The pandemic shines a light on just how many school-related infractions end with children in the juvenile justice system

This story is part of a project for the 2021 Data Fellowship with the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

Other stories in this series include:

Reading through the lines: The correlation between literacy and incarceration

When COVID closed schools, fewer kids entered jail.

Graphic credit: Zoe Hambley

As a former district court judge, state Rep. Marcia Morey has seen firsthand how children can get entangled in the state’s juvenile justice system.

The path from school to the courtroom is similar for many kids, Morey said. They skip school, break the rules or act out in class, prompting a visit from the school resource officer. However, Morey says these are often children with learning disabilities or who come from “dire” home situations.

They need help, not punishment. But their cries for help too often become crimes.

Morey, a Durham County Democrat, has led legislative reforms to the juvenile justice system aimed at decreasing the number of referrals from schools that funnel kids into that system.

The number of school-based delinquency complaints coming from schools has decreased over the past decade, but the percentage has stayed roughly the same — hovering around almost half of overall complaints, regardless of reforms.

The one thing to disrupt that trend? A nationwide public health crisis.

“Because our clients haven’t been in school, they couldn’t get suspended. They couldn’t get referred,” said Virginia Fogg, supervising attorney at Disability Rights North Carolina, who advocates for children with disabilities who get caught up in the juvenile justice system.

When the country shut down in March 2020 because of the newly-emerged coronavirus, schools were forced to go online for the rest of that school year. Schools across the state did not go back to fully in-person learning until close to the end of the 2020-2021 school year, when Gov. Roy Cooper signed a bill in March 2021 agreeing to allow schools to resume in-person learning.

With kids learning at home, school-based juvenile justice complaints fell to about 30 percent of total complaints during the 2019-2020 school year, according to data from the North Carolina Judicial Branch.

During the 2020-2021 school year, as the pandemic continued to keep kids out of school, school-based complaints sank to just 7 percent of overall complaints.

“We saw students escaping the justice system because they weren't in school,” said Marcus Pollard, Justice Systems Reform Council for the Southern Coalition for Social Justice. “The pandemic really showed us that students are being really transferred from the school system to the justice system.”

The COVID-19 pandemic showed that it is possible to change the prevailing trend, but that also means interrogating what exactly about the school environment can be toxic for some youths.

What happened during the pandemic?

North Carolina’s juvenile justice system anticipated large increases in referrals to the system in 2020 because of the implementation of the Raise the Age law in December 2019. The legislation made it so 16 and 17-year-olds who committed nonviolent crimes would no longer be processed through the adult criminal justice system. North Carolina was the last state in the country to pass the bill, which sent kids through the juvenile justice system instead of adult court.

But the pandemic changed everything. From July 2019 to the end of June 2020, more than 70 percent of North Carolina’s counties saw a decrease in school-based complaints, compared with the preceding four years despite implementation of Raise the Age, data analysis of North Carolina Judicial Branch data by NC Health News found.

“We're glad the numbers are down,” Fogg said. “But we're not jumping up and down.”

Exposing the school-to-prison pipeline

Despite decreases in confinement of kids under the age of 18 over the past 20 years, more than 48,000 youths in the United States are locked up on any given day, according to a 2019 report from the Prison Policy Initiative.

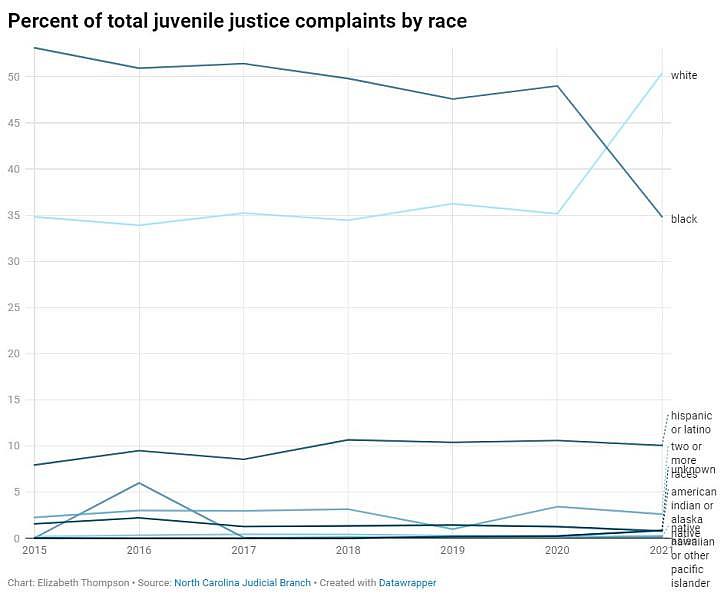

The juvenile justice system disproportionately marginalizes youths who are Black, economically disadvantaged or have disabilities, statistics show. Criminal complaints in North Carolina are filed against Black youths more than any other race. Though Black kids make up 20 percent of the children population in the state, they received almost half of total complaints in 2019, according to data from the North Carolina Judicial Branch.

Advocates against youth involvement in the juvenile justice system say Black and brown students are unfairly targeted by School Resource Officers (SROs), those law enforcement officers who work in school settings.

“If a white student’s in school, and they're referred to the principal's office, it's not being ended with handcuffs,” Pollard said.

Students with learning disabilities or behavioral health issues may also unwittingly commit a crime while acting out of frustration. If a SRO is there when it happens, those crimes get elevated to the juvenile justice system, Fogg said.

“What is the role of law enforcement on school grounds?” Morey asked.

Should it be to keep schools safe from outside threats, Morey said, or to police student disciplinary matters on the inside?

The current system takes some of the decisions about criminality out of the hands of school administrators. Right now, SROs can refer a child to the juvenile justice system without the input of school administration, Morey said.

Not every child who is referred to the juvenile justice system is incarcerated — in fact most of them aren’t. Out of thousands of complaints, juvenile detention admissions did not exceed 270 in any given month in 2020, according to data from the North Carolina Department of Public Safety.

Nonetheless, simply being referred to the juvenile justice system can still be harmful, Morey said.

“Once you enter the system, you're a delinquent or you're known to be ‘in juvie’ or ‘in court,’” Morey said. “And I think we often overlook the traumatic experience of labeling them. Oftentimes, it starts a trajectory of ‘Oh, I'm bad, and this is now the path I'm going.’”

A report by the North Carolina Poverty Research Fund found that North Carolina’s juvenile justice system is used as a safety net of sorts for children experiencing behavioral health issues or poverty. Teachers or other school staff may refer a child into the juvenile justice system with the intention of getting them help, such as access to mental health resources, said Heather Hunt, a research associate at UNC School of Law.

That does not erase the fact that the juvenile justice system is, at its heart, a carceral system, not a service system. In order for children to enter the system, they must be accused of a crime.

School-based crimes

The crimes that youths commit in school to get funneled into the juvenile justice system tend to be less serious than complaints that come from outside of school.

“By and large, if you look at the offenses, they are minor,” said Eric Zogry, state juvenile defender at the North Carolina Office of the Juvenile Defender. “[They’re] behaviors from adolescence, which is getting into minor fights, or getting upset in class and then being charged with disrupting school.”

The top 10 school-based offenses in 2019 were all misdemeanor or status offenses, with simple assault, disorderly conduct at school and “simple affray” — getting into a fight — making up the three most common complaints, according to a report from the North Carolina Department of Public Safety.

“These terms are also a little broad,” said Aelya Salman, communications advocate for the Southern Coalition for Social Justice. “Simple assault can be used quite freely depending on who is filing the complaint.”

Fogg from Disability Rights North Carolina said some of the most common complaints children with disabilities come to her with are crimes like making threats against the school or school officials.

“It's a cry for help,” Fogg said, “making some completely outlandish statement that they know is going to get the attention of the adults in their world, because that's how high their anxiety has gotten.”

For many students with disabilities, school is a place where they can be frustrated and humiliated. It’s a place they dread going to, Fogg said. If they know they can be suspended by acting out, they might do so on purpose.

“They're trying to get out of that school environment, which is one of the reasons that we argue against suspension,” Fogg said. “It's actually encouraging that behavior, even though that may not be immediately obvious.”

Back to school

The decrease in school-based complaints to the juvenile justice system for Black youths showed that those children have an “increased possibility of being arrested just by means of going to school,” Pollard said.

But keeping kids away from classrooms where they’re likely to be profiled has its own drawbacks.

Advocates for children argue that suspending children from school, as well as other actions that keep them out of the learning environment, are also a problem because it puts them further behind and makes it more likely for them to get in trouble outside of school.

About 30 North Carolina counties showed an increase in non-school-based juvenile complaints in 2020 compared with the average over the previous four years.

The 2020 blip showed that it is possible for school-based complaints to plunge and to prevent children from falling through the cracks and into the juvenile justice system.

“What was going on with these kids?” Zogry asked. “The answer is not much. So, I would hope that people are rethinking how to deal with minor disciplinary behavior. But it's way overdue.”

2020 was an exception, but advocates doubt juvenile justice complaints will remain this low. The same factors that made school toxic for marginalized students before the pandemic were still there when children returned to in-person school starting in the spring of 2021. Whether numbers began the rise again once kids returned to school will only be known once those numbers are released.

The “When kids’ cries for help become crimes” series is part of a data fellowship with the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

[This article was originally published by North Carolina Health News.]