Many Pacific Islander Patients Have To Move To Get Life-Saving Access To Dialysis

This story was produced with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 Impact Fund for Reporting on Health Equity and Health Systems.

Other stories by her include:

Native Hawaiians Face High Rates of Diabetes. That Means More Need for Dialysis

A Coastal Road Connects These Patients To Dialysis. Climate Change Could Make That Harder

Why In-Home Dialysis Is Becoming A More Popular Option In Hawaii

State Rules Make It Harder To Open Dialysis Centers In Hawaii

State Greenlights New Dialysis Center In Kahului

Pacific Islanders Have a Harder Time Getting Kidney Transplants Than Other Patients

The pandemic vastly expanded health care access in this US territory. That may end soon.

Honolulu Civil Beat

AS LITO, Saipan — Abraham Taimanao leans over two pieces of tin and lifts his hammer to flatten them together.

The tin is intended for the roof of a new chicken coop that Taimanao has been building, near rows of hot pepper plants and other plants he’s been cultivating.

This isn’t Taimanao’s land. He’s not exactly sure who owns it. But the 60-year-old comes here every day because it reminds him of his real home — his farm on the island of Rota, nearly a half-hour flight away.

“I come out here just to give me a peace of mind, not thinking about dialysis, not thinking about anything else, but to enjoy life like what I usually do in Rota,” says Taimanao.

Abraham Taimanao hammers two sheets of tin to make a roof for the chicken coop he is building.

Across the street is the concrete building that Taimanao and other dialysis patients have called home ever since they were told that they needed to get dialysis three times a week to survive.

In the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, the only dialysis centers are on the capital island of Saipan. Neighbor island residents from Tinian and Rota, most of them Indigenous Chamorros, move to Saipan to access the life-saving care.

Tinian is home to around 3,000 residents, while Rota’s population is about 1,800. Nearly two dozen of them are living on Saipan solely to get dialysis.

Diabetes, the leading cause of kidney failure, is a huge problem in the U.S. territory, especially among its Pacific Islander communities. One 2016 survey, the latest such survey available, estimated while the diabetes rate was 12.5% among all commonwealth adults, the figure was as high as one in five Chamorro adults and about a third of all adults over the age of 65.

The prevalence of diabetes in the Northern Marianas is driving up the demand for dialysis. In 2018, Saipan’s only hospital, the Commonwealth Healthcare Corp., had just over 100 dialysis patients, but now the number fluctuates between 170 and 180, says Nikki Villagomez, who leads the hospital’s dialysis clinic.

“The increase of patients was steady for a long time. For some reason it kind of skyrocketed out of nowhere,” Villagomez says. “I just see it increasing even more in the future.”

Diabetes is a problem throughout the Pacific and forces people from many islands across the Micronesian region to move to Hawaii and elsewhere in the U.S. to access the necessary care.

In the Northern Marianas, the demand for dialysis on the neighbor islands hasn’t yet been met by supply. Past efforts to open a center on Rota ran up against difficulties recruiting staff.

Congress has appropriated more than $500,000 of rural development funding to help patients conduct in-home dialysis, a growing national trend. But many patients from Tinian and Rota who live on Saipan say they fear infections if they’re performing dialysis by themselves, and what they crave is safe access to a doctor and hemodialysis chairs back home.

In the meantime, many Tinian and Rota residents move to Saipan for care, leaving behind their homes, friends and family members, and the peace and familiarity of those smaller islands.

Dialysis on Saipan keeps patients like Taimanao alive, but at the cost of spending time with loved ones back home. They miss out on birthdays, holidays and traditional ceremonies like the nine-day Chamorro rosaries held to honor deceased relatives and village saints. The longest any dialysis patient can be away from the machines is four days.

Many are following the same path their parents took. Taimanao visited his mother on dialysis in Saipan for 20 years before she was buried back on Rota. He hopes his children and grandchildren don’t end up like him.

‘You Have To Go’

On Rota, Taimanao hunted coconut crabs and deer, went fishing and caught sea crabs to feed his family. When he found out that he would be forced to move to Saipan, he asked his wife, “Where are we going to get the resources to meet our kids’ needs?” Saipan has different rules for fishing than Rota, and Taimanao wasn’t sure where he’d be allowed to hunt coconut crabs.

“We have to go because it’s for your health,” his wife replied. That wasn’t an answer to his question, but she reminded him that staying would mean dying, which would mean saying goodbye to his kids.

“I still want to see my kids,” he told her.

“You have to go,” she concluded.

Similar conversations have played out in many other patients’ homes. Jesus Cruz remembers how his father moved back to Tinian after five years and decided to move back home, even if it meant dying.

Jesus Cruz pays $91 every weekend to fly home to Tinian because he can't stand being far away. Other patients aren't able to afford that.

His father didn’t want to financially burden his family by requiring them to pay for flights to Saipan, a hotel and rental car if he were hospitalized in the intensive care unit.

“It cost money. So my dad said never mind,” Cruz, now 60, said. The family gathered on Tinian by his dad’s bedside when he died in 1998.

Several years later when Cruz was told he needed to get dialysis, he spent four years trying to avoid it because he didn’t want to leave his house and life on Tinian. His kids and grandkids pressured him to go get the treatment.

“I’m doing this for them,” says Cruz, sitting at a picnic table in the courtyard of the apartment complex dedicated to patients like himself. “Not for me.”

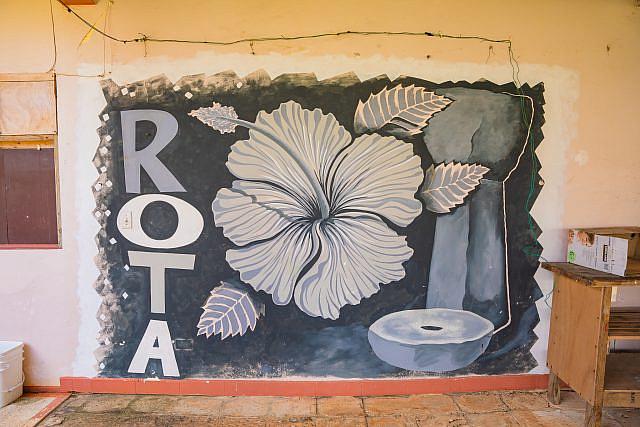

A mural celebrating Rota decorates the interior courtyard of the Rota and Tinian guesthouse in As Lito, Saipan. Many patients must live here in order to get dialysis.

The municipal governments of Tinian and Rota provide studio apartments for patients including Taimanao and Cruz to live in rent-free. They cover the cost of utilities and transportation to and from appointments. Patients get $100 monthly stipends, which helps because their dialysis schedules and health problems make it difficult to work. Currently 13 patients from Tinian and nine from Rota are receiving such services.

The patients are grateful for the help, but it’s not the same as home. On Tinian, Cruz raised 80 pigs on his farm where he also grew bananas, tangerines and lemon trees and had countless chickens. Since he left, the farm turned back into a jungle.

On Saipan, his days are filled with dialysis and chronic pain. He pays $91 for a roundtrip ticket back to Tinian every weekend because he can’t stand being away. He estimates he has spent about $26,000 on plane tickets alone over the past six and a half years. His wife stayed on Tinian and when the pandemic shut down interisland travel, he couldn’t see her for four months.

“I want to feel like I’m home,” he said. “This is not a home for me. I don’t call this home.”

Failed Attempts To Open A Dialysis Center

Sen. Paul Manglona, who represents Rota in the commonwealth Legislature, has been trying to establish a dialysis center for his constituents for more than a decade. In the mid-2000s, lawmakers appropriated $1.5 million to renovate a wing of the Rota Health Center.

The building was complete with a reverse osmosis machine to treat the water and room for at least four dialysis chairs. But Manglona said the space never got up and running because of lack of staff.

It’s still empty and unused. A 2012 analysis found the space would need a lot more renovations before it could be operational.

The dialysis center at the only hospital in the Northern Mariana Islands has 26 chairs.

Manglona wishes that the local hospital could partner with a company to start up a new center.

U.S. Renal Care, a national dialysis company, previously ran five dialysis centers on Guam before selling them all in January 2020 to Fresenius, which operates Liberty dialysis centers and is one of the largest dialysis companies in the U.S.

Pliny Arenas, who leads the Hawaii region for U.S. Renal Care, said that before the sale, the company looked into potentially opening a dialysis center on Rota. But it didn’t proceed because of the challenging logistics of getting supplies from the mainland to Rota.

Scott Sayres, spokesman for Fresenius, said the possibility of opening up dialysis centers in the CNMI is under evaluation.

“We constantly evaluate opportunities to expand our services for patients,” he said. “Many factors go into those evaluations, including what’s best for patients, staffing needs and business requirements.”

Esther Muña is the chief executive officer of the Commonwealth Healthcare Corp., the only hospital in the Northern Mariana Islands.

Staffing needs aren’t a small issue. Esther Muña, executive director of the commonwealth’s hospital, estimates the public dialysis center on Saipan is operating at 80% staffing because of the need for more nurses.

The center has just one nephrologist that it must share with two private dialysis clinics on island. Muña said the cost of hiring another nephrologist could run higher than $300,000 a year. That doesn’t include wraparound services like dietitians and social workers.

She said the facility may become ready, but it’s difficult to pay staff enough to retain them.

“You can provide those services, but then you’re not going to have the stability to continuously provide those services,” she said.

Manglona is frustrated telemedicine can’t provide more options, and is convinced patients who moved to the states for dialysis would return home to Rota if it had a local clinic.

“Why can’t we have the nephrologist here go to Rota every week, every two weeks?” he asks during an interview at a restaurant on Saipan. “We’ll never make it possible if there’s no political will to support it.”

The issue has become more personal to the senator in the last couple of years since his wife was ordered to get on dialysis.

He tried to bring her to Washington state to live with their daughter there to get a kidney transplant, but the closest available dialysis seat was an hour’s drive away, so they moved back to the CNMI.

A Home Away From Home

Some patients who moved to Saipan have found ways to adjust.

“See, I’ve got my onions here, and my hot pepper and this flower the old lady gave me this one, si Auntie Rose,” Harold Manglona says as he points to different pots of plants lined up in the courtyard.

The Rota native is standing outside of his studio apartment on Saipan in the complex where he lives with Cruz and Taimanao.

Harold Manglona, 55, a cousin of the senator, has been on Saipan for dialysis for five years.

Life On Saipan Harold Manglona says Saipan is very different from Rota, where he left behind a farm where he raised pigs, cows, chickens and deer and planted banana trees, tangerine and lemon trees, eggplants, okra, hot pepper and onions.

He initially planned to refuse the treatment, but his siblings persuaded him to do dialysis for his children and grandchildren.

Both his parents were diabetic. Manglona was 49 when he realized he was diabetic too.

He can usually only afford to go to Rota once per year. Tickets are $241 roundtrip per person for locals, or close to $500 if he and his wife travel together.

The 55-year-old retired firefighter decorates the table next to his front door with pictures drawn by his 11-year-old granddaughter. He visits his wife’s relatives on Saipan and goes for walks along the marina or in the big stores that he wouldn’t find on Rota. He dances in the courtyard sometimes to make his fellow patients laugh and temporarily forget their minahalang, the Chamorro word for the feeling of missing something.

“I keep myself busy to forget what I left out in Rota. I’m getting used to Saipan life,” Manglona says as he sits outside his studio apartment. “I got a lot of friends here now.”

Like Taimanao and Cruz, Manglona left behind his farm when he moved. His son sold Manglona’s cows to afford tickets for his family to visit Manglona on Saipan for Christmas.

No Local Transplant Center

For many people with kidney failure, dialysis isn’t the only answer — kidney transplants are another option. They’re harder to get, but every year in the U.S. thousands of patients do.

That doesn’t feel like an option to many patients from Rota and Tinian, who are unfamiliar with the requirements of getting a transplant and concerned about the costs to do so.

“Am I too old for that?” wonders Rose Sylvia San Nicolas, who moved to Saipan from Tinian. She’s 47. “I don’t know. I have to move to the states, that’s another move.”

Rose Sylvia San Nicolas describes how Tinian is different from Saipan as she holds her dog outside her apartment where she has been living on Saipan for over a year. She grows Chamorro medicinal plants such as korason gala on her lanai.

The Transplant Center at The Queen’s Medical Center in Hawaii will sometimes perform transplants on patients even in their 70s, if they’re otherwise healthy. It’s the only transplant center in the Pacific Rim.

Since 2012, the center has performed transplants for 11 patients from Guam, Saipan and American Samoa. Over that time period 20 patients from the Federated States of Micronesia and 11 from the Marshall Islands also got transplants.

The center does not have data on whether any patients from Rota or Tinian have ever received kidney transplants.

Alan Cheung, medical director at Queen’s Transplant Center, said most patients are waiting for a kidney from a deceased donor and the center tells patients to move to Hawaii about six months ahead of when they expect to get a kidney. Most end up staying.

“With the flights available, it is logistically impossible, for instance, for patients from Saipan to fly to Oahu in time for transplant surgery from the time they get the deceased organ offer,” he said. “For this reason, we require patients to relocate to Hawaii when they get towards the top of the waiting list.”

Patients will also need to stay in Hawaii for a year after the transplant for post-transplant care, Cheung added.

Cruz says he’s not willing to move to Hawaii for the slim chance that he could get a new kidney. It was hard enough to move to Saipan. His son even offered to donate his kidney, but Cruz said no because he is afraid his son’s other kidney might fail and that his son could end up on dialysis like his father, uncle and grandfather.

Even if insurance covered most of the transplant itself, moving to Hawaii would be expensive and require covering the high cost of rent and food in the state. Manglona has thought about trying to get a transplant but says he’d rather save his money to give to his kids and grandkids.

The commonwealth’s medical referral program — which helps many patients access health care in the states — doesn’t support patients moving for transplants because getting one requires such a long wait, said Villagomez, the Saipan dialysis center director.

Another Option: At-Home Dialysis

Muña thinks the answer for patients living in Tinian and Rota lies in at-home dialysis.

Peritoneal dialysis is a form of at-home dialysis that patients can do themselves by sticking a tube in their abdomen that filters blood. At home hemodialysis, which is an option in Hawaii, is not an option on Rota or Tinian, Villagomez said.

Congressman Gregorio “Kilili” Sablan asked for $391,500 for peritoneal dialysis on Rota in the 2022 budget and another $389,250 for Tinian this year.

Congressman Gregorio Kilili Sablan asked for money for in-home dialysis.

He said he put in the request at the urging of Muña, the hospital executive director. The hospital has about a dozen peritoneal dialysis patients, up from previous years, but is hoping to expand the program.

But first the hospital will have to overcome patients’ fears. Many of those staying on Saipan know people who got sick with infections after trying out peritoneal dialysis and those stories have discouraged them from trying themselves. Part of their concern is the lack of a real hospital on Tinian or Rota — an infection could require getting an emergency evacuation to the hospital on Saipan.

Plus, not everyone is qualified for peritoneal dialysis. Doctors have to certify that patients are not only physically capable of it but have enough space in their homes to do so.

Ambrocio Ayuyu, 62, quit his job and moved to Saipan three years ago to take care of his wife Rose, 66, who needed dialysis. His wife is not only sick with kidney failure but also uses a wheelchair after having a foot amputated.

Ayuyu says he and Rose considered peritoneal dialysis, but they can’t afford to pay for air conditioning at their house on Tinian, where they rely on fans to counteract the tropical heat. Ayuyu says he was told air conditioning is necessary to keep the dialysis supplies at a certain temperature.

The Most Quiet Place Ambrocio Ayuyu, who moved with his wife to access dialysis on Saipan, describes life back home on Tinian compared to Saipan.

He’s only been able to afford to go back to Tinian once since moving to Saipan three years ago.

Leaving Tinian meant leaving most of his children and grandchildren, and hundreds of chickens and ducks on his farm. Instead of working on his farm, his daily routine in Saipan now involves doing laundry and cleaning the apartment while his wife gets her treatment.

“Most of the day, nothing to do, so we just stay home and sleep,” he said. Since he moved to Saipan, he’s gained 20 pounds and his cholesterol levels have worsened.

San Nicolas, the Tinian patient, hadn’t been planning to move at all when she was medically evacuated from Tinian to Saipan on January 6, 2021. There was no opportunity for a second opinion or any time to think about it.

Missing Her Family Rose Sylvia San Nicolas compares her life on Saipan to life in Tinian. She can't wait to move back home.

She was so depressed in the first months of the move that she lost 70 pounds. She tried to do home dialysis but was told that she’d have to give up her dog, a beloved Maltese named Sugar Boy that she calls her son, in order to do it.

But after a year and seven months of having to live away from her siblings and only child, she has decided to ask her husband to build a dog house for Sugar Boy outside their home in Tinian so that she can qualify for peritoneal dialysis.

Her days on Saipan are filled with work and treatment and none of the joys of family gatherings that she had on Tinian. On Monday, Wednesday and Friday, she works at a human resources job at the hospital from 6:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. before going to dialysis, where she sometimes stays as late as 8:30 p.m. Tuesdays and Thursdays she can start work later but is often tired from the previous days.

Growing plants and spending time with her dog and husband helps with the homesickness, but it’s not enough. She misses Tinian’s clear waters — swimming in Saipan’s shallow lagoons isn’t the same. But mostly she wants to be near her daughter and her siblings.

“My priority is I want to be reunited with my family,” she said. “If you’re with your family, even if you’re down, you’re always up.”

Praying To Go Home

Even though Harold Manglona is doing his best to adjust to Saipan, he wishes he could get the treatment he needs in Rota.

“We’re losing out by staying here on Saipan,” Manglona said. “We should be somewhere where we can do something for our family and for ourselves.”

Once he joked to his neighbor Cruz, “The only time we’re going to stay in Tinian or Rota is in the coffin.”

It’s not really a joke. Manglona has already seen six other patients from Tinian and Rota die — he points to the apartments they lived in: one, three, eight. He already has his burial plot picked out on Rota. It’s where he wants to be buried even if he can’t live there anymore.

Taimanao also jokes darkly about finally going home as cargo after he dies. He misses hunting coconut crabs on Rota, and is wary of trying it on Saipan where he doesn’t know who owns which land.

Cruz wishes the government and a private company could work together and find an alternative to help patients like himself — and not just himself, but the patients who come after him.

“Are they going to go through what we’ve been through?” he wonders.

This story was produced with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 Impact Fund for Reporting on Health Equity and Health Systems, and Civil Beat supporter Dr. Mary Therese Perez Hattori.

[This article was originally published by Honolulu Civil Beat.]