Judges aim to halt central Arkansas plan on youth probation

Support for Curcio’s reporting on this project also came from the Fund for Journalism on Child Well-Being, a program of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism at the University of Southern California.

Other stories in this series include:

As kids languish in lockups, rehabilitation chances fade

Youth advocates, state disagree on need for independent oversight

Youth miss out on school, mental services in lockups

After scandals, 1 Arkansas youth jail to stop incarcerations

Promise of family services misses the mark in Arkansas

Youth jail to stop incarcerations

Files reveal dozens of violations by firm set to manage Arkansas' youth prisons

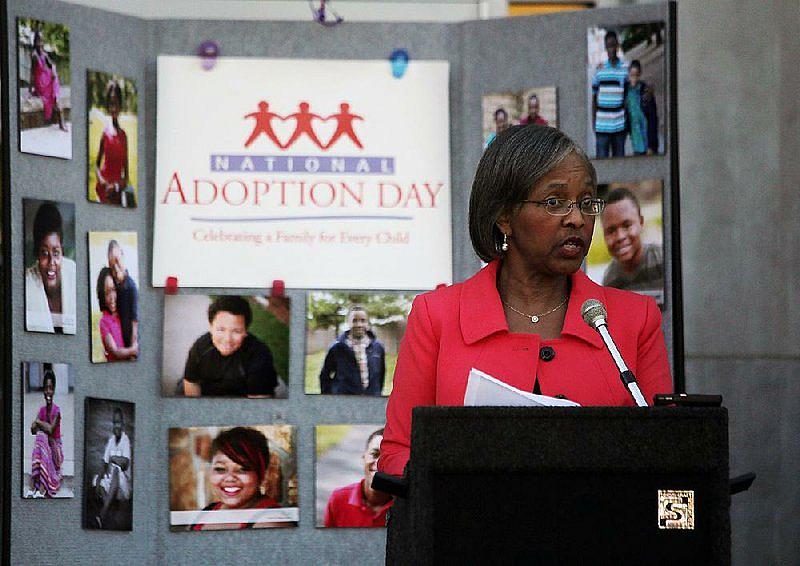

In this file photo Circuit Judge Joyce Warren speaks at the Pulaski County Cuvenile Court Thursday, November 17, 2016.

All 17 Pulaski County circuit judges are trying to block the county's attempted takeover of the court's juvenile probation department, records show.

On Tuesday, the Pulaski County Quorum Court is scheduled to vote on creating a $68,200 director of juvenile-justice services position overseen by County Judge Barry Hyde, the county's chief executive. The new director would manage the county's juvenile probation department, including updating its policies, and oversee other youth-justice programs.

Hyde has said that he thinks the juvenile probation department, currently managed by three circuit judges, needs his office's help improving how it handles and organizes cases.

Hiring a director would lower probation lengths, he said, even though circuit judges set probation terms.

Judges, however, contend that Hyde's proposal violates their legal authority. The judges say they will challenge Hyde's move in federal court if the Quorum Court supports his proposal.

Hyde has cited two studies of the county's juvenile-probation system that pointed to poor organization and management as the reason for seeking control of the program.

At an April 28 Quorum Court budget committee meeting, Circuit Judge Joyce Warren described Hyde's plan as idiotic. It would not only infringe on judges' statutory obligations to oversee juvenile probation, but would also make judges less connected to the cases of at-risk children they preside over, she said.

"It takes a village" to help troubled youths, she said. "But it takes a competent village, not a village of idiots. And we're not a village of idiots."

The county's two other juvenile-court judges also expressed dismay at the proposal.

"I think a lot of these responsibilities are way overreaching," Judge Patricia James said of the proposed new county post.

"I'm not over at the assessor's office telling them what to do... Do we all work together in different areas? Sure we do... You can't not work together. But that doesn't give me authority to go into a different department and tell them what to do."

"I been in this spot 25 years. I'm getting ready to retire, so this may be the last time I might be up here," said Judge Wiley Branton Jr. "In all these 25 years, I've been respected by this body, I've also shown respect to this body. Never, before now, have I felt so disrespected by this administration.

"Not to you personally, but by the county judge," Branton said.

During closing remarks at the budget meeting, Hyde called the director position "badly needed" and asked for the Quorum Court's approval "so that our data-driven juvenile justice reform can continue moving forward and not be stuck at this dead end.

"The county stands ready and fully prepared to fight this battle in court on who has this right to hire and fire," he added. "That's what the argument is about here."

Arkansas law says the county judge is responsible for the hiring and firing of county employees "except those persons employed by other elected officials of the county." State statutes also describe juvenile probation and intake officers as assigned to elected circuit judges who "serve at the pleasure of the judge or judges."

Although Hyde's title is county judge, he is primarily an administrator under state law. He is the custodian of public buildings and county property and presides over the Quorum Court -- an elected body similar to county commissions in other states. The Quorum Court, with the county judge, levies county taxes and sets aside funds for county operations.

The debate over statutory authority continued after the meeting.

On May 17, 6th Judicial Circuit Administrative Judge Vann Smith sent a letter to Hyde -- which noted that he spoke for all 17 Pulaski County circuit judges -- that said there were "grave concerns that any unilateral action by the Quorum Court will interfere with the Administration of Justice."

In the letter, Smith also asked that he and other judiciary members be asked to express their concerns to the full Quorum Court at the upcoming meeting.

A county spokesman didn't answer whether the Quorum Court would hear the judges. But a May 14 letter from Hyde to Smith says that "public discussion on an item is typically provided for in committee meetings, as was done in this case. The full Quorum Court may discuss this item as it sees fit."

'NOT PERSONAL'

Hyde has sought management of the juvenile-probation department since as early as February.

Back then, he tried through the Legislature, pushing a draft bill backed by Sen. Will Bond, D-Little Rock. All three juvenile-court judges opposed that proposal, which was never filed.

Bond later told the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette that he balked once he learned "there was never any consensus that developed" on the proposal. Bond said Hyde didn't convey that there was debate surrounding the issue when first trying to file the bill.

Warren also said that Hyde wasn't upfront about his proposal.

"He needs to be honest and tell the truth," she told the newspaper in an emailed response on Monday.

She criticized his account of the judges' working relationships and their knowledge of the legislative process at the Quorum Court committee meeting. Hyde had told committee members that the judges have "never been able to get along" and that they were unable to distinguish a draft bill from a filed proposal.

But Hyde insists his plan is about juvenile-justice reform, and that it's "not personal."

He cited a pair of 2017 reports that found the county's juvenile-probation system needed an overhaul, mostly because of poor organizational structure and management, not enough data-keeping and outdated training materials.

One report, conducted by the Washington, D.C.-based Center for Children's Law and Policy, found that 54% of Pulaski County juvenile jail admissions in 2016 were for probation violations -- "a percentage that is among the highest that we have seen."

The other report, from the Boston-based Robert F. Kennedy National Resource Center for Juvenile Justice, recommended that judges update probation workers' job duties and descriptions.

"Without a current manual or mission statement to guide practices, workers don't know what was expected of them," the report said.

"The staff is clearly frustrated and demoralized, but anxious about the possibility that potential change will be worse than the status quo," according to the study. "While everyone acknowledged there was a problem, no one was willing to discuss details or methods for resolution."

Other recommendations made in the Kennedy center report, such as assessing a child's risk level before incarceration or how children are assigned to certain probation officers, have already been adopted by the circuit judges.

An investigation by the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette last March also found these problems weren't confined to Pulaski County.

The newspaper found that many children placed in juvenile probation didn't get needed help because of overworked officers and circuit judges who didn't change the way they handled cases. Outside of Pulaski County, judges used probation to discipline, rather than rehabilitate, young offenders -- going against what national research indicates works best, the newspaper reported.

[This story was originally published by the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette.]