led by Rich Lord, a participant in the USC Center for Health Journalism's 2018 Data Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

Charges lodged in North Braddock arrest

Growing up through the cracks: The children at the center of North Braddock's storm

Where fighting poverty is a priority

Pittsburgh's neighborhood boosters face changing landscape

Current and former Rankin residents remember the past, envision the future

Rankin, Pennsylvania: Fighting 'the depressed mindset'

Growing Up Through the Cracks: Mapping Inequality in Allegheny County

A mother moves from McKeesport to Glassport to try to better her family’s chances

Growing up through the cracks: North Braddock: Treasures Amid Ruins

Saltlick: “They don’t know they’re poor.”

Pa. officials reverse course on local family support center funding

What it’s like to work in child care, raise your kids and just get by in the Mon Valley

Study: An increasing number of Pa. kids living in high-poverty areas

Stephanie Strasburg/Post-Gazette

By Kate Giammarise

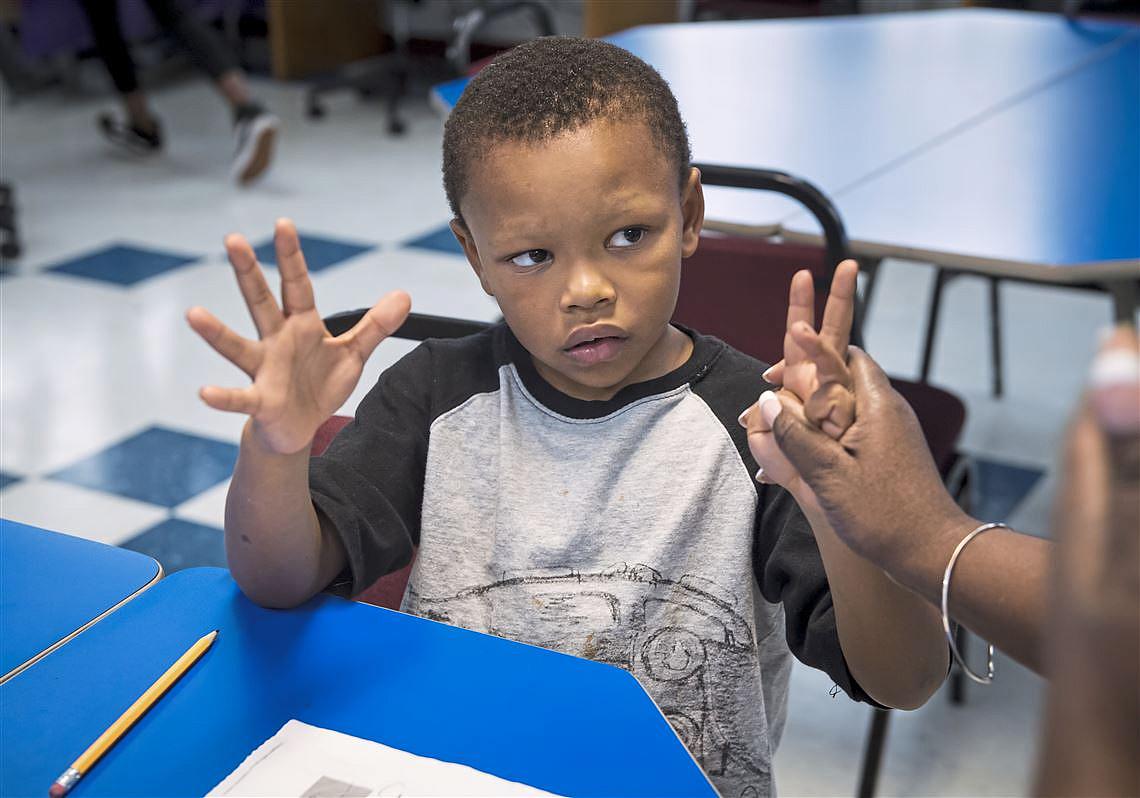

Every weekday after school, dozens of children pour into a repurposed former Serbian Club on North Third Street in Duquesne.

The walls of the Duquesne-West Mifflin Boys & Girls Club are decorated with cheerful slogans: “The Positive Place for Kids!”

“The Club That Beats the Streets!”

“Great Futures Start Here.”

They are a small counterweight to the reality that the city has one of the highest child poverty rates in the region and services are few.

Here, kids play at the air hockey or foosball tables, talk to their friends, do their homework, or have a hot meal in the basement. Staff tell them to keep their voices down when they get too loud.

Though it maintains parks, the city offers no recreation programs, so the Boys & Girls Club is a magnet for youngsters after school and during the summer.

It’s an island of affirmation surrounded by signs of problematic futures. And the one thing the state offers to turn things around — Act 47, for “financially distressed” municipalities — hasn’t done the trick for the city of 5,500, despite decades of oversight. A new plan, expected to be approved by city officials next month, calls for continued spending limits and a more coordinated approach to development.

About half of Duquesne’s kids live in poverty.

About a third of its residents use county human services.

Its real estate is among the lowest taxable value per-person countywide.

Like its families, the challenges facing the small city of Duquesne are extraordinary. But the tools it has are few, and mismatched to solving its financial problems, many experts believe.

In Growing Up Through the Cracks, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette is examining how concentrated child poverty harms kids, families, and communities.

Duquesne is one of seven Allegheny County municipalities in which half of or more of the kids live in poverty. The others are North Braddock, Mount Oliver, Rankin, McKeesport, Clairton and Wilmerding.

Rankin is also in Act 47. Clairton and North Braddock were in Act 47 previously but exited the program.

State-appointed Act 47 coordinators are very good at helping municipalities with management issues, said Karen Miller, a former state official who helped to oversee the program when it was first created.

“But they can't create a healthy economic environment,” she said.

‘Distressed’

While most human services are provided through county government, municipal governments are responsible for a host of roles that can greatly impact a place’s quality of life — such as police and public safety services, local parks, and dealing with vacant and abandoned properties.

Citizen concerns at recent city council meetings involved vacant buildings in the community, issues with water billing, problems with trash pickup and streets not being properly cleared during snowy weather.

Resident Shonna Partlow attended one such meeting last month with her two young children to ask questions about the city's Act 47 exit plan and about how it would affect her family.

“I basically was trying to figure out if I was going to stay in Duquesne,” she said later, adding she has concerns about taxes, crime and schools there.

Duquesne is designated by the state as “distressed” under Act 47, a label it has had since 1991.

Under Act 47, a state-appointed coordinator assists the city with a recovery plan. The city is also able to levy certain taxes it otherwise could not, and it can tax non-residents who work in the community.

Council members are expected to vote soon to approve a plan for the city to exit Act 47 status by 2022.

The city’s prior Act 47 plan lays bare its starkest and principal challenge: Duquesne must attract new businesses and residents to grow its tax base, which has steadily eroded for decades. But it is unlikely to do that without improvements to its school system. And, in a municipal governance Catch-22, it is unlikely to be able to improve its schools without growing its tax base with new residents. The school district has been in state receivership since 2013. It has an elementary school, but high school students attend neighboring districts.

“There's nothing in these municipalities that a really good tax base couldn't solve,” said George W. Dougherty, Jr., Act 47 coordinator for both Duquesne and Braddock, which has also been in the Act 47 program for decades.

Duquesne’s Act 47 plans dating back to the early 1990s have suggested a number of similar proposals for saving money, such as consolidating its police force with a neighboring community.

But Act 47 cannot compel other municipalities to do anything. A state coordinator can't force neighboring non-Act 47 communities to participate in any program with Duquesne.

The limits of the law

Some experts have long said Act 47 does not give places like Duquesne what they need.

While municipalities can get aid like technical assistance and some special taxing powers, the law does nothing to rebuild a badly eroded tax base or attract new residents or businesses to distressed communities, a 2017 report from the Pennsylvania Economy League noted.

The law “does little to fix the underlying causes of distress — a lack of available tax base that forces municipalities to dig so deep into those resources in the form of tax burden that it can become confiscatory; a large need and/or demand for public services; and underfunded or unfunded state rules and mandates,” said the Pennsylvania Economy League analysis.

The state, recognizing that many communities had been in Act 47 for decades, overhauled the law in 2014. One of the major changes legislators made was imposing a five-year deadline to leave the program, though municipalities can apply for extensions.

But experts say that change was inadequate.

“The truth is that the Commonwealth can change the optics of distress by claiming to have ‘fixed’ Act 47 municipalities by forcing them out of the program but that action has done nothing to repair the broken system these municipalities must operate in,” said the Pennsylvania Economy League study.

State officials say Act 47 helps bring in local government experts like recovery coordinators, as well as helping communities get access to low-interest loans.

“The biggest strength are the people we can bring to the table to help the local elected officials,” said Deputy Secretary for Community Affairs and Development Rick Vilello, who oversees the Act 47 program at Pennsylvania’s Department of Community and Economic Development.

Still, he acknowledged the challenges faced by places like Duquesne and the shortcomings of the law. “We have to live with the legislation that we have, not the one we wish we had,” he said.

Ms. Miller was the state’s secretary of community affairs when Act 47 went into effect in 1987 under Gov. Bob Casey Sr. (Community Affairs was the forerunner to the Department of Community and Economic Development, which oversees the Act 47 program).

The steel industry was collapsing in Western Pennsylvania, and the new law was supposed to help communities deal with what were enormous blows to their local tax bases.

Duquesne’s population was already in decline when the U.S. Steel Duquesne Works shut down in 1984.

The law aimed to aid communities in fixing their management issues and help cities recover economically, said Ms. Miller, now senior fellow at Berks Community Foundation in Berks County. The law did little to help communities explore or emphasize shared services, she noted.

Melvin Peterson of Homestead separates recycled polyester used for pillows. (Michael M. Santiago/Post-Gazette)

Even in Act 47, communities are still constrained by their physical boundaries, said Juliet Moringiello, a professor at Widener University in Harrisburg and an expert on municipal bankruptcy.

“What they need to be doing, really, is combining with other municipalities,” but municipalities can't do this unless the voters of both jurisdictions agree to it, she said.

“It doesn’t surprise me much that you are seeing a correlation between child poverty and these distressed communities,” said state Sen. John Blake, D-Lackawanna.

Mr. Blake represents Scranton, which has been in Act 47 since 1992. He was heavily involved when the legislature updated the law in 2014.

“I think that there are structural problems in some of these communities that lend themselves to fiscal distress. Part of it is archaic tax policy. ... The other thing is you have economics and demographic changes that are beyond the control of local government officials.”

A former DCED official, Mr. Blake is also critical of the state for spending far less on community redevelopment than it used to prior to the Great Recession.

“If cities have blight, or brownfields, or leftover industrial sites, we’re not as aggressive at putting that to good use,” as the state used to be, he said.

At Duquesne’s former mill site, which once employed thousands of steelworkers, about 700 people are now employed at a mix of companies, from entry-level posts to highly trained engineering jobs.

The site is just over half developed, said Timothy White, senior vice president, development for the Regional Industrial Development Corporation of Southwestern Pennsylvania, which controls the site, and is in talks to attract other companies, he said.

It’s unclear exactly how many Duquesne residents work there. At American Textile, a pillow and bedding manufacturing company that has 280 employees on the site, approximately 45 live in Duquesne, according to company officials.

An exit plan

Recent Duquesne council meetings have been marked by tension between Mayor Nickole Nesby and City Treasurer David Bires. There have also been disagreements with the prior administration; the city last year sued its own nonprofit redevelopment authority and the Duquesne Business Advisory Corporation, which is controlled by former city officials.

Nevertheless, council members are expected to unite around the exit plan.

Along with a number of measures to control the city’s costs, Duquesne’s Act 47 exit plan calls for marketing development in the city’s state-designated “Keystone Opportunity Zones,” coordinating with the county’s economic development department, exploring options to further develop the former mill site, preparing a redevelopment plan for the former Cochrandale site (a large tract of land that once held public housing and is now vacant), and that the city work to allow riverfront access for city residents.

“We know that it’s a challenge and adopting the exit plan is important,” said Mr. Vilello, who oversees Act 47 for the state. “We’re not going to go away, we’re going to work through the exit plan and be partners all through the process. ... We’re committed to helping Duquesne succeed.”

It may not be enough for residents like Ms. Partlow, who said she would like to leave Duquesne, after an attempted break-in at her home.

“I would like to move,” she said. “That never would have happened to us in Penn Hills.”

Kate Giammarise: kgiammarise@post-gazette.com or 412-263-3909. This story was produced with assistance from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s Data Fellowship.

[This article was originally published by the Post-Gazette.]