Women Were Already Struggling At Work. The Pandemic Is Making It Worse

This article is part of a larger project by Anita Hofschneider, produced with support from the 2020 National Fellowship and a grant from the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism.

Her other stories include:

Community Leaders: State Is Failing Pacific Islanders In The Pandemic

Hawaii's Pandemic: Hardest Hit Communities Part 1: Hawaii Wanted To Save Insurance Money. People Died

Hawaii's Pandemic: Hardest Hit Communities Part 2: Health Officials Knew COVID-19 Would Hit Pacific Islanders Hard. The State Still Fell Short

Hawaii Researchers: State Must Support Pacific Islanders In The Pandemic

Pacific Islanders Have The Highest COVID-19 Death Rate In Hawaii

Here’s What Honolulu Is Doing To Test Hard-Hit Communities For COVID-19

Kalihi Has The Worst COVID-19 Outbreak In Hawaii. Here’s How The Community Is Responding

Hawaii COVID-19 Data For Race And Ethnicity Is Missing

Hawaii Pacific Islanders Are Twice As Likely To Be Hospitalized For COVID-19

Hawaii's Pandemic: Hardest Hit Communities Part 3: Pacific Islanders Can’t Return Home During COVID-19 — Even To Bury Their Loved Ones

Hawaii's Pandemic: Hardest Hit Communities Part 4: The Pandemic Is Hitting Hawaii’s Filipino Community Hard

Female small business owners have been disproportionately affected by pandemic shutdowns.

Elizabeth Asuega doesn’t want to stop working at the Department of Human Services. But because of the pandemic, she’s worried she might have to — at least temporarily.

Asuega, 39, has been a secretary at the state agency for about five years. Normally, she goes into the office five days a week. But now she needs to be home with her three elementary school-aged children while they take classes virtually.

She hasn’t been able to get approval from her supervisors to work remotely full time, or to shift her schedule to the late afternoons or evenings.

“They’re not supporting me or helping me,” she said.

Asuega might feel alone, but she’s far from it. The COVID-19 pandemic is exacerbating long-established gender inequities in the workplace.

Women in Hawaii’s workforce are leaving in droves, with thousands more filing for unemployment compared with men. Experts say that’s because the industries hit hardest by the pandemic in Hawaii are dominated by women, while more unaffected industries like construction are male-dominated.

So far, more men than women in Hawaii have gotten sick from the coronavirus and more than twice as many men have died from the virus — 33 compared with 15, according to the latest available breakdowns. But women are more likely than men to be in jobs like teaching, nursing and caregiving, potentially increasing their exposure. And data suggests they’re more likely to be suffering financially due to the pandemic.

Between January and March, more men than women filed for unemployment in Hawaii. But after the pandemic shutdowns, between April and July, about 44,000 more women than men claimed unemployment insurance, according to the state Department of Labor and Industrial Relations.

Denise Konan is Dean of the College of Social Sciences and Professor of Economics at the University of Hawaii at Manoa.

In late July, federal survey data found Hawaii women were more likely than men to report missing a rent or mortgage payment or to expect to miss their next payment. Women were also more likely to report they didn’t have enough to eat, although hunger for both men and women was on the upswing.

A new survey by the University of Hawaii Economic Research Organization found that 17.7% of businesses owned by Hawaii women had shut down compared with 11.3% of businesses owned by men.

Many women who have been lucky enough to keep their jobs are also struggling to maintain them. The triple-digit daily coronavirus cases are prompting many schools to operate remotely, forcing parents like Asuega to scramble to figure out child care arrangements. A state survey of 59 women by the Hawaii Commission on the Status of Women found nearly 90% of single mothers surveyed struggled to balance work and caregiving.

Some women who are still employed are simultaneously worried about losing their jobs and getting sick on the job as they continue working in the service industry or other frontline positions.

Before the pandemic, Hawaii women were making just 83 cents compared with every dollar made by Hawaii men, says Denise Konan, an economics professor and dean of the University of Hawaii at Manoa College of Social Sciences.

“This pandemic is going to further erode the disparities that were already there,” she said.

The Risks Of Work

Kayla Keehu-Alexander is one of the thousands of Hawaii women who are now out of work. She just found out Thursday that she would be furloughed for the second time this year due to another pandemic-related shutdown.

Keehu-Alexander has been running a coffee shop at the Ala Moana Shopping Center for the past five years. Back in March, she was furloughed for three weeks. She feels lucky that she was quickly rehired, especially since she didn’t get her first unemployment check until she was back on the job.

Kayla Keehu-Alexander loves training and managing young people at a coffee shop in Ala Moana.

But being back at work wasn’t easy. She had to lay off nearly 30 employees, mostly women, and it was painful to let go of so many staffers who were relying on the job to support their schooling and livelihoods. She ended up rehiring four employees but had to furlough them again this week.

Part of her is relieved that the state imposed another shutdown. Her company has strict rules regarding mask-wearing and sanitation, but every once in a while a customer would refuse to wear a mask — inciting anxiety and sometimes reducing her employees to tears. One man who wasn’t wearing a mask yelled in her face after she told him the rules.

“Statistically speaking, the amount of people that come through, we’ve probably served someone with COVID,” she said.

But being out of work again comes with financial anxiety. Keehu-Alexander genuinely enjoys her job, and hopes that this shutdown only lasts two weeks. But the pandemic is making her wonder if she should try to find something different.

“It would be hard to leave something that I’ve put so much into for the last several years. It would be a big change but every day I’m starting to think it might be more and more inevitable,” she said. “I’ve been trying to prepare myself for the possibility.”

Not knowing what the future holds is stressful. She and her husband just bought a house and planned to start a family. She feels lucky her husband, who works in construction, seems to have a steady job but the uncertainty around hers makes her hesitant to have a baby.

“That’s a big question mark because we don’t know what the world will look like. It’s definitely something that we’re reconsidering,” she said.

Konan from UH says Keehu-Alexander’s experience is shared by many women in Hawaii.

“Women, they tend to be in service sectors, they tend to be in those kind of sectors that there’s an interaction with people that’s a key part of the job,” she said. “That becomes really hard in a pandemic where that interaction now is dangerous.”

Finding Support

Some women are relying on support networks to get them through the pandemic. Tiare Kaolelopono is a business owner who lives and works in Kaneohe. She suddenly had to stop selling her jewelry at craft fairs and move everything online.

It was jarring, but with help from the Council for Native Hawaiian Advancement, support from her church and advice from other Native Hawaiian business owners, she’s figured out how to promote her business online. Unlike many other small business owners, she isn’t struggling financially now.

“It’s like being pummeled by a wave,” she said of the pandemic. “You don’t know what is up and down.”

Her community has helped her surface, she said.

Tiare Kaolelopono started selling her jewelry online due to the pandemic.

That resilience is important, Konan said. But she added it’s also important that people in power support flexible work policies that help encourage women to remain in the workforce.

That’s what Asuega is struggling with. She has been able to work from home partially since March, but now that school is back in session and fully remote, that’s not enough.

She said she’s asked if her office could forward calls to her cell phone to no avail; if she could start work in the mid-afternoon after school ends; and if she could work at least three days from home, instead of two. She said she’s been told that she should go on leave without pay, but her family can’t afford that.

“I’m very stressed out,” she said. “For them to tell me to be on leave without pay is like, wow. I love my job. I love what I do.”

Amanda Stevens, a spokeswoman for the Department of Human Services, said that Asuega’s supervisor is trying to work with her to find a solution. Stevens said many DHS employees have been working remotely for multiple days, supervisors are encouraged to grant paid and unpaid time off, and decisions are made on a case-by-case basis.

“We are sensitive to the particular challenges DHS employees are facing, including decisions employees face whose children are normally in school or other child care during the work day,” she said. “The continuing impact of this pandemic presents many complex issues, so we need to be creative and flexible in finding ways to support employees and also continue to provide important safety net services.”

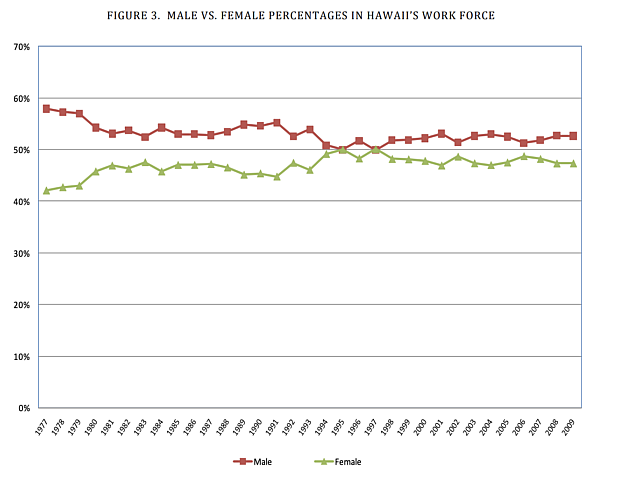

Here’s a graph showing women in Hawaii’s workforce over time, according to the state.

Khara Jabola-Carolus, executive director of the Commission on the Status of Women, has been sounding the alarm about how the pandemic is affecting women for months. She published a feminist economic recovery plan for Hawaii, and said since the pandemic started her office regularly hears from women in agencies ranging from the Department of Health to the state Judiciary who are struggling to get more flexible work policies.

The state’s return to non-emergency telework on July 1 has resulted in wildly varying policies, and put the onus on staffers to make the case for telework, rather than supervisors to prove why employees should remain in the office, Jabola-Carolus said.

A public information officer for Gov. David Ige said employees may telework if their children go to school remotely but that it’s up to individual departments and agencies to approve such requests.

The City & County of Honolulu doesn’t allow its workers to take care of their children while working remotely, according to a city spokesman. Non-essential workers may be eligible to take advantage of a federal leave program.

“An individualized approach to a system problem is causing a crisis and women to come and ask us to help,” Jabola-Carolus said. “This is a women’s rights issue. This is not just about being considerate to families.”

She wishes the state would “leave behind the obsession with the traditional workplace model.”

“It’s not rational in terms of saving money for the state. It’s not rational in terms of saving lives,” she said. “I think it has everything to do with gender roles and we’re in denial if we say the economic situation isn’t a reflection of sexism.”

Asuega said her Samoan family wants to help, but a language barrier and lack of familiarity with technology make it difficult for them to assist the kids with online school. Her children are in kindergarten, second grade and fifth grade.

Her husband works in construction and can’t do his work from home. Asuega said if she went on leave without pay, their family wouldn’t be able to afford their bills.

Jabola-Carolus said she hopes policymakers see that the pandemic is highlighting the importance of viewing policies through how they affect women.

“All of this could have been prevented. It could have been predicted and prevented,” she said. When it comes to workplace policies that support women and caregiving, “now we can see how central it is to our economy.”

“Hawaii’s Changing Economy” series is supported by a grant from the Hawaii Community Foundation as part of its CHANGE Framework project.

[This story was originally published by Honolulu Civil Beat.]