Investigation Finds Home Can Be the Most Dangerous Place in a Heat Wave

Molly is one of the recipients of the 2018 Impact Fund, a program of USC Annenberg's Center for Health Journalism.

Other stories in this series can be found include:

How Hot Was It In California Homes Last Summer? Really Hot. Here's the Data

Even in San Francisco, Heat Is Turning Deadly. That's Not Something Colleen Loughman Expected.

Extreme Heat Killed 14 People in the Bay Area Last Year. 11 Takeaways From Our Investigation

It's getting (dangerously) hot in Herre

Being outside can be dangerous, especially at school

What you need to know about LA’s urban heat problem

Sweltering in nursing home, 95-year-old succumbs to heat, as climate endangers most vulnerable

The danger of urban ‘heat islands’

New Rule Would Require Employers to Protect Indoor Workers From Heat Illness

A woman died last year in a heat wave in this normally cool and foggy west side San Francisco neighborhood. But Parkside, like everywhere around the Bay Area, is changing as heat waves last longer and spike higher.

(Photo: Molly Peterson/KQED)

Floyd Ware has survived a widow-maker heart attack, layoffs in the tech industry and living a few doors down from the Grateful Dead. But now he worries that heat—in San Francisco, of all places—is going to kill him.

“I don’t want to exaggerate, but at times it seems all-encompassing, you can’t get away from it,” he says.

Ware, 67, is a wiry man and, for the record, he doesn’t exaggerate. Even during a foggy August, his room at Bayanihan House, south of Market Street, is consistently hotter than outside. When it was 63 degrees at San Francisco’s weather station, it was 81 degrees in his spotless, small space.

Last Labor Day, San Francisco’s record-high temperatures drove him and other residents out onto the street and into the basement of Ware’s single room occupancy building, where large fans blow hot air around rather than cool it. Only leaving his room prevents him from falling seriously ill, he says.

This summer, we put small heat sensors in 31 homes in four counties: Contra Costa, Santa Clara, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. The homes had no air conditioning, and the sensors took temperature readings for three weeks in July, August, or September. In every home, heat was stubborn. It stuck around even as the sun dropped.

And at night, when people’s bodies need to be able to cool off, all the homes we measured let go of heat slowly, staying hotter inside than it was outside—as much as 15 or 20 degrees hotter.

Heat is one of the top public health threats from climate change, according to the state of California. The illnesses and deaths that result from it are preventable. But where people spend the majority of their time, at home, no right to cooling is guaranteed. Public officials around the Bay Area are still figuring out how to warn people and how to respond to heat—both as an extreme event, and as an emerging health threat.

Until they do, a divide is deepening between the cool haves and the hot have-nots.

It’s About Where You Live

Housing is a huge expense that influences people's health. In a heat wave, the most dangerous places can be inside of homes and apartments.

In San Francisco, health officials have concluded that heat builds up significantly in some glassy high-rises and many older residential hotels. Our sensor measurements found that the single room occupancy buildings that once served gold prospectors and seamen stood out as consistently hotter than the weather outside.

Inside these buildings, climate-driven heat already threatens the health and finances of people most vulnerable to it: people like Floyd Ware. After three years in his one-room rental, Ware says his health has gotten worse. He keeps a plastic tub full of medications for his chronic lung disease on a shelf.

“The thing with emphysema is, you can’t get the air out. If you can't get the air all the way out, you can't get the air in,” Ware says. “And the problem with the heat is, it restricts the lungs. So it has an appreciable effect.”

Ware’s doctors advised him not to wait when a sudden emphysema attack comes. Three times in two years, he’s placed an emergency call for an ambulance to Zuckerberg San Francisco General hospital.

Medicare pays most of it, but each time, Ware owes out-of-pocket costs. His social security income pays for his stay in the residential hotel; what’s left over pays for his food and medicine. As a result, Ware says, he has racked up $2,000 in debt.

“I don’t know how I’m going to pay ‘em,” he says.

There Is No Legal Right to Cooling

In-home cooling can reduce the risk of heat illness, according to Linda Rudolph, an expert on health and climate change with the Oakland-based Public Health Institute (PHI). But just one out of every ten Bay Area homes has central air conditioning. Tenants we talked to said they either couldn’t afford to buy a portable AC or couldn’t afford to turn it on.

“Poor people are less likely to have air conditioning,” Rudolph says. “Or they may not have the money to get their air conditioner fixed, or they may live in a rental apartment where the landlord doesn't want to get it fixed.”

Or it may be that window units only do so much.

At 5:30 p.m. one August evening, it’s still over 90 degrees in Mario Rodriguez’s San Jose apartment—the first floor of a complex with few trees and a scrabbly lawn, along busy North Main street.

Rodriguez has low blood pressure and is on constant oxygen, for lung trouble.

“When it gets hot I get kind of dizzy,” he says. “I get tired and I have to sit down for a few minutes. Or I start sweating and then I start fainting out.”

Rodriguez bought a window air conditioner from a friend for $75, even though he knew it would raise his electric bill. The unit cost him an additional $75 when his rental manager required him to install it with plexiglass around it, rather than plywood.

He added the air conditioner during the period when we were measuring heat in his apartment. But even on days when he ran the it, indoor temperatures peaked at 10 degrees hotter than outdoors.

Habitability, under federal and California law, requires only that water run freely, and that heating be available. New York and some Canadian cities have considered making in-home cooling a right. But in Sacramento, the idea of a tenant’s right to cooling has died a quick death.

Mario Rodriguez' San Jose was 10 degrees hotter than outdoors, even when he turned on his window air conditioner. (Photo: Molly Peterson/KQED)

Cyndy Comerford used to work for the San Francisco Department of Public Health, where she analyzed housing and heat. Now, she directs climate programs for the city of San Jose.

“I really do think that government potentially has a role in making sure buildings are safe,” Comerford says. “We do that structurally. We make sure they’re not too cold. We ought to make sure they're not too hot, too.”

And keeping buildings cool isn’t only about air conditioning, as researchers and urban designers have concluded.

How To Cool an Old Building

Well-designed neighborhoods once took the landscape into account, says Stephanie Pincetl, a sustainability researcher at UCLA. They had less concrete, and were cooled by breezes and natural shade, including from trees.

California has amnesia about how to combat heat in cities, Pincetl says, having forgotten resilient city design when development boomed and ushered in cheap housing.

“Older buildings are less well insulated,” she says. “Really, what we need to do is have much better buildings.”

Pincetl argues the state could adopt building codes that promote passive cooling, and provide incentives for owners to harden buildings against heat. Landlords could improve insulation, add vegetation, and plant climbing vines to cool off old apartments.

Public health officials, epidemiologists and researchers like PHI’s Rudolph argue that health systems and environmental conditions are connected. They say California should plan not just for acute heat disaster, but for lasting change.

That means planting trees, promoting cool rooftops, and even investing in street surfaces that reflect heat away from the ground, Rudolph says, in order to reduce the maximum temperatures in neighborhoods.

“Because otherwise," she says, "we essentially won't be able to respond and adapt adequately.”

Any of those ideas demand coordination among multiple county and local departments. Few laws require this work, and little funding supports it.

“These climate-related health problems—really no one else is going to pay attention to them,” says Rudolph. “But the local health departments frankly need help.”

‘A Double Whammy’

Rose Basulto lives on a treeless street, a block from state Route 4. Almost every day during three weeks when we measured the temperature in her home, it was hotter inside than out. In her living room, the temperature peaked over 100 degrees, eight times in three weeks.

For the 37-year old Basulto, heat made it hard to think - and move. At night, when it could be almost 80 degrees inside, she found it nearly impossible to sleep.

“If it’s like that again, I don’t think I can make it through another summer.”

Heat made her asthma worse. It exacerbates cardiovascular, respiratory and renal conditions, and places stress on people with diabetes and obesity.

“When the nighttime temperatures don't go down, which is what's increasingly happening with climate change,” says Rudolph, "it's harder for them to get that kind of physiological rest period."

Basulto and other renters we talked with around the Bay Area say they’ve found few simple solutions to living in warm homes—other than to leave them. At least half a dozen people who described housing conditions they linked to health problems decided not to allow us to document heat in their homes, even anonymously, for fear of angering a landlord, or destabilizing a precarious housing situation.

Arizona heat scientist David Hondula has noticed the same thing in his research.

“There's this undercurrent of a sense of being stuck with the conditions the way they are,” he says.

In a couple of years, PG&E will implement “time-of-use” pricing, charging for electricity based on when demand peaks—which is late afternoon, as people return home from work and school.

And according to our measurements inside homes, it’s exactly when indoor heat rises, soaring past outdoor temperatures.

Time-of-use pricing will make cooling older homes cost more for people who already can’t afford it, according to Pincetl.

“And so they're going to get the double whammy,” she says.

Warning People Is the First Step

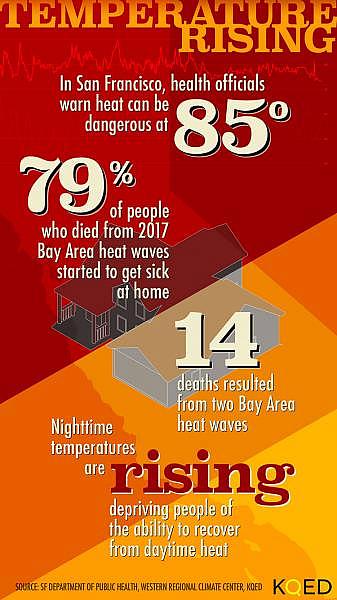

Across the Bay Area, and across the state, the time and manner in which counties choose to warn people and respond to heat varies. Contra Costa County is working on an emergency response plan for heat. In 2015, its public health department concluded that excessive heat means temperatures above 85 degrees along the western bay side of the county, and above 96 on the east side. Last Labor Day, when heat killed 14 people around the bay, San Francisco declared a heat emergency; San Mateo County did not.

San Francisco has studied its risk from warmer temperatures, and adopted an aggressive policy to send warning notices at 85 degrees. And the city is going even further, with hyperlocal training to help neighborhoods be ready for natural disasters. In a heat wave, the Neighborhood Empowerment Network would connect residents to each other, to prevent bad health outcomes.

The network’s director, Daniel Homsey, drives among the nook and cranny communities on the south and east side of the city, parking us in Dolores Heights, a patch on the eastern slope of Twin Peaks that gets plenty of sunshine.

San Francisco waives permit and street closure fees for 280 block parties, called Neighborfests, each year. Every Neighborfest spread, just like every city block of a city, has its own personality: in Dolores Heights, Beyonce and Madonna blare from speakers at one end of a block. At the other, kids play cornhole.

On tables next to several grills, an array of salads - Greek, quinoa, green, and fruit - stands sentinel alongside burgers and hot dogs. Homsey points out a barbecue buffet isn’t too different from how a neighborhood might set up a feeding station in a disaster.

The city’s secret mission with Neighborfest, isn’t just to get neighbors to swap salads; it’s to get people used to coming out of their homes to help each other. Neighborfest volunteers lead conversations that establish communal inventories—who’s got a cool basement or air conditioning, propane tanks or water supplies.

And neighbors themselves are building phone trees as a means to look out for each other, says Maria José González-Salido, a Dolores Heights block captain.

“Like, I know they have children, I know someone else has an elderly person, they know I have my mom,” she says, nodding at different homes. “It’s a good community thing to have these parties and get to know everybody, right?”

Making his way to another Neighborfest, Homsey pulls over to poke around a garage sale; he’s always on the lookout for disaster supplies, like coolers and chili pots, to donate to communities.

“I’m a hoarder in recovery,” he says, half-laughing, “and I’m using disaster preparedness to focus my investments better.”

In the 19th century, the nickname for this hilly patch of land on the southeastern side of San Francisco was Little Switzerland: it was a vacation spot, with plenty of cows, and little fog.

Now it’s Glen Park, and its homeowners, including Fran Link, suffered last year for days in a row from heat.

“We’re not used to that,” she says.

Homsey asks Link if her home gets hot. Yes, Link answers; the turreted house faces south, and west, with big bay windows and no air conditioning.

Homsey tells her his aunt didn’t have AC, either. She lived nearby, and died in her home twenty years ago, during a heat event. Homsey’s father found his sister, several days later, on her bed.

"Rather than make a decision that was rational, which is, 'It’s really hot at my house, I’m going to downstairs where it’s cooler,'" Homsey says, “she’s like, 'I’m really tired, I’m going to go lie in my bedroom.' She lay down and she never got up."

Homsey often thinks of his aunt as he does this work. He says San Francisco's program is helping strangers become neighbors. After Link talks to him at her garage sale, she heads over to the block party to hear a live band; later in the month, she goes to a neighborhood training about how to respond in a bleeding emergency. Meanwhile, Homsey is spreading the gospel of grilling and readiness by working with Santa Rosa and Oakland. They want Neighborfests too.

That’s resilience, he says. “It’s about building on the traditional ethos of being a good neighbor, and caring for those around you, even if you don’t have an immediate relationship with them.”

Every heat death is preventable; it’s a core belief for Homsey and for public health experts.

But right now, few systems, laws, or policies require centralized preparedness against heat. Illness related to extreme high temperatures is poorly tracked and underreported. Cooling hot homes, and hot neighborhoods, isn’t easy. And little public funding helps pay for responding to climate-related health issues.

As the danger of heat grows, Californians are still pretty much on their own.

Editor’s Note: Amel Ahmed contributed to this story. Miguel Hernandez and Osvaldo Pedroza dropped off and picked up sensors for houses in southern California, and provided language translation in the field.

This reporting is supported by a grant from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism Impact Fund.

[This story was originally published by KQED Science.]