Hawaii Pacific Islanders Are Twice As Likely To Be Hospitalized For COVID-19

This article is part of a larger project by Anita Hofschneider, produced with support from the 2020 National Fellowship and a grant from the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism.

Her other stories include:

Community Leaders: State Is Failing Pacific Islanders In The Pandemic

Hawaii's Pandemic: Hardest Hit Communities Part 1: Hawaii Wanted To Save Insurance Money. People Died

Hawaii's Pandemic: Hardest Hit Communities Part 2: Health Officials Knew COVID-19 Would Hit Pacific Islanders Hard. The State Still Fell Short

Hawaii Researchers: State Must Support Pacific Islanders In The Pandemic

Pacific Islanders Have The Highest COVID-19 Death Rate In Hawaii

Women Were Already Struggling At Work. The Pandemic Is Making It Worse

Here’s What Honolulu Is Doing To Test Hard-Hit Communities For COVID-19

Kalihi Has The Worst COVID-19 Outbreak In Hawaii. Here’s How The Community Is Responding

Hawaii COVID-19 Data For Race And Ethnicity Is Missing

Hawaii's Pandemic: Hardest Hit Communities Part 3: Pacific Islanders Can’t Return Home During COVID-19 — Even To Bury Their Loved Ones

Hawaii's Pandemic: Hardest Hit Communities Part 4: The Pandemic Is Hitting Hawaii’s Filipino Community Hard

Honolulu Civil Beat

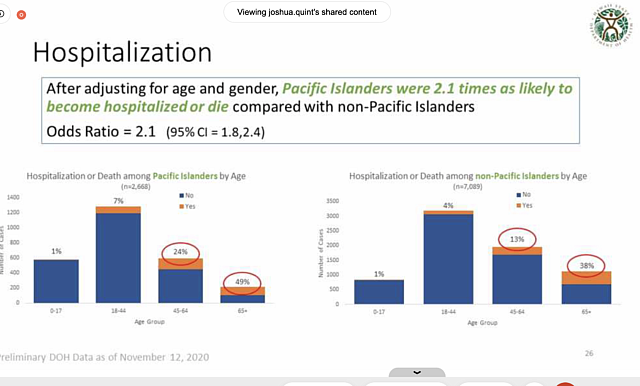

Pacific Islanders, excluding Native Hawaiians, are more than twice as likely to be killed or hospitalized by the coronavirus in Hawaii than other racial and ethnic groups after adjusting for age and gender, according to newly released data from the state Health Department.

The agency presented data on how some racial groups in Hawaii are being unevenly impacted by the virus during a hearing with Hawaii’s advisory group to the U.S. Civil Rights Commission live-streamed Wednesday. This was the first of three planned hearings on Pacific Islanders and COVID-19 for a report the group plans to publish next summer.

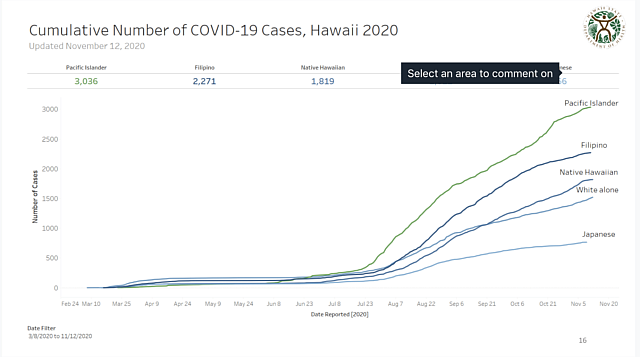

Joshua Quint, an epidemiologist at the department, cautioned that there’s a lot of missing data about race as the state has a backlog of cleaning up data for cases, particularly from August. But based on the data that is available, Quint said non-Hawaiian Pacific Islanders are at a five-fold risk of getting COVID-19 compared with Filipinos, who are the only other ethnic group in Hawaii contracting the virus at disproportionately high rates.

This graphic shows the COVID-19 hospitalization rates for Pacific Islanders in Hawaii as of Nov. 18, 2020.

As of Nov. 12, Hawaii’s non-Hawaiian Pacific Islander community had more than 3,000 coronavirus cases, nearly twice as many as the state’s white community and four times as many as the Japanese community, both of which have much larger populations.

“The disparity is truly stark,” Quint said.

He noted that based on a small sample of cases, Pacific Islanders who have gotten COVID-19 in Hawaii are more likely to be female; more likely to have diabetes; more likely to be unemployed; and more likely to come in contact with more than three people while sick. They’re also more likely to be under 18 years old, which Quint noted may partially be due to crowded housing conditions.

While as a whole Hawaii’s Pacific Islander communities are experiencing high coronavirus rates, some are more affected. The Chuukese community by far has had the most coronavirus infections, followed by Marshallese and Samoans.

Access to health insurance while unemployed varies widely amongst Pacific Islanders. Hawaii residents from Chuuk or the Marshall Islands haven’t been eligible for federal Medicaid since 1996, and Gov. David Ige cut their access to state-funded Medicaid in 2015.

Chamorros from Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands are U.S. citizens and are eligible for Medicaid and other federal programs. Samoans who are U.S. nationals have access to Medicaid as well, but Samoans from the country of Samoa have to live in the U.S. for several years before they can enroll.

Improved State Response

Back in April, Bruce Anderson, then-director of the Hawaii Department of Health, said he didn’t expect to see racial disparities in Hawaii’s pandemic. Former state epidemiologist Sarah Park upset Pacific community advocates after appearing uninterested in adopting their recommendations to stem the spread in their communities.

Anderson retired and Park was placed on leave in the wake of widespread criticism of their handling of the pandemic. Hawaii’s new health department leadership seems much more concerned about the pandemic disparities.

Sarah Kemble, acting state epidemiologist, said the uneven impact of the pandemic underscores existing health inequities in Hawaii. Emily Roberson, chief of the disease investigation branch, said that social determinants of health — such as discrimination, health insurance status and housing situation — should be an integral part of emergency response.

Here are Hawaii’s COVID-19 cases by race depicted over time.

Quint noted that the department considered a lot of different factors before disaggregating data, including concerns about how more specific information might exacerbate discrimination and the need for information to better target resources.

Roberson said the department has been participating in meetings held by a grassroots Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander task force formed in response to the pandemic. In August, the agency formed a Pacific Islander priority investigations and outreach team to help with contact tracing, investigations and case monitoring. The state prioritized linguistic skills, cultural knowledge and community recommendations when choosing staff, she said.

More Can Be Done

Participants in the meeting praised the state’s improved response but said more needs to be done. Wilfred Alik, a Marshallese physician, noted a task force formed by the Marshall Islands consul general created in the spring has been helping patients on a volunteer basis and there’s a need for the department to hire staff on Hawaii island.

“We need people in the community to be part of the solution,” he said. “We’re willing to help, the problem is we don’t have any resources.”

Nationally, lack of data about Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islander communities continues to be a problem as many states ignore federal guidance about separating Pacific communities from Asian Americans and other racial groups. Researchers from the University of California at Los Angeles who presented at Wednesday’s hearing said the most affected Pacific communities in California are Tongans, Samoans and Marshallese. They noted the way Hawaii differentiates these communities in its data instead of lumping them together may be a model for other states.

“If a community doesn’t exist in the data, it doesn’t exist in the eyes of policymakers,” said researcher Richard Chang.

The U.S. Civil Rights Commission advisory group is planning another hearing about pandemic disparities in December.

[This story was originally published by Honolulu Civil Beat.]