How small rebellions by Florida delinquents snowball into bigger beatings by staff

This article and others in this series were produced as part of a project for the University of Southern California Center for Health Journalism’s National Fellowship, in conjunction with the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

Other stories in the series include:

Powerful lawmaker calls for juvenile justice review in wake of Herald series

An officer used a broom to beat juveniles into submission. They called it ‘Broomie.’

Criminal record? Horrible work history? Florida juvenile justice would still hire you

At this juvenile justice program, staffers set up fights — and then bet on them

Dark secrets of Florida juvenile justice: ‘honey-bun hits,’ illicit sex, cover-ups

FIGHTCLUB: A Miami Herald investigation into Florida’s juvenile justice system

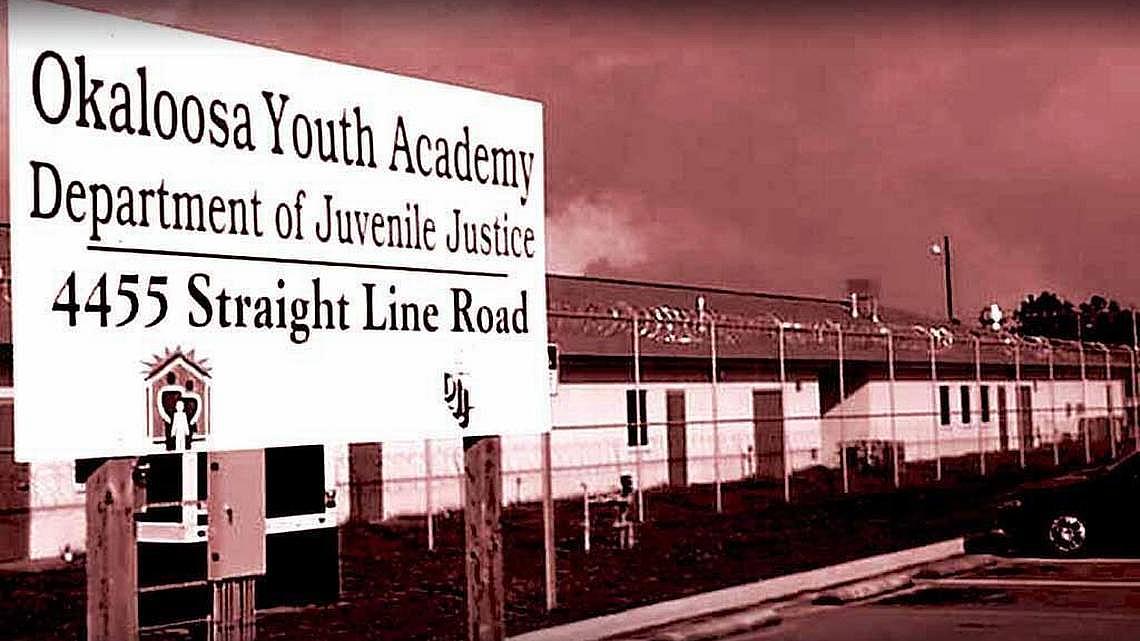

Okaloosa Youth Academy-Gulf Coast Youth Services

By Carol Marbin Miller and Audra D.S. Burch

First he lost his freedom. Then his privileges. Then his kidney.

It started with a tantrum at a youth program on Straight Line Road over what the Tampa boy considered unfair punishment for a fight he didn’t start. A program supervisor hurled the teen to the dayroom floor, crashing him into a metal table along the way. It ended with the boy tethered to a ventilator.

A youth is tossed violently into a metal table at an Okaloosa County residential program. He sustained an injury that required removal of a kidney. As he writhed, a staffer asked if he was now calm. -Florida Department of Juvenile Justice

Are you calm now? the supervisor asked as the boy writhed in pain on the floor.

The Department of Juvenile Justice declared the worker’s takedown at Okaloosa Youth Academy a case of excessive force. The boy called it a deliberate act of violence that consigned him to a life without a right kidney. “By the look on his face,” said a youth who witnessed the takedown, the worker “appeared to be angry.”

State files obtained by the Miami Herald are filled with stories of juveniles needlessly — sometimes brutally — restrained, in numbers that some experts say far exceed what is necessary.

It often started with acts of adolescent rebellion: They threw wads of crumpled paper. They mouthed off to their jailers. They cursed and spat at staff. They refused to go to bed. Or they refused to get out of bed.

For their juvenile contempt and disrespect, they were met with harsh discipline: takedowns and body slams.

Retaliation reportedly has included a head plunged into a toilet and assaults with broomsticks, a flashlight, a radio and whatever other hardware was handy.

Ankles to eye sockets

Records examined by the Herald show youths held in Florida lockups and residential programs have sustained every conceivable injury: broken arms, shoulders, wrist, necks, legs, ankles, noses and eye sockets; concussions and other traumatic brain injuries; sprains, bruises, cuts, gashes and black eyes. One suffered a lacerated lung. Another allegedly was diagnosed with potentially deadly cellulitis after a staffer bit him, resulting in multiple medical and psychiatric hospitalizations.

Some of the most dangerous kinds of takedowns — headlocks, chokings and full-body restraints — also have become among the most common, records show.

A youth at Duval Academy who shows no aggression is taken down violently by a large member of the staff. -Florida Department of Juvenile Justice

Bad judgment has bordered on the bizarre: One worker who felt insulted summoned her husband, who went on a stabbing spree, gashing both a staffer and the offending youth — twice. Another was terminated after he fired a nail gun at detained teens. Still another flung a plastic lawn chair into the face of an eighth-grader with special needs — who was in a wheelchair — and then punched the boy repeatedly, after a tiff over television time.

“There’s an acceptance of a culture of violence,” said Paul DeMuro, who has worked as a juvenile justice administrator and consultant for 41 years, including a stint as a federal court-appointed watchdog in Florida. “Staff frequently depends on restraints, takedowns and chokings as a response to misbehavior. But how do you eradicate that kind of misbehavior if that’s the very intervention you are relying on? That’s nuts.”

DeMuro added: “The core issue is you should not use force to teach people not to use force.”

DJJ Secretary Christina K. Daly said that while her agency oversees a correctional system, “I think we have made tremendous strides in softening and refocusing how we look at our children.”

Daly said DJJ was “in the process of revamping” the agency’s restraint policies, encouraging workers to use physical force only as a last resort. “You can get the same outcome by conversing with them and having mutual respect for them. There are some staff who get that, and there are some staff that don’t,” Daly said. “We slowly try to weed those people out.” DJJ later acknowledged that negotiations over a contract to develop a new crisis intervention curriculum fell apart, so the agency hired someone to refine it.

“We don’t want staff putting hands on kids,” Daly said.

Data provided to the Herald show how frequently staffers do just that. Systemwide, a youth was restrained, on average, three and a half times every day during the 2016 budget year. Much of that physical force is unwarranted. During the past decade, youths reported unnecessary, excessive or “improper” force 4,092 times — on average, more than once every day. Of those complaints, 1,014 were substantiated, DJJ records indicate.

While some programs goes months without reporting a restraint, others post numbers that far exceed the state’s threshold. In the 2016 budget year, for example, the restraint rate for the Martin Girls Academy was more than seven times the state average.

Vincent Schiraldi-LinkedIn

“These numbers are astronomical,” said Vincent Schiraldi, a senior research fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School who was director of juvenile corrections in Washington, D.C., from 2005 until 2010, and then commissioner of New York City’s youth probation department until 2014. “They should be the cause of concern for anyone who cares about a well-functioning department — and the welfare of young people.”

There are reasons to believe that the numbers don’t reflect reality — and that the magnitude of the problem is greater.

Over the past decade, juvenile justice administrators investigated 971 claims that a youth worker did not report the suspected wrongdoing of a colleague, substantiating 644 of them, according to a database the Herald obtained from the state. DJJ investigated an additional 484 reports that workers falsified records, sustaining 268 of those.

What’s unknowable is how many cover-ups were not detected, never resulting in allegations of “failure to report.”

The prevalence of staffers “stashing” incidents of misconduct — as shown in the existing data — suggests that workers have great confidence they’ll never be punished, which “can contribute to an atmosphere of lawlessness within these facilities,” Schiraldi said.

“Think of how frightening it is to be a kid and, no matter what a staff member does, he can’t be held accountable for it,” he added. “It puts these kids at the mercy of staff.”

A parallel reporting system separate from DJJ’s is run by the Department of Children & Families. But the statewide DCF child abuse hotline may similarly underestimate the maltreatment of detainees. By law, youths have a right to call the hotline, but that doesn’t mean their claims will be investigated. DCF has no jurisdiction over detainees 18 or older, as some in the system are.

And hotline operators can decline to accept reports for a variety of reasons, sometimes offering little or no explanation.

Wrong number — maybe

The Herald’s examination of thousands of documents turned up cases where detainees allege they were denied access to the hotline phone or bribed with snacks to refrain from reporting. At the privately managed Fort Myers Youth Academy, staffers said they were forbidden to call the DCF hotline without explicit permission of top management.

Reports from DJJ’s inspector general detail several examples of workers cajoling detainees to relinquish their right to report mistreatment.

And then there was this: Late last year, a boy at the Spring Lake Youth Academy in Arcadia claimed that his abuse report was made to a bogus hotline.

“I’m not scared of you,” the youth said after a supervisor tossed his sneakers into a trash can. Details of the encounter that followed read a lot like child abuse: The youth told investigators the supervisor punched him in the face, pushed him to the floor repeatedly and then “kneed” him in the left ear, making him bleed. Four other detainees said they saw the supervisor slug the boy.

When the detainee insisted on reporting the incident, the supervisor threatened to charge him with escape. The boy persisted, and the supervisor “dialed the phone and handed it to him,” a report said. The kid had serious doubts that the hotline operator was legit.

The “operator” failed to ask where he was detained or who had hit him.

When the alleged beating was reported — after the youth told the program’s top administrator four days later — it marked the 12th complaint against that particular supervisor, including four prior allegations of excessive or unnecessary force. None of those prior cases was substantiated. This one was. DJJ didn’t officially determine whether the “hotline” call was a fake, although a report noted that the institution’s official phone “revealed no call to the Abuse Registry was made on that date.”

The worker’s punishment: He was reprimanded for improper conduct and violating policies or rules, coached for his failure to report the restraint, and trained for the excessive force, the report said.

In Loyalty Cottage, a restraint that wasn’t

Restraints by staff at juvenile justice facilities are known as PARs, which stands for Protective Action Response. Youth care workers and officers are trained to deploy force only when other options, such as “verbal de-escalation,” fail, and to limit the injuries to detainees. Every PAR must be documented and reported. One way around that — and the Herald found an example of this in the files — is to claim that a restraint didn’t follow proper protocols, making it technically not a restraint, and therefore not reportable.

At the Residential Alternative for the Mentally Challenged, a program for boys in Madison, a 16-year-old said an officer “banged” his head against a wall repeatedly in the Loyalty Cottage in April 2014. He had annoyed the staffer by cursing and “rapping” — and later poked his finger near the worker’s face.

The program administrator later stated that a use-of-force report to the state wasn’t warranted because the shoving incident didn’t amount to “PAR technique.” DJJ disagreed. The administrator was counseled for failure to report, and the worker was fired.

After obtaining DJJ and DCF’s databases covering 10 years, the Miami Herald ordered hundreds of case files. Among the patterns that emerged:

▪ Examples of officers and youth care workers steering detainees into cells and dorm rooms, bathrooms and corridors just beyond the view of surveillance cameras for improper takedowns or attacks.

▪ Chokings, headlocks and “clotheslinings” — stiff-armed takedowns — all of which are seen as especially dangerous ways to subdue a belligerent youth.

▪ A reluctance of investigators to give credence to detainee complaints. DCF verified slightly more than 5 percent of abuse claims from detained youths, but around 17 percent to 20 percent of all abuse or neglect reports received from schools, homes and everywhere else.

▪ Officers escalating matters by roughing up detainees who offered only passive resistance and did not present a danger.

Curbing such practices takes time, said DJJ’s Daly. “Our challenge is that it is a massive system and culture change does not happen overnight,” she said.

True culture change 'takes time'

DJJ Secretary Christina K. Daly talks about weeding out staffers who are not on board with the department's reform efforts. -Emily Michot

Troubling temperament

In Melbourne, a youth worker at the Space Coast Marine Institute watched as a colleague “clotheslined” and took down “an unsuspecting youth.” The colleague, who happened to be the institute’s restraint instructor, “had his arm around the throat of [the teen] and was choking him,” the worker said. “He could hear the youth telling staff ... to ‘let go of my neck, let go of my neck. I can’t breathe.’ ”

None of that came out until 10 days later.

The result: an excessive force complaint and eventual termination of the aggressor.

Also dismissed: the worker who didn’t report it right away.

His explanation: “He feared if he reported the wrongdoing ... to administration, the other staff would retaliate, embarrass him in front of the youths and other staff, and work to get him fired,” according to an administrative review.

Restraints in which a youth stopped breathing have been implicated in the deaths of at least two youths in the custody of DJJ. Twelve-year-old Michael Wiltsie was asphyxiated on Feb. 4, 2000, when his counselor at Eckerd’s Camp E-Kel-Etu straddled Michael — even as the boy wailed that he couldn’t breathe. Michael weighed 66 pounds; his counselor, 300.

Almost six years later, 14-year-old Martin Lee Anderson stopped breathing as officers at a military-style boot camp in Panama City used force to coerce him to run a track. Martin, detained for joyriding in his grandmother’s Jeep, insisted he couldn’t catch his breath and wilted.

The mauling — which went on for half an hour — was captured on video, and its release following a Herald public records lawsuit sparked an outcry. An autopsy by a Tampa medical examiner appointed by a special prosecutor concluded that Martin suffocated when officers shoved ammonia capsules up his nose.

The restraint that shocked Florida

Martin Lee Anderson, 14, is fatally manhandled at Bay County Boot Camp as a nurse watches. After he was unable to run a track, he endured punches, knee jabs and “pressure points,” and died from having ammonia capsules jammed up his nose. -Florida Department of Juvenile Justice

A Herald review found close to 30 cases in which DJJ substantiated an unnecessary or excessive force case that included allegations of a youth being choked, placed in a headlock or choke-hold, or grabbed by the throat. Since 2008, DCF investigated 689 allegations of “asphyxiation,” or intentional choking, verifying 23 of them. DCF found some evidence to support 80 other asphyxiation allegations, but not enough to verify them.

Agency rules explicitly state that officers and youth care workers may not restrain detainees who are not a threat to people or property, such as when a youth ignores an order to sit down.

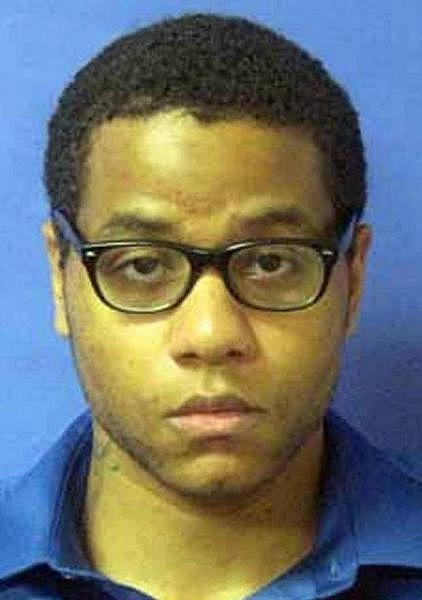

At the Marion Youth Academy, several boys noticed something troubling about youth counselor Curtis Thornton’s temperament — even before he “snapped” and sent a teen to the hospital. “Thornton had anger issues and he gets mad very easy,” recounted one youth’s statement to DJJ.

'I proceeded to redirect the youth to the floor'

That was Curtis Thornton's description of this beatdown at Marion Youth Academy. Witnesses said the staffer, reputed to have a volatile temper, snapped. The 16-year-old victim had to be hospitalized. -Florida Department of Juvenile Justice

At 2:40 p.m. on Feb. 12, 2015, Thornton and a 16-year-old were laughing and tossing crumpled paper at each other during science class, witnesses said. Thornton grew tired of the horseplay. When the youth threw one last paper wad, Thornton “became enraged,” a DJJ report said.

Sheriff’s detectives described what happened next — which was captured on video: “He suddenly and without warning turned around and struck the victim full force, knocking him backward out of his chair, with what appeared to be a punch to the head. As the victim laid on the ground, [Thornton] straddled the victim and began striking him repeatedly until other juveniles separated the two.”

For his first strike, Thornton wielded a portable radio, which broke into pieces. The video recorded “a minimum” of seven additional blows, a report said.

Curtis Thornton Florida-Department of Corrections

“Stop, what the ‘F’ are you doing, he’s a youth!” one of the boys said, according to his written police statement. “I don’t give a ‘F,’ ” the boy said Thornton replied.

The 16-year-old fainted as blood poured from the left side of his forehead. Doctors stapled the “gash” to close it, a DJJ report said. The boy also had smaller cuts to his elbow, cheek and hand, police said.

Thornton, 26, said the youth had wanted to fight all that day, and had goaded him repeatedly with paper wads. “I proceeded to stand and redirect youth to the floor, securing him there until additional staff arrived,” he wrote.

Jurors didn’t concur. After deliberating for two hours, they convicted him of child abuse.

It had been Thornton’s second tour through the criminal justice system — though with a less happy ending. In July 2013, an Ocala police officer arrested Thornton on charges of domestic battery after his girlfriend said he punched her in the chest, knocking her into a wall and cutting her elbow. The charges were dropped a month later when the alleged victim declined to cooperate with prosecutors, court records show. Thornton could not be reached by the Herald.

‘PAR’d him on his head’

Beyond being fired, youth care workers seldom are held to account for “PARs” that are more battery than “Protective Action Response.”

When a teenager refused to eat his breakfast on the concrete slab of an outdoor porch in January 2015, witnesses said a worker “PAR’d him on his head.” Less technical accounts held that the worker threw the boy to the ground on his skull.

Descriptions of the events leading up to the takedown at Big Cypress Youth Environmental Services varied, and the restraint itself occurred beyond camera range. The detainee said that the worker, annoyed when he didn’t follow orders, put his breakfast tray on the concrete and ordered him to eat it there. The boy refused, saying he “was not going to eat his food on the ground like a dog.”

Though the staffer said his restraint complied with state rules, two youth witnesses told an investigator that the officer lifted the youth off the floor and “slammed” him into the concrete, headfirst.

The victim said he laughed at the officer after the first slam, but the laughter stopped when the the man “slammed him two additional times,” an inspector general report said.

The detainee collapsed, “unresponsive,” and was carried to an ambulance by stretcher. At a nearby hospital, he was diagnosed with traumatic brain injury.

The inspector general report said it “appears that the youth’s injuries would be consistent with the youth being slammed to the ground, or brought down in a very aggressive manner, and this is clearly not an approved technique.”

Then, without further explanation, it concluded that “there were no reasonable grounds to believe there has been a violation of criminal law.”

The body slam was never reported to police.

[This story was originally published by the Miami Herald.]