Lost, Stolen, Sold: S.F. Violates Homeless Property Policy

This story was produced as part of a larger project led by Nuala Sawyer, a participant in the 2019 California Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

Drug Users Face Extra Health Challenges With Uptick in Homeless Sweeps

S.F. Sees New Success in Treating Homeless People with Hep C

Keeping the Homeless Out of Sight Makes Their Lives More Dangerous

Heather Lee stands outside a closed gate at the Public Works yard after attempting to reclaim her belongings.

(Photo: Leslie Dreyer)

It’s been more than a year since interim-Mayor Mark Farrell demanded that the City of San Francisco dedicate more resources to clearing the streets of homeless people’s belongings, and seven months since current Mayor London Breed proudly announced a 34-percent reduction in tents on sidewalks. In the past two years, the city has sought to eliminate the visual evidence of homelessness in San Francisco, even creating an entirely new department — the Healthy Streets Operation Center (HSOC) — to manage all 4,000 of the 311 complaints that come in each month about tents, shopping carts, and people sleeping on sidewalks. Each time a call comes in, a team is assembled depending on the issue — sometimes it’s Department of Public Health Employees and the Homeless Outreach Team, but more often, it’s the San Francisco Police Department and the Department of Public Works that handle these incidents.

Despite claims from city officials that the program is a success, the nightly waitlist for shelter beds hasn’t dropped below 1,000 in more than a year. But instead of finding beds for people, the city has been sweeping their belongings off the streets, leaving them to fend without shelter or medication. In the meantime, a circus takes place as people attempt to get their seized belongings back from the city. Items are thrown out, damaged by mildew, lost, and even — allegedly — stolen by Public Works employees. In all, fewer than 20 percent of what the city takes gets returned to its owner.

The policy the city created to manage homeless folks’ belongings isn’t that bad — they can’t take items unless they’re unattended, must give people ample time to break down tents and tidy up belongings, and have to make anything seized available for pickup within 90 days. Once Public Works bags and tags what it takes, property owners receive a receipt they can use to reclaim their belongings from a warehouse off Cesar Chavez Street and Bayshore Boulevard.

But speak with any homeless person who’s tried to go through the process of visiting the warehouse to reclaim their belongings, and cracks in the system immediately appear. There are no signs outside the gate to the yard to direct people where to go, and often, no workers in sight. People are told to wait on the sidewalk outside the yard for their items to be brought out, but hours later, no one shows up.

In one rare instance — due to a lack of staffing at the gate — artist and organizer Leslie Dreyer and homeless advocate Couper Orona captured video footage of the inside of the yard when they stopped by to help a woman named Heather Lee get her belongings back. The scene is shown in episode two of Stolen Belonging, a multi-medium arts project that features an online video series documenting items lost during homeless sweeps. After finally finding someone to take a description of Lee’s items, the trio is told it’ll be out in 20 minutes. An hour and a half later, while it poured rain, the gate was closed and they gave up and left.

“This is what they’ve been doing to everyone I’ve talked to,” Lee says. “Making them wait. And then they end up leaving, which is what they want them to do. I don’t believe they have my possessions at all.”

Orona agrees.

“Twenty-three people I know have come out here, and they haven’t gotten one item back,” she says. “They come out here, they wait. There’s no signs, nothing saying, ‘Oh, please call this number.’ There’s nothing.”

“The main demands coming from everyone we’ve interviewed is to stop the sweeps,” Dreyer says, referencing the dozens of people her team spoke to for Stolen Belonging. “Let them maintain their survival gear and medications. Let them hold onto the only things they have left in the world that give them some sense of security and stability. Let them exit homelessness instead of driving them further into it. They have a right to decent housing, and this rich city can certainly find a way to afford it — if they would just prioritize people’s needs over profit.”

In an effort to identify exactly what’s happening to people’s belongings, SF Weekly obtained every bag-and-tag form the city has issued from October 2016 to March 2019. There are hundreds of them, loosely organized by date and scanned into a dozen disorganized PDFs. At times, the tags are impossible to read. The handwriting is lopsided, many sections are left blank, and much is redacted.

Nevertheless, there are still stories hidden behind the scrawls: wheelchairs, walkers, tents, laptops, and cell phones are listed on the hundreds of pages of tagged items. Sometimes descriptions of the items are short — “1 bag” reads a tag from Feb. 19 of this year. Others are oddly intimate, like the “wicker basket with nail polish and lipstick” seized two days later.

And the geographic scope of the sweeps immediately becomes evident. On Feb. 2, when a massive atmospheric river that moved through the city brought two inches of rain in 24 hours, workers picked up a number of things. They acquired a tent, a gray bag, and a black plastic bag from San Bruno Avenue and Alameda Street, a black suitcase and a black backpack from King and Seventh streets, and a wheelchair from Market and Eighth streets.

While much of the stuff could seem worthless to the naked eye, inside the plastic bags and tents are people’s entire lives. Stolen Belongingdocuments this, as people tell stories of losing their loved ones’ ashes, family heirlooms, photo albums, medication, and shelters. And amid the survival gear and personal effects are items that could easily be turned around. It’s these items, a former Public Works employee says, that are often stolen and resold.

This former employee wished to remain anonymous, but SF Weeklyconfirmed that he was recently employed by the Department of Public Works. He told his story to the team behind Stolen Belonging.

“They’ll just go to the big dumpster and start unloading it, and whatever that looks good to them they go sell it on the weekend and try to make money off it,” he said in an interview earlier this spring. “Electronics, laptops, phones. Everything. Whatever they can get.”

According to this former employee, many of the items are sold at the 16th and Mission flea market on weekends.

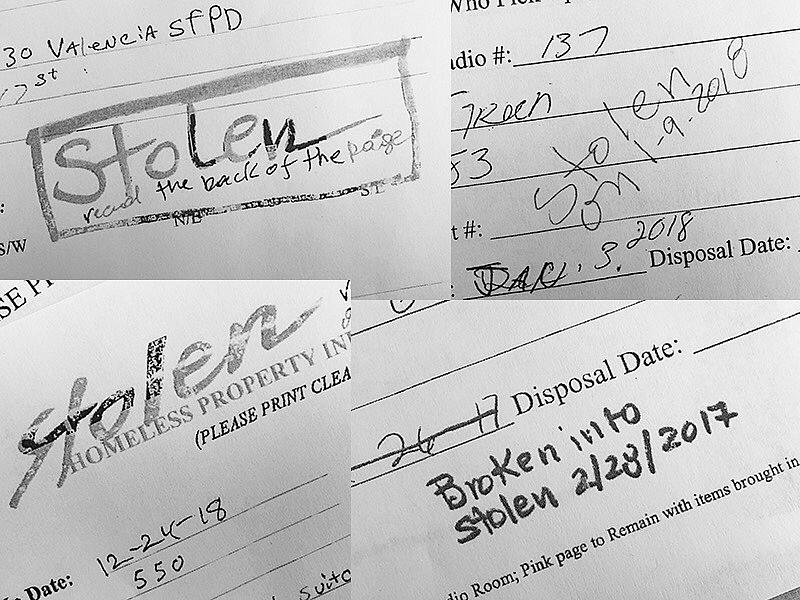

Just a few of Public Work’s bag and tag forms stating that items had been stolen from the yard. (Image: SF Weekly)

Public Works’ paperwork could corroborate his statements. More than a dozen forms from the past two years have “stolen” scrawled across the top. On Dec. 19, 2018, one bag was taken from outside 899 Waller St. The owner apparently tried to pick up the bag two days later, but couldn’t. “Stolen?” the note reads. “Not found inside or around the cage.”

Others are more incriminating. Several tagged items picked up on Dec. 23, 2018, went missing almost immediately. “Stolen items, taken from the front of the cage and stored behind container near cage,” read a note written on one of the forms three days later. “Items were taken and empty bag tags and pink form were left.”

The Department of Public Works confirmed with SF Weekly that thefts have taken place at the yard, but claim they were committed by outsiders.

“We have had several incidents over the years where people from outside of the organization have sneaked into the Operations Yard when the gate was opened for passing vehicles or cut through the security fence and have broken into the bag-and-tag storage area, and each time we have filed police reports,” spokesperson Rachel Gordon says. “We recently brought in a more secure metal container, which has helped keep the goods secure.”

In regard to thefts happening internally, Gordon says they have no records of such instances.

“We of course would investigate any specific allegation and take appropriate disciplinary action if an employee is found to have stolen items from bag-and-tag,” Gordon says. “That behavior, if proven, would be unacceptable.”

The seizure of people’s belongings by the city of San Francisco is egregious, not least because the sweeps themselves have been deemed illegal. An April ruling from the Ninth Court of Appeals banned the enforcement of sweeps if no shelter is available. “The panel held that, as long as there is no option of sleeping indoors, the government cannot criminalize indigent, homeless people for sleeping outdoors, on public property, of the false premise that they had a choice in the matter,” it reads.

Combined with the repetitive seizure and misplacement of people’s belongings, it’s likely just a matter of time before a suit is brought against the city and county of San Francisco for doing just that.

[This story was originally published by SFWeekly.]