Thousands are waiting in jail for state hospital beds. Is help coming?

This project was produced as a project for the USC Center for Health Journalism's 2021 National Fellowship.

Other stories by David Barer include:

Mental competency consequences: the hidden, unreliable data Texas tracks… or doesn’t

Wrong races, hidden names among data challenges our team faced with jail mental health project

Austin court’s redirection of those committing low-level crimes could be saving taxpayer money

Mental Competency Consequences: The Hidden and Unreliable Data Texas Tracks — Or Doesn't

State of Texas: Leaders consider ‘consequences’ of not tracking state hospital waitlist data

‘Horrifying’ wait times for state hospital beds, official says

A state hospital death in restraints and seclusion: What happened to Justin Reeder?

Jail waitlist for mental health help hits new record. This plan proposes a statewide fix.

State mental hospital backlog grows, new record exceeds 2,500 waiting in jail

Despite waitlist record, leaders keep pushing ‘Eliminate the Wait’ plan for state hospitals

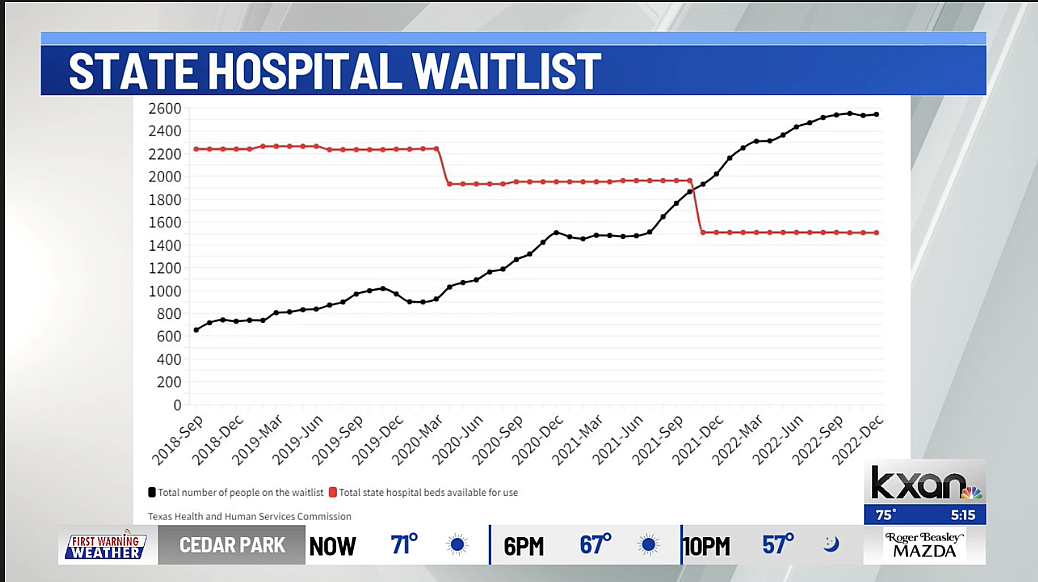

AUSTIN (KXAN) – The waitlist to enter Texas’ mental hospitals remains near a historic high, with thousands of mentally incompetent people sitting in jail for months or years in need of treatment. But after years of steady waitlist growth, state data shows a glimmer of hope for an eventual turnaround.

Officials with the Health and Human Services Commission advisory committee said Wednesday the waitlist has plateaued for the past five months and new efforts to shore up staffing could help reopen offline bed space. Also, county-based efforts – like one in Williamson County – to provide mental health treatment in jails could help stem the tide of people put on the waitlist.

As of December, there were 2,545 people on the waitlist. It was taking an average of 699 days to admit people to maximum-security state hospital beds and 227 days for non-maximum-security spots, according to data released by the Joint Committee on Access and Forensic Services.

Committee data shows only 66% of the state’s 2,500 hospital beds are available to use. The bed shortage has steadily worsened over the past three years. Understaffing now accounts for almost all offline beds, state hospital officials said.

People are placed on the waitlist after being found incompetent to stand trial and ordered to a state hospital for competency restoration. Mental health and legal experts, like attorney Keith Hampton, said more needs to be done immediately.

“They’ve got a plan that will bear fruit in two or three years, but, in the meantime, we have severely mentally ill people who’ve been ordered into the hospital and instead are simply languishing in our jails.”

The legislature will consider bills that could impact the waitlist. One law brought by Hampton to a Central Texas lawmaker would set a three-week deadline for transferring people out of jails.

Stephen Glazier, a member of JCAFS representing the Texas Hospital Association, said the committee has collected data that shows people are taking longer to get restored to competency.

‘Length of stay’

Glazier’s group analyzed data from 2019 through 2022. They discovered the pool of people on the waitlist skyrocketed over those four years, while the inflow of people rose only slightly.

“Why is that?” Glazier asked. “It, of course, is length of stay.”

The average length of stay in the state hospital system has gone up significantly in the past four years. For maximum security beds, the average length of stay rose from 195 days to 274. For non-maximum-security beds, that average increased from 204 days to 472, Glazier said.

“If we can get that length of stay down, we might actually be able to see the list starting to come down again,” Glazier said.

Lawmakers, criminal justice experts and mental health advocates are hopeful the legislature will tackle the problem and dedicate some of the state’s ample surplus to solve it.

21-day deadline

State Rep. Gina Hinojosa, D-Austin, filed HB 479 to require the state to move incompetent people from jail to a mental health facility within 21 days of a court ordered commitment. Hinojosa’s office said the bill was brought to them by longtime defense attorney Keith Hampton.

Hampton has deep experience representing mentally incompetent defendants. He said the 21-day timeframe already exists for people found insane.

Problems caused by the waitlist extend far beyond the “inhumanity” of leaving mentally ill people in jail for years, he said.

When a person is found incompetent, their case cannot proceed until they are restored to competence. A defendant can’t have a meaningful conversation with their attorney. Cases languish without resolution and can fall apart.

“You’ve got to understand that the entire system stops,” Hampton said. “That means everybody is frozen in time including the defendant, including witnesses, including victims and survivors of victims.”

The number of people waiting in jail for a state hospital bed has steadily grown for years. Meanwhile, the number of available beds has dwindled.

KXAN has reported on the problem for years.

KXAN’s report “Mental Competency Consequences” investigated the state’s unreliable and hidden data used to track people on the waitlist. KXAN found at least a dozen cases of incompetent individuals dying in jail before being transported to a state hospital for treatment. No government agency tracks and identifies those deaths.

In a 2020 report, “Locked in Limbo,” KXAN profiled Ben Bush, who spent months in Williamson County jail spiraling further into mental illness while unable to get transported to a state hospital.

One of those deaths was 24-year-old Daniel McCoy, who was in Williamson County jail at the same time as Bush in 2017. McCoy suffered from schizophrenia and died in his jail cell after his health slowly deteriorated for months, according to a federal lawsuit.

Now, Williamson County officials want to turn part of the jail into a treatment facility.

Jail-based competency restoration

On Tuesday, Williamson County commissioners discussed creating a jail-based competency restoration program. In such a program, a person found incompetent to stand trial would receive psychiatric treatment in the jail and wouldn’t be transferred to a state hospital.

Williamson County Commissioner Valerie Covey said they have large mental health population in the county jail, and those individuals are stuck because of the state hospital backlog.

State Sen. Sarah Eckhardt, D-Austin, is sworn in on Jan. 9, 2023, for a new term. (Courtesy: Office of Sarah Eckhardt)

“They are supposed to be able to go to a state facility,” Covey said. “We are seeing a delay in as much as several years, and that is just not right, and that is not OK in Williamson County.”

The county has funding to begin the program in the spring, and a special jail pod for it, she said.

Andrea Richardson, CEO of Bluebonnet Trails Community Service, said they will be adding more psychiatry and board-certified wrap around services. Bluebonnet Trails is the county’s local mental health authority.

“These are going to be persons that are actively receiving mental health treatment while in the jail in a specialized pod that are working together for competency,” Richardson told county commissioners. “The goal is to move them quickly and restore them to competency and get them to trial more quickly, rather than just waiting in jail and decompensating.”

Harris County has a jail-based competency restoration program. Proponents say it can be effective and help reduce the number of people waiting for a state hospital bed. On the flip side, many mental health and criminal justice experts have rejected the programs.

In a 2021 interview, State Sen. Sarah Eckhardt, D-Austin, said jail is a “completely inappropriate” place for mental health treatment.

“These individuals have not yet been adjudicated. They need to be in a healthcare setting,” Eckhardt said. “I have said it over and over again: we should not be using our jails as mental hospitals”

Eckhardt filed Senate Bill 1346 in 2021. That legislation would have created an Office of Forensic Services within HHSC to ensure “a strategic statewide approach to the provision of forensic services.” The bill was created out of JCAFS recommendations, but it didn’t pass. Eckhardt said many of the recommendations have been taken up by HHSC’s forensic director, including the redesign of the Austin State Hospital, which the 86th Legislature appropriated $165 million for, she said.

Eckhardt has not refiled the bill. She said the idea of a forensic office is “not off the table,” but she’s hopeful the state and legislature can address the waitlist and HHSC’s chronic understaffing with less bureaucracy.

“We are at a point of opportunity with the almost $33 billion surplus,” Eckhardt said in a statement. “We must use these dollars wisely and in-part invest in our state hospital system to assist in sorting through the backlog and establishing processes to prevent leaving Texans stuck in limbo like this in the future.”

[This article was originally published by KXAN.]

Did you like this story? Your support means a lot! Your tax-deductible donation will advance our mission of supporting journalism as a catalyst for change.