Hidden Peril

This story was originally published in The Inquirer with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

Deon Clark (center) walks home from Lewis C. Cassidy elementary school in Overbrook, one of the 11 schools tested by the Inquirer and Daily News for high asbestos levels.

By Wendy Ruderman, Barbara Laker, and Dylan Purcell

At aging Philadelphia schools, asbestos is a lurking health threat to children and staff. Tests find alarming levels, even after repair work is done.

The beloved teacher in Room 302 at Lewis C. Cassidy elementary school was out on medical leave. Entrusted to a revolving cast of substitute teachers, her fifth graders started to run amok.

By this spring, the 10- and 11-year-olds had turned the narrow closet that stretched the length of Room 302 into an indoor playground. They darted through its doorways, threw play punches, and wrestled on the wood floor.

The children didn’t know it, but they were kicking up something invisible and deadly — asbestos fibers. They likely got them on their hands or in their mouths or even worse — inhaled them, which can take a toxic toll.

At three different spots in this classroom, including the closet, tests by the Inquirer and Daily News have revealed high levels of asbestos fibers in surface dust. As part of an investigation into building conditions at Philadelphia district schools, a Cassidy staffer had taken dust wipe samples in the classroom and an accredited lab analyzed them for the newspapers.

A patch of floor in the closet — where students hang backpacks and store lunches — came back at more than 4 million asbestos fibers per square centimeter. That result is 50 times higher than the highest result for settled asbestos dust found indoors in apartments near ground zero after the 9/11 terror attacks.

When a reporter called teacher Sharon Bryant on May 2 with lab results for her Room 302, she broke down.

“My kids are breathing it in,” Bryant said, crying. “You’ve got to get my babies out of there.”

The test results were also shared that day with officials at the School District of Philadelphia. Pressed for a reply, a district spokesman on May 9 said that in the past day or two “we have looked into the environmental conditions in this classroom and will address any issues, if needed.”

Asbestos fibers, which can be found in nearly all of the pre-1980 district schools, are hazardous when airborne. Experts, however, say 100,000 fibers per square centimeter or higher in surface dust are cause for alarm. Asbestos fibers can be easily stirred up and linger in the air for hours or days in bustling school hallways and gymnasiums, or in classrooms where small children sit on the floor for story time.

Bryant, a teacher for the last 25 years, has reason to worry about her students — and herself. Elementary and middle-school teachers are the third-highest profession, behind construction workers and plumbers, to succumb to the devastating effects of asbestos, according to 2012 data from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

“I’m worried about my lungs, and my lungs are almost 60. My babies’ lungs — they are just developing,” said Bryant, 59, her words catching in her throat. “How can this be happening in 2018? Are we running an experiment?”

As part of its “Toxic City” series, the Inquirer and Daily News investigated how environmental hazards in district buildings all across Philadelphia put children at risk and deprive them of healthy spaces to learn and thrive.

During the last eight months, reporters examined five years of internal maintenance logs and building records, interviewed more than 120 teachers, students, nurses, parents, and experts, and enlisted school staffers to help test for four health hazards: mold spores, lead in water, lead dust from chipping and peeling paint, and asbestos fibers in settled dust.

Staffers at 19 of the district’s most rundown elementary schools agreed to conduct tests. Reporters provided them with lab-issued equipment and written instructions on how to follow scientific guidelines. Of the 19, staffers at 11 schools tested for asbestos fibers on surfaces.

A sample of settled dust taken in January from the floor around this hallway pipe near a sixth-grade classroom at Olney Elementary tested at 8.5 million asbestos fibers. The asbestos pipe is partially encased in a metal jacket.

The investigation found alarmingly high amounts of asbestos fibers on floors in gyms, cafeterias, hallways, classrooms, and auditoriums. Test results in six of the 11 schools, including Lewis C. Cassidy Academics Plus, came back above 100,000 asbestos fibers per square centimeter. The highest test result — 8.5 million asbestos fibers — came from a floor near an insulated pipe in a hallway just outside a sixth-grade classroom at Olney Elementary School.

District officials have criticized the newspapers’ testing. They questioned the collection methods and argued that air monitoring for asbestos — not surface wipes — is far more accurate and is the only testing method required by law.

“It does concern us to see tests done in schools where we don’t know about how they’re being performed. Is the person qualified and taking the sample properly?” Francine Locke, the district’s environmental director, said in a March interview.

But several independent asbestos experts validated the newspapers’ approach, calling surface tests “a very powerful investigative tool.” In fact, the Environmental Protection Agency used that method to help qualify Libby, Mont., as a Superfund site for asbestos cleanup.

The Inquirer and Daily News investigation also found that damaged asbestos has gone unrepaired in schools for up to two years, inspection records show. That was true even when inspectors flagged the repairs as “high priority.”

Even after asbestos repairs were made and officials said students could return, large amounts of fibers were left behind on surfaces in some cases, according to the newspapers’ testing.

“We shouldn’t have any asbestos in any dust anywhere,” said Christine Oliver, a former Harvard Medical School professor and author of a 1991 study about the health impacts of asbestos on custodial staff at Boston public schools.

“Settled dust is settled one minute and then the next minute, it’s entrained and it’s in the air and in your breathing zone.”

‘WE GROSSLY UNDERESTIMATE’

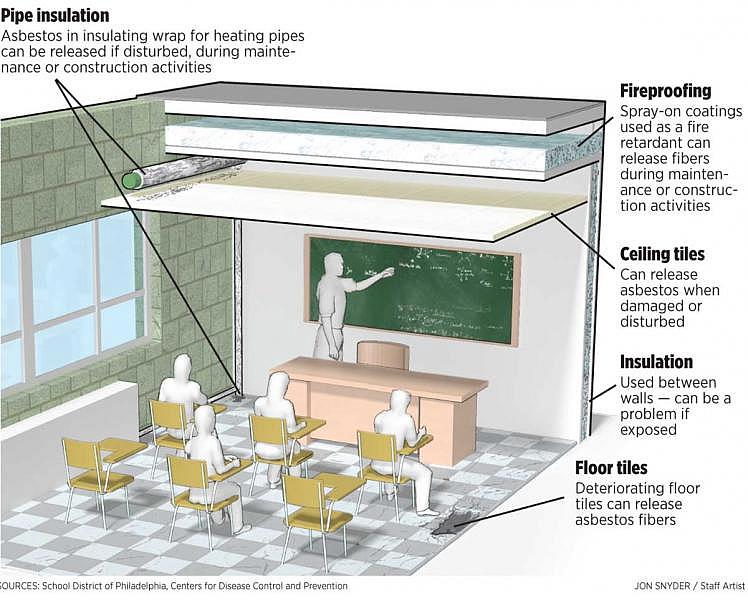

Asbestos, once dubbed a “magic mineral” for its durability and heat resistance, can be found nationwide in schools built before 1980. It can be found wrapped around steam pipes as insulation, sprayed on walls and ceilings as soundproofing in auditoriums, and found inside floor and ceiling tiles. Even the adhesive that holds floor tiles in place may contain asbestos.

But perhaps nowhere is the reckless legacy of asbestos more acute than in Philadelphia schools, with an average age of 70 years, and a dozen so decrepit they should be knocked down and replaced. Roughly 11 million square feet of asbestos remain in district buildings — enough to cover the Pennsylvania Convention Center more than 11 times over, according to the newspapers’ analysis of district records.

Reporters were able to collect dust samples to test for asbestos on 84 surfaces inside 11 Philadelphia district schools. Nine of the schools had elevated asbestos fiber counts in student-accessible areas. Half of the samples were above 5,000 fibers per square centimeter, the level the EPA set to qualify for federal cleanup of apartments near Ground Zero. Asbestos abatement professionals typically use air monitoring to detect the number of fibers. Dust-wipe sampling is an investigative tool to indicate potential airborne hazards.

Asbestos in tiles and insulation isn’t dangerous if these products are kept in good condition. But after years of wear and tear, the fibers can break off and be released into the air. The microscopic fibers are so lightweight, they can float for hours.

Inhaled over time, the fibers can cause asbestosis, a debilitating lung disease, and mesothelioma, a rare aggressive cancer that develops in the lining of the lungs, abdomen, or heart. Asbestos has also been linked to cancers of the esophagus, larynx, stomach, kidney, colon, rectum, and ovaries.

“We grossly underestimate the impact of asbestos as a cause of disease,” said physician Arthur Frank, an environmental and occupational-health professor at Drexel University’s Dornsife School of Public Health.

The fibers are like spears, needle-sharp. But they are too small to be felt when they pierce organs and body tissues. “The asbestos fibers can go everywhere in the body,” Frank said.

Whether someone develops a disease largely depends on the amount and duration of exposure.

People who develop asbestos-related diseases show no sign of illness because it can take 10 to 50 years or longer for symptoms to appear. The EPA has concluded that the only safe level of exposure to asbestos is zero.

In the 1980s, federal lawmakers recognized that asbestos in schools was such a massive problem that they enacted a law in 1986 designed to protect students from exposure: the Asbestos Hazard Emergency Response Act (AHERA).

Under the Reagan-era law, the school district must keep records of all asbestos, noting its location and condition in each building. The district is required to do a comprehensive building inspection every three years and a visual walk-through every six months. The district removes or repairs asbestos, on average, more than 200 times a year, city records show. According to a budget for fiscal year 2017-18, the district plans to spend more than $5 million on major asbestos jobs.

When the Philadelphia district did its last full inspection in the 2015-16 school year, more than 80 percent of the schools had damaged asbestos. In all, gouged, cracked, or loose asbestos was found in 2,252 locations, including many frequented by children, according to the newspapers’ analysis of district records.

In more than one quarter, or 639 locations, the district’s environmental inspectors were so concerned that they marked the damage spots as “high priority” and “newly friable” because of the potential health risks. (“Friable” refers to asbestos that “when dry, may be crumbled, pulverized, or reduced to powder by hand pressure,” according to federal regulations.)

Damaged asbestos must be repaired or removed “in a timely manner,” although “timely” is not defined in the federal law.

At the A.S. Jenks school in South Philadelphia, a test by the newspapers found the asbestos level on the gym floor far exceeding the EPA minimum to qualify for a federally funded cleanup.

The district’s interpretation of timely may be seen in the case of the gymnasium at A.S. Jenks Elementary in South Philadelphia.

For the last five years, the district has documented damaged asbestos pipe insulation, including a 2015 report of a “gouge, 10 inches high, near ceiling heater fan unit.” Inspectors had flagged the gym as “high” for “air movement” and “activity,” records show, conditions that can send fibers airborne.

In December, the newspapers’ test of an area on the gym floor at Jenks detected 55,500 asbestos fibers per square centimeter. That number is 11 times higher than the amount the EPA established as the minimum asbestos level to qualify for a federally funded cleanup in the wake of the World Trade Center collapse.

The district, in an April 9 email to reporters, wrote that the damaged pipe insulation in the Jenks gym is “not considered a friable hazard,” and therefore doesn’t require an immediate response under the law. Officials said the damaged asbestos, first noted years ago, will be repaired this summer.

DAMAGED ASBESTOS BEDEVILS MANY SCHOOLS

In Philadelphia district schools built before 1980, asbestos can be found wrapped around pipes as insulation, sprayed on ceilings as sound-proofing, and in floor tiles. If undamaged these products are considered safe. But damaged or “friable” asbestos can release invisible fibers linked to devastating lung diseases. Below: damaged asbestos locations in district-run schools based on inspections from the 2015-16 school year and from more recent reports.

‘DUST EVERYWHERE’

Lisa Clark, with son Deon, worries about asbestos’ long-term effects on students. “Who’s to say that they won’t have a higher rate of cancer as adults?”

After Sharon Bryant’s son, her only child, died in a car accident a decade ago at age 26, she found herself more protective of her students, calling them her “babies.”

Bryant went out on medical leave in December after she hurt her back and neck. That’s when her students at Cassidy in Overbrook admit they started to act up.

“When Miss Bryant is gone, there is a lot of play in the closet,” said Jihad Ellis, 11, adding that “there’s dust everywhere inside the closet.”

“When the substitute is there, they get a little out of hand and they play-fight,” said Deon Clark, 11. “Kids roll around on the floor in the closet.”

When Deon’s mom, Lisa Clark, was told about the high amounts of asbestos fibers in her son’s classroom — his homeroom for the last two years — she was horrified.

“I am just so scared now. Very scared. Because if asbestos is everywhere, what is going to happen in the long run?” Clark asked. “These are children. They’re still developing. Who’s to say that they won’t have a higher rate of cancer as adults?”

Jihad’s stepdad, Maurice Stewart, said he was at a loss as to what to do.

“Do you pull your kid out of school and then he gets no learning at all?” Stewart asked. “What do you do? Do you make him go to the school with a mask on? Like, what do you do?”

‘A TEAM’ ON A MISSION

Olney Elementary, where the newspapers’ testing found the highest asbestos level — 8.5 million fibers — in a hallway outside a sixth-grade classroom.

Last September, the district dispatched its “A Team” — respirator masks, disposable Tyvek suits, and other protective gear — to Olney Elementary School on North Water Street. The A Team is the nickname of a group of highly trained staffers who are state-certified to remove and repair asbestos.

Their mission: Remove damaged pipe insulation in a women’s staff restroom and abate deteriorating asbestos in five other locations in a school built in 1900.

Twenty months earlier, building inspectors had noted a steam or water leak in that restroom had damaged asbestos around a pipe. They termed it “newly friable” — meaning fibers could be easily released into the air or settle on the floor. They could be stirred up or inhaled. The repair job was termed “high priority,” but not an “imminent hazard,” records show.

Under city and federal asbestos regulations, A Team workers had to first seal off the repair areas with plastic sheeting, clean inside the barriers using wet mopping and vacuums with HEPA filters.

Working alongside them was an independent, state-accredited environmental firm, Synertech. It would oversee the A Team’s work and, at its conclusion, analyze air for fibers, as required by law.

That law also called for the pipe-abatement job in the women’s restroom to be concluded with “aggressive” air sampling: stirring up the air inside the tented area with a leaf blower and a fan, and then air testing with a filtered vacuum pump.

Aggressive air sampling wasn’t done, according to a review of Synertech records provided to the district. On a September night, Synertech deemed the air safe for students to return and A Team workers packed up and left. (Synertech’s project manager did not return phone calls seeking comment.)

Three months later, at the reporters’ request, an Olney staffer collected surface dust from five areas in the school, including from the floor of the recently repaired women’s restroom and from the floor near a pipe in a hallway nearby. Reporters asked for the samples as part of an effort to determine the quality of asbestos abatement work at the district’s most rundown schools.

On Jan. 25, test results came back elevated: The women’s restroom had 46,300 asbestos fibers per square centimeter in settled dust. The hallway had an astonishing measure — 8.5 million.

A reporter alerted the school district about the results within hours.

Locke, the district’s environmental director, consulted with Jerry Roseman, the environmental science director for the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers. “He was very adamant about going in and taking a look at that and doing something in response,” Locke said in an interview. “So we did.”

Within a week, the A Team was back at Olney — after school hours — to address the 8.5 million-fiber hot spot.

CRUDE DETECTION METHOD

How could the district’s highly trained asbestos team leave a potentially dangerous level of asbestos fibers behind?

One reason may be that abatement crews did not follow the rigorous cleaning guidelines set by local and federal law.

Another reason lies in the outmoded testing method that the Philadelphia district and others across the country rely on to check air for asbestos after minor repairs are concluded.

Under the 1986 federal law, school districts can use Phase Contrast Microscopy (PCM) testing, which can be done on site usingaportable microscope. But this method is too crude to detect the thinnest and shortest asbestos fibers, a kind that can cause mesothelioma. Of the larger fibers it can detect, this method counts them as asbestos, even though they may beharmlessmaterials.

Science has evolved. The law has not.

For large asbestos removals, the Philadelphia district is required to use a far more sophisticated method to test the air once the work is done. Called Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM), this high-magnification method has the ability to detect the tiniest fibers. Unlike PCM, this method takes more time, costs more, and must be done in a lab. A six-hour-rush result for TEM costs $76 compared with $14 for a PCM version.

The newspapers used TEM for all of their asbestos surface tests. The work was done by International Asbestos Testing Laboratories, or iATL, a nationally accredited lab in Mount Laurel, Burlington County. The majority of asbestos fibers found by the newspapers’ testing were chrysotile, so microscopic that PCM would not identify them.

Experts agree that relying on PCM air testing to clear small abatement jobs can create a false sense of security.

“Air sampling has proven in the past to provide false negative results, even with asbestos fibers numbering in the hundreds of thousands, or even in the millions, on a surface,” said Robert J. DeMalo, an executive at EMSL Analytical, an environmental testing lab. He recommends school districts do periodic surface testing for asbestos “to protect our children — they’re a sensitive population.”

A RELAXED OPTION

The Philadelphia Department of Public Health has some of the nation’s most stringent rules when it comes to asbestos removal.

Yet the school district can skirt local regulations when it comes to asbestos tile.

The health department considers all asbestos tile removal to be hazardous, a process that requires serious protections. But it allows a waiver if the tiles are undamaged and can be removed intact.

The district routinely takes advantage of this more relaxed option.

School officials argue that a scratched, cracked, or chipped tile is not damaged. Tiles only pose a health risk when they crumble under hand pressure or break into tiny pieces, the district’s Locke said.

ASBESTOS IN OUR SCHOOLS

Olney Elementary, where the newspapers’ testing found the highest asbestos level — 8.5 million fibers — in a hallway outside a sixth-grade classroom.

In schools built before 1980, asbestos is most commonly found in insulation and building materials. It was also widely used in floor and ceiling tile, acoustical and decorative insulation, pipe and boiler insulation, and spray-applied fireproofing.

When removing tile, school officials routinely ask the health department for “an alternative method request” that, if approved, allows them to do the work with fewer safeguards.

Given the district has its own trained and licensed asbestos contractors, the health department takes it at its word that the tiles are intact and grants the requests.

There is damaged floor tile all over district schools:

In the 2015-16 school year, inspectors noted 960 locations with damaged asbestos floor tile, totaling roughly 12,300 square feet. The damage included 44 square feet in Cassidy’s gym/cafeteria, 399 square feet inside H.A. Brown Elementary in Kensington, and 109 square feet inside J. Hampton Moore Elementary in the city’s Northeast section.

Hampton Moore was one of the 11 schools where staffers agreed to test for asbestos fibers. In October, a staffer took a dust wipe sample from a cracked, delaminated tile in a second-floor hallway. The lab result came back at 1.9 million fibers per square centimeter.

Two months later, the district filed “an alternative method request” with the health department, describing the cracked tile as “non-friable.” The district’s A Team removed 32 of the damaged tiles, roughly 15 square feet.

With the waiver in hand, district workers didn’t have to enclose the area. Nor did they have to close out the job with “aggressive” air testing. They didn’t replace the tiles or remove asbestos-based mastic that glued the tiles to the floor.

Three days after the A Team left, a Moore staffer took four dust wipe samples from the area. All came back extremely high. A patch of missing tile tested at almost 2.6 million fibers.

On April 17, a reporter told district officials that, according to health department rules, the Hampton Moore job shouldn’t have qualified for a waiver: Its tiles were damaged, not replaced, and the mastic was still exposed. Children had walked over the area for months.

Two days later, a district worker arrived at Moore to lay down new tiles.

RESTLESS AND CLAMMY

Sharon Bryant, a teacher at the Cassidy school, leaves a medical office after her ear, nose, and throat doctor told her she needs additional testing due to asbestos exposure.

Inside Room 302 at Cassidy, asbestos wasn’t found only in settled dust on the floor.

One sample from an area on top of the air-conditioning unit in the classroom tested at a hazardous level, 370,000 asbestos fibers, lab results show.

The first week of May brought a steady stream of humid, summerlike conditions.

On Wednesday, May 2, a reporter made the district aware of the lab results, especially the high asbestos residue on top of the air conditioner, fearing that if the unit were turned on, it could blow the fibers all over the classroom.

There was no reply and no signs a cleanup was performed.

But the chief of external relations, Kevin Geary, e-mailed some talking points the next day to the district’s principals.“If asked about the Inquirer’s test results, please note that we have made clear to the newspaper that we do not agree with the reporters’ methods to obtain data and to conduct their own tests in ways that do not align with industry standards, and city/state/federal regulations.”

Two days later, by 11 a.m., temperatures had crept into the 80s. Room 302 was beginning to get hot and sticky.

The fifth graders grew restless and clammy. There was about an hour left before early dismissal.

That’s when Deon Clark said one of his classmates got up and walked over to the air-conditioning unit at the back of the classroom.

And flipped the switch.