Introducing 'Aftershocks,' a series about surviving gun violence in Chicago

This story is part of a larger project led by Lakeidra Chavis, a 2020 Data Fellow, who is reporting on how the pandemic has affected shooting survivors in Chicago.

Her other stories include:

More Than 30,000 People Shot In Chicago In 10 Years. Here’s What Survivors Say Is Needed.

Chicago Shooting Survivors Face Recovery With Few Resources

How We Reported on Illinois’s Victim Compensation Program

How to Report on Victims Compensation in Your State

Part 1: In Chicago’s Roseland Neighborhood, a Mix of Grief and Perseverance

Part 2: Illinois Has a Program to Compensate Victims of Violent Crimes. Few Applicants Receive Funds.

The Trace

Gun violence weighs on Chicago’s conscience.

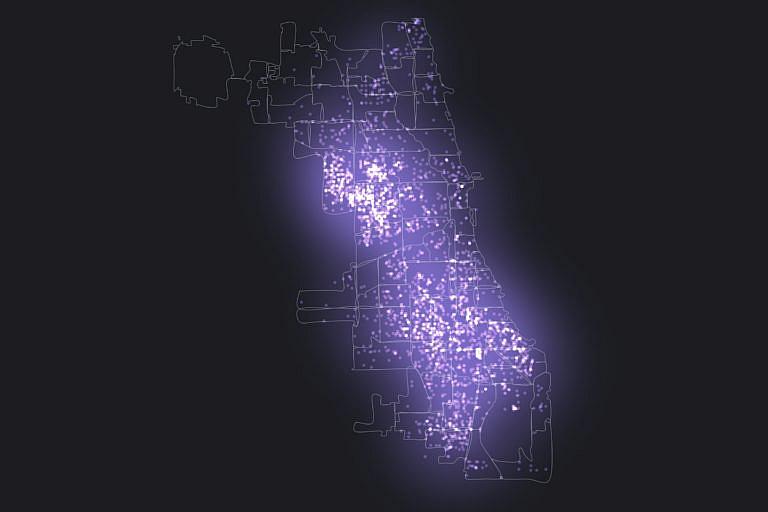

On any given day, there can be as many as a dozen shootings. They happen outside Citgo gas stations on Washington Boulevard, or blocks away from the schools near 51st street. People are shot in cars and on the stoops of their brick-laced three-flats.

But after gun violence, life is more common than death. Of the more than 30,000 people who have been shot in the city in the past decade, 5 in 6 survived. Most victims are Black and Latinx. More than half are barely on the cusp of adulthood.

The trauma of surviving can last a lifetime, and is never exclusive to a single person's mental and physical recovery. Each incident has a ripple effect that extends to dozens: From the first responders, to witnesses, fathers, mothers, sisters, and brothers — not to mention the nearby businesses.

Together, they form a loose community, left to cope with PTSD, chronic pain, and grief.

But even with that shared struggle, they’re often on their own. The Trace spent months analyzing police and homicide data, and speaking with residents directly affected by gun violence. We found that a state program designed to help victims and their families, for the most part, was failing to do so. Illinois’ Crime Victim Compensation Program, a decades-old effort designed to reimburse victims and families for injury-related expenses can take years to process claims.

Although violence is especially concentrated in Chicago’s poorest neighborhoods, people there didn’t apply for compensation at significantly higher rates. These inequalities worsened in 2020, as the pandemic’s first wave took mostly Black victims, hollowing out the same neighborhoods hit hardest by gun violence and the opioid epidemic. Even the city’s vaccine distribution effort left these same communities behind.

Most survivors and families of victims won’t see any form of justice. Data shows that the Chicago Police Department stops investigating about a quarter of nonfatal shootings after just 30 days, citing insufficient evidence. This worsened during the pandemic, with more than a third of cases closed within a month. Data also shows that while Black people are most likely to be shot in Chicago, they are the least likely to see an arrest made in their case.

Our series publishes this week, and will soon be available in Spanish, too. Here’s what we learned:

Part 1: In Chicago’s Roseland Neighborhood, a Mix of Grief and Perseverance

Part 2: Illinois Has a Program to Compensate Victims of Violent Crimes. Few Applicants Receive Funds.

Credits:

The project was written and reported by Lakeidra Chavis. The photography is by Olivia Obineme, Ashlee Rezin Garcia, and Brian Rich. Illustrations are by Lydia Fu. Lakeidra Chavis and Daniel Nass provided data analysis. Daniel Nass also designed graphics and digital production. Gracie McKenzie helped develop community engagement. This series was edited by Joy Resmovits and Miles Kohrman.

This project was produced for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2020 Data Fellowship. The fellowship editor for this project was MaryJo Webster. These stories were published with The Chicago Sun-Times, Block Club Chicago, and La Raza.

[This article was originally published by The Trace.]

Did you like this story? Your support means a lot! Your tax-deductible donation will advance our mission of supporting journalism as a catalyst for change.