Before Medicaid, how did doctors treat the poor?

In the era before modern surgery and antibiotics, care for all but the very elite was provided by unschooled healers such as midwives, "bone-setters," and apothecaries. Their fees were low, and many would barter their services for crops or food.

Kathleen O'Brien reported this story as a project for the National Health Journalism Fellowship, a program of the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School of Journalism. This article was originally published by NJ.com. Other stories in this series can be found here:

N. J. Medicaid fiasco: Thousands stranded without coverage, no fix in sight

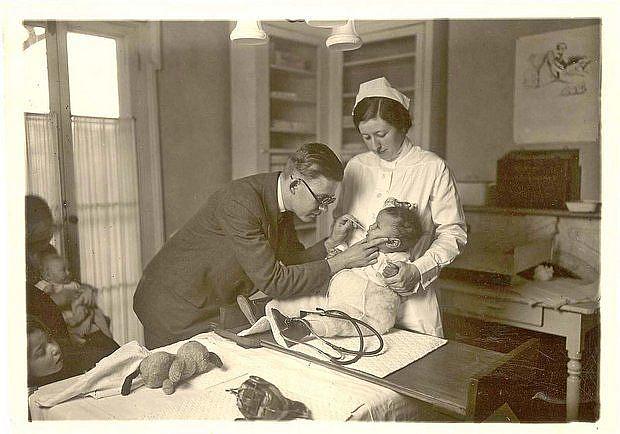

In an era before government and private insurance, local doctors routinely charged their wealthy patients more and their poor patients less. This informal sliding scale allowed them to offer charity care. (Millburn-Short Hills Historical)

While Medicaid is the primary way to cover the poor, charity care used to be a far simpler proposition for doctors, said David S. Jones, the A. Bernard Ackerman professor of the culture of medicine at Harvard University.

In the era before modern surgery and antibiotics, care for all but the very elite was provided by unschooled healers such as midwives, "bone-setters," and apothecaries. Their fees were low, and many would barter their services for crops or food.

"The families would give what they could. Sometimes it was a chicken, sometimes it was a roll of cloth. Sometimes they would show up months later, when their fortunes had changed, and say, 'Here's a turkey. Thanks for taking care of us,' " Jones said.

On the eve of the American Revolution, there were only about 200 doctors who had actual medical degrees. Even as late as 1820, he said, there were only three hospitals in the whole country. The trustees of early hospitals had control over who would be admitted, and would routinely turn down patients they perceived as drunkards, prostitutes, or the contagious.

"It was a totally funny system, and they would give this kind of assistance only to those they considered the 'worthy' poor," Jones said. Doctors often donated their services.

Underpinning all these arrangements was the notion that doctors have an obligation to provide charity care. Not only does society expect it, doctors expect it of themselves as well. The American Medical Association even has a "Caring for the Poor" section in its code of ethics, admonishing members "to share in providing care to the indigent."

In the early 1900s, before health insurance became widespread, a small-town doctor was free to devise his own "sliding scale" fee structure, Jones said. He would charge the factory owner one price, the factory worker a lower price.

The factory owner's high payment would subsidize the factory worker's care. Everybody knew what was going on, Jones said, and saw the arrangement as sensible and just.

The arrangement worked until after World War II, when government and private insurance companies became more involved in paying for care. Now a doctor could no longer charge a wealthy patient more than a struggling one, for insurers and public programs wouldn't allow it.

Further threatening the math behind an informal sliding scale was the subsequent move by insurance companies to rein in doctor fees. Using their bargaining power, they got major price concessions from doctors in exchange for sending patients their way.

The net effect, however, was the disappearance of the old financial cushion provided by the factory owner's payment.

"Barter economies, sliding scales ... the minute insurance came into the picture, that stuff disappeared," Jones said.

Now we have a government-funded system built on two morally questionable assumptions, said Princeton University health economist Uwe Reinhardt, who served three terms on the national commission that advises Congress about physician pay rates.

Suppose he teaches three undergrads at Princeton, he says. One goes to law school and becomes a lawyer, one gets an MBA and goes to work on Wall Street, while the third goes to medical school and becomes a doctor. Of the three, he says, only the doctor is expected to provide free or discounted services.

"I love the way, with one wave of your hands, you somehow tax the doctors and nurses and make them give charity care," he said. "I view giving charity care when it's expected of you as a tax."

The second bit of uniquely American illogic embedded in the Medicaid system is the assumption that a doctor's services are worth less when administered to a poor person, he said.

Put another way, rates are based on the social status of the patient. "If a doctor worked an hour with a patient, he should get paid," Reinhardt said. "And yet we say, 'No, you should be paid less because you treated a poor person.' What kind of orange juice did we drink in high school? It's an outrageous idea."

The United States falls somewhere between countries that see health care as a right that government should provide, and countries that are comfortable having health care only for those who can afford it, he said.

We don't want people dying without care, or giving birth on the sidewalk, he said. Yet we don't want government to pay for everyone's care.

We split the difference by having an underfunded program like Medicaid, an "institution that allows us to fake it," he said.