The Hidden Harms of Racial Bullying

This story was produced as part of a larger project led by Deidre McPhillips, a participant in the USC Center for Health Journalism's 2018 Data Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

Aneesah poses for a portrait at the college she is attending in California.

(Kevin German/Luceo for USN&WR)

LOS ANGELES – ANEESAH can still see the flag in her fourth-grade classroom.

"It's how they taught us to be American," she says, "by saying the Pledge of Allegiance."

But Aneesah says she didn't feel very American – or very accepted – in that room. She felt scared.

Aneesah was the only Muslim student at her Southern California school in 2009, and her family was likely one of the only Muslim families in their Rancho Cucamonga neighborhood. With some encouragement from her father, Aneesah was excited to wear a hijab on her first day of school. But the insecurities started to build as soon as she entered the classroom.

Aneesah's teacher hurled several discriminatory comments at her, and eventually ripped the hijab from Aneesah's head. The friends who had wanted to learn more about Aneesah's headscarf earlier that day turned their backs on her, chasing her and calling her names at recess.

"I honestly was terrified," Aneesah says. "I was always a person that would lead people, but this literally broke me. I have trust issues, wondering who will be next to hurt me."

The harassment continued, leading Aneesah's parents to pull her out of public school. Her younger siblings still attend, but the problem of bias-related bullying is still prevalent.

Across California during the 2017-2018 school year, 14% of public high school students said they'd experienced bullying or harassment because of their race, ethnicity or national origin in the past 12 months, a U.S. News analysis of data from the California Healthy Kids Surveyshows. About 6% reported experiencing the same problems because of their actual or perceived immigrant status, and 7% because of their religion.

Aside from in-the-moment suffering, there's evidence this discrimination takes a deeper toll: A further U.S. News analysis of data from the survey, which is managed by the state's education department, shows an apparent link between experiences of bias-related bullying among adolescents and risky health behaviors like smoking and drinking.

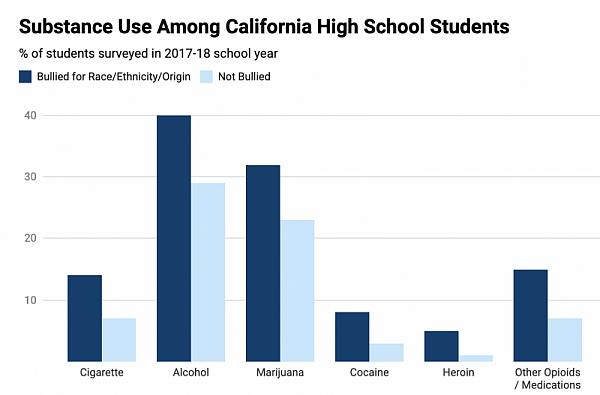

Students in California public high schools who said they'd been bullied because of their race, ethnicity, or national origin were twice as likely to have smoked cigarettes, the analysis shows. Alcohol consumption also was higher – 40% among students who had suffered this bias-related bullying, compared with 29% among those who had not – as were reported usage rates for marijuana, cocaine and heroin, and for prescription opioids, sedatives or tranquilizers.

Participation in the California Healthy Kids Survey is voluntary for school districts and for students, who may choose to answer only certain questions. Through a public records request, U.S. News obtained deidentified, individual survey responses for high school students statewide over school years 2013-2014 through 2017-2018. Responses were grouped by race or ethnicity, year and county for analysis, with the identification of 49 of 58 counties disclosed in response to the request. Five counties were anonymized in the data because they contained only one school district, and four counties did not report survey data.

In the survey, students were asked to indicate how many times in the past 12 months they'd been bullied or harassed on school property because of their race, ethnicity or national origin. Bullying was defined for the students as being "shoved, hit, threatened, called mean names, teased or had other unpleasant physical or verbal things done to you repeatedly or in a severe way."

More than 395,000 students in ninth through 12th grade took the survey for the 2017-2018 school year. Nearly 53,000 said they'd experienced bullying because of their race, ethnicity or national origin in the past 12 months; about 24,000 students left the question blank.

Black students were most likely to experience this type of bias-related bullying, according to the analysis, with more than 1 in 5 reporting that it happened to them. Nearly 70% of those students said it happened more than once, also more than any other racial or ethnic group.

Virginia Huynh, an associate professor in the Department of Child and Adolescent Development at California State University–Northridge, says "prolonged, chronic exposure to discrimination" in adolescence creates greater risk for conditions such as cardiovascular disease and cancer later in life, as its consequences may lead to a biological response and behaviors that can exact a heavy toll on a person's health.

Huynh's research focuses on ethnic minority and immigrant children and adolescents, specifically on how social factors such as discrimination can affect their well-being. A 2016 study by Huynh and others found a link between frequent discrimination and increased levels of cortisol, a stress hormone that biologically prepares the body for fight or flight.

The biological system that controls the body's response to stress is especially sensitive to social evaluative stress – the kind caused by a negative assessment of aspects of an individual's identity, such as race – and it's particularly reactive in teens, Huynh says. While her research doesn't specifically link a rise in cortisol to poor health behaviors, she says the connection makes sense.

"With teens, the prefrontal cortex (for decision-making) is still developing and the reward center is heightened and engaged, which already makes teens more likely to engage in risky behavior," she says. "Combine that with the stress of pervasive, chronic discrimination, and it's logical that risky behaviors would increase."

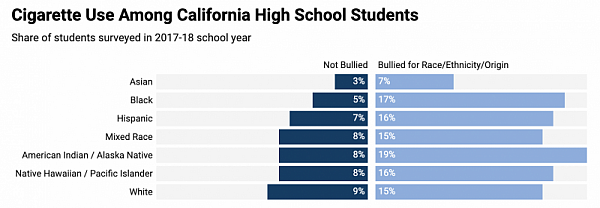

Across California, survey results indicate cigarette use among black high school students overall is uncommon, and is lower only among Asian students. Yet among students bullied over their race, ethnicity or national origin, the U.S. News analysis shows, black students had the highest jump in prevalence of cigarette use: from 5% among non-bullied students to 17% among bullied students. Bullied black and Asian students also saw disproportionate increases in alcohol and marijuana use compared with their non-bullied counterparts.

Korean adolescents experience depression at disproportionate rates and are at relatively high risk for mental health issues in general compared with those of other ethnicities, says Connie Chung Joe, executive director of the Korean American Family Services organization in Los Angeles. She says the current U.S. political climate – with race- and immigration-related tensions – has exacerbated these issues, and anecdotally, she says certain self-harming behaviors have increased in recent years.

"When I look at the youth that we serve through our counseling services here, the biggest issues are depression and anxiety and behaviors that numb some of those emotions or hide them," she says. "There's a lot of self-destructive behavior – bodily self-harm and smoking and drinking that are other forms of self-harm and coping mechanisms."

Measuring the prevalence of bullying – particularly bullying fueled by factors like race, ethnicity or religion – is a difficult task, experts say.

"Each situation is different, and there's a protocol to follow," says Judy Chiasson, who coordinates anti-bullying programs for the Los Angeles Unified School District's Human Relations, Diversity and Equity office. "The legal definition of bullying involves intention, pervasiveness, psychological or physical harm and interference with a student's ability to get an education. Those calls are made by individual site investigators."

Annesah isn't sure her experiences would have been captured in the statistics. She says she brought the situation to the attention of the school principal, who seemed concerned. But while Aneesah was assigned to a counselor to discuss how to manage her emotions, she's not aware of any action taken with the teacher.

Aneesah left the public school system the next school year; an online directory indicates the teacher still works at the same elementary school.

California has one of the most segregated public school systems in the country, says Rebecca Sibilia, founder and CEO of EdBuild, a nonprofit focused on how states fund their schools. And that affects the well-being of students in the system.

According to the U.S. Department of Education's Civil Rights Data Collection – a biennial survey required since 1968 – about 74% of students in the Los Angeles Unified School District were Hispanic in 2015, the most recent year for which data is publicly available through the collection site. About 10% of students were white, while about 8% were black and 6% were Asian.

Yet district schools can look quite different from what overall demographics might suggest. Of the 200 schools within the Los Angeles district, seven had a population that was more than half white in 2015, while a different set of 11 schools had a population that was more than half black.

Similar trends exist elsewhere in the state, data obtained by EdBuild shows, with white students more heavily concentrated in some school districts. Headquartered in Northern California's Trinity County, for example, the Southern Trinity Joint Unified School District – which was 15% nonwhite in 2016 – sits directly above Mendocino County's Round Valley Unified School District – which was 88% nonwhite. Farther south, Fresno County's Sierra Unified School District borders Kings Canyon Joint Unified School District, which were 33% and 91% nonwhite in 2016, respectively.

"The less opportunities that students have to work together, live together, learn together, the less likely they'll be tolerant in the future of different viewpoints and struggles," Sibilia says.

Students in less diverse counties are more likely to experience bias-related bullying. Among the 49 California counties identified in the survey data obtained by U.S. News, nonwhite students were 26% more likely to experience bullying over their race, ethnicity or national origin in the 2017-18 school year if they lived in a county that was more than 75% non-Hispanic white, based on five-year demographic estimates for 2017 from the U.S. Census Bureau's American Community Survey.

Concern about increasing discrimination in society in the wake of President Donald Trump's election appears to have been enough to create stress and lead to poor health behaviors among teens, according to a recent study by researchers at the University of Southern California.

Researchers surveyed more than 2,500 students from 10 different high schools in the Los Angeles area and found that those who reported feeling concerned, worried or stressed about "increasing hostility and discrimination of people because of their race, ethnicity, sexual orientation/identity, immigrant status, religion, or disability status in society" in 2016 were more likely to report more days of substance use or feelings of depression one year later. Increased cigarette smoking was particularly prevalent among Hispanics and African Americans.

"Results like these are unlikely to be a chance finding. They're a representation of what the whole of society is exposed to," says Adam Levanthal, lead author of the study. "We noticed an upward trend in sociopolitical polarization happening after a couple high-profile police shootings, but had no idea it would jump so much after Trump was elected."

Levanthal says the health effects of discrimination among adolescents warrant attention, and at least some lawmakers are on a similar page.

In 2018, California lawmakers approved and then-Gov. Jerry Brown signed a measure aimed at proactively addressing bullying. The new law requires school districts to establish procedures for preventing bullying and make online training from the California Department of Education available to employees who interact with students.

Assemblyman David Chiu, a Democrat who represents the eastern part of San Francisco, sponsored the bill to combat a rise in bullying that he says has been seen in recent years. Nonprofits and civil rights groups backed the bill as well, including California branches of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, Asian Americans Advancing Justice and the Advancement Project, as well as Equality California.

Representatives from the California Medical Association, the California Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and the California Association of School Psychologists also backed the bill.

"There were policies in place that address bullying after the fact, but clearly not enough to combat the increase," Chiu says. "There are some really heartbreaking stories that reflect the national climate."

A 2018 study out of the University of California–Riversidefound that children under 10 years old not only can identify discrimination, but suffer the effects of it. The research also indicates that a strong connection to one's ethnic-racial identity can be an effective buffer to those negative effects.

The group read "Yo Soy Muslim" together, a book by Muslim and Latino poet Mark Gonzalez, and talked about experiences they'd had themselves. Many of the children recounted times they had to explain things about the way they looked, and how they've had to talk to their parents to understand why people were treating them a certain way.

But as the students moved on to a craft project in which they modeled a paper figure after themselves, a sense of pride in their identities was evident.

"You could probably go a little darker," one boy said to another, who nodded in agreement as they held up their hands side-by-side, comparing their skin tones against the paper figures.

"Yeah, that's more like me," the other boy agreed.

[This story was originally published by U.S. News.]