Kern County’s Opioid Users Lack Access To Much Needed Treatment

This story was produced as part of a larger project led by Kerry Klein, a participant in the USC Center for Health Journalism's 2018 Data Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

Four Years Sober, Recovering Heroin User Shifts Focus To Saving Other Lives

It Used To Be Kern County's Opioid Epicenter, But Oildale May Be Cleaning Up

To Bakersfield Cops, Concern For Opioids Grows - But Meth Is Still King

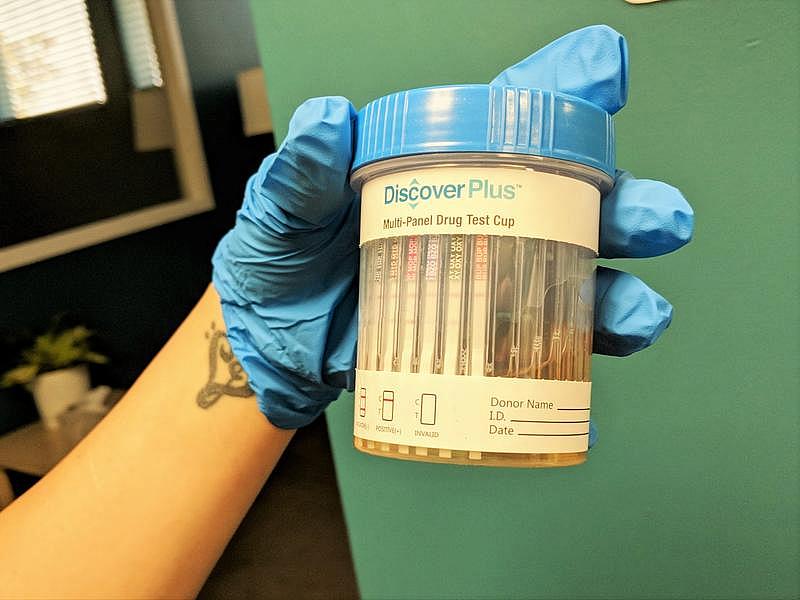

Urine testing is part of a medication-assisted opioid treatment program in Bakersfield known as Groups. By some estimates, as many as three-quarters of Kern County residents with opioid use disorder are unable to access the treatment they need to recover.

KERRY KLEIN / VALLEY PUBLIC RADIO

The sun is fading on a Wednesday night and people are trickling quietly into an office behind an unassuming parking lot in Northern Bakersfield. Inside, bright yellow chairs and plastic flamingoes lean against turquoise walls and Tom Petty’s on the radio. A chipper administrative assistant named Mary Lora greets people as they walk through the door.

Chatting with Lora through the glass is Larry Bostick, a scruffy redhead leaning against the little white check-in counter. Lora asks him how he’s doing and he smiles underneath his skater cap. “Really good,” he says. “I haven't felt this great in the last two years.”

He says he’s feeling good because he’s clean—off heroin and pills. “Fully on sober, I have been going on 2 months, which I mean is good,” he says. “It's not great, but I feel honestly that this is it for me.”

The “this” he’s talking about Groups, the drug recovery program where we’ve met tonight. Its Bakersfield location opened its doors last May. The goal: Reduce dependence on opioids like heroin, oxycontin and fentanyl, and prevent deaths from overdosing. Although California is not at the epicenter, the San Joaquin Valley has been hit hard. And the problem has reached a crisis point nationwide: For the first time ever, the National Safety Council has estimated that the odds of dying in a car accident have been eclipsed by those of dying from an opioid overdose.

At Groups, people recovering from opioid abuse attend a group session once a week, kind of like Narcotics Anonymous. But here, they don’t just get a support system; they also get a prescription for a medication that helps them kick the drugs. Every week, they pee in a cup to show they’re taking their meds and nothing else. And it’s pretty affordable: It typically costs $65 a week cash, plus the cost of the medication, but a new state grant allows most clients to attend for free. “It works for me,” says Bostick. “Other programs may work for other people, but this right here I know works for me.”

About five and a half years ago, Bostick was hit by a car. He says he was pushed into the back of a public bus and he went through the car’s windshield. “I had reconstructive surgery on my face, broken arms, surgery to have teeth pulled out of my hand,” he says. “I broke my leg, my foot, my sternum, a couple ribs.”

After such a horrific accident, he was prescribed lots of painkillers—mostly opioids. “The dilaudid, morphine, all that kind of stuff, you know,” he says. “I realized: Ooh, I kind of like this.”

His prescriptions ran out, but he found a way to get more. He couldn’t stop even when he was out of money, so he turned to a cheaper alternative: Heroin. He says it took a few years for him to realize how deep he’d sunk. “Finally hit rock bottom, got my son taken away from me and everything,” he says. “I knew I needed help.”

So he found Groups. The program, whose motto is “Recover Together,” offers what’s known as medication-assisted treatment, or MAT. Methadone is one kind of medication used in MAT, but at Groups, the drug is buprenorphine. It’s kind of like a nicotine patch for quitting smoking: Buprenorphine is an opioid, but it works differently than other drugs, and doctors taper the dose over time so patients can eventually stop. “You don’t get high off of it,” says Bostick. “And it blocks your receptors, so if you do go and use on the streets, it just makes you sicker than heck.”

Research increasingly shows that MAT programs work better for recovery than trying to quit cold turkey. In Baltimore, for instance, a study showed a correlation between buprenorphine and a drop in overdose deaths from heroin.

In Kern County, though, MAT is hard to find. Kern has one of the biggest treatment gaps in the state. The Urban Institute estimates nearly 8,000 people in the county suffer from opioid use disorder, and almost three quarters of them lack access to treatment. Estimates from the county public health department suggest the gap could be even larger. “If every single bed and chair was full in this entire county, there would still be a huge amount of people who needed treatment and couldn't get it,” says Ariel Turner, a substance abuse counselor with Groups.

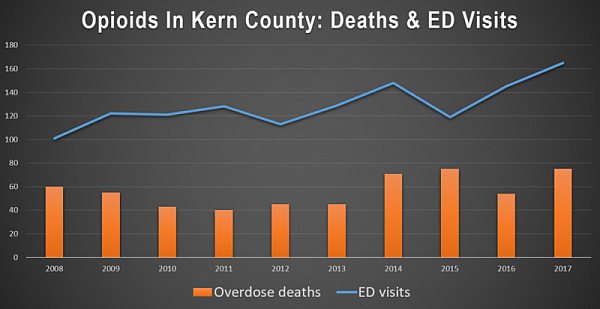

CALIFORNIA OPIOID OVERDOSE SURVEILLANCE DASHBOARD

The Bakersfield clinic is Groups' third location in California, following dozens already operating in the Midwest and on the East Coast. “Groups' mission is to go into rural areas or locations that have a lack of access to treatment,” Turner says—and Bakersfield fits that bill, despite the fact that it’s the ninth largest city in California. “Bakersfield is actually the biggest city/town they've gone into.”

Turner says treatment gaps here are partly a result of persistent stereotypes and outdated attitudes toward addiction. Many view users as degenerates and criminals, and feel that buprenorphine and methadone only enable them to keep using.

Javier Moreno used to feel that way, too—but now he’s a regional manager for Aegis Treatment Centers, the biggest program offering MAT in the state. “Once I saw the medication work, I became a believer and an advocate ever since,” he says. “Medication assisted treatment is highly effective. I get to see it every day.”

Another reason patients have a tough time accessing medication is so few providers offer it. For one, they have to either work at clinics like Aegis or get a special waiver from the federal government. But as of a year ago, less than 2% of all prescribers in the county were waivered. Waivers do require extra hours of training, but Moreno says doctors are overly concerned about how disruptive these patients can be. “You do have your difficult patient or two, but for the most part it’s very pleasant and rewarding to be able to treat our patients,” he says.

Plus, health officials and law enforcement are already stretched thin taking care of another long-standing drug problem: methamphetamine.

But the opioid crisis? It’s urgent. In the last decade, opioid overdoses have led to more than 1300 emergency room visits and killed over 560 people in Kern County. “It just consumes your whole life,” says Larry Bostick. “It consumes everything. It just destroys. That's all it does.”

For Bostick, recovery has not been a straight shot. Groups is his third attempt at sobriety, following stints at a methadone clinic and at a residential facility. But in the two months he’s been here, he says he’s tangibly changed his life. “My mom talks to me again, my family's back in my life, I’ve got access to my son now,” he says. “It's been a complete 180.”

In today’s session, he sees a familiar face: A guy he met through his former heroin dealer. They sit in front of a sign reading “Groups: Recover Together” and chat about healing. They talk about how buprenorphine works—“it keeps you honest,” Bostick says—and joke about how much more money they have without feeding a drug habit.

As they get up to leave, the men find each other on Facebook and embrace in a big hug. “If you want to talk about anything, have any questions or feel like using or something, give me a call,” Bostick tells him. “We’ll get through this together.”

[This story was originally published by Valley Public Radio.]