Part 3: In California, a data-driven 'life boat' for those transitioning out of foster care

"Fixing our foster care crisis” was made possible through major funding from the Community Foundation for Southern Arizona and additional support from the University of Southern California Annenberg Center's Fund for Journalism on Child Well-being.

Other stories in Part 3 of this series include:

Hard work of reunification often entails rehab, intensive home services

How states can help children return to repaired families

Out of the system, young adults find themselves 'flooded with freedom'

In their own words: Aracely Valencia

In their own words: Donald Jayne

In their own words: Alexei Ruiz

“I felt unwanted:” Tucson kids talk about hardships of foster care

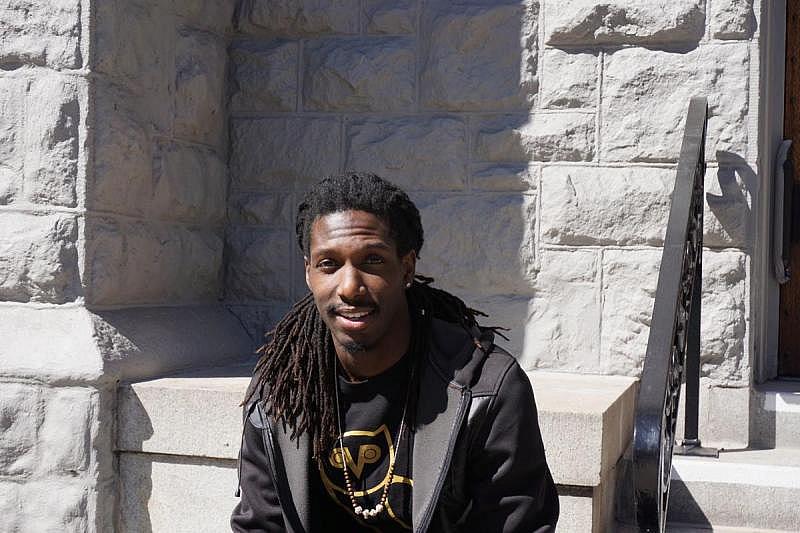

First Place for Youth, a nonprofit organization based in Oakland, California, helped Will Smith, 23, get his own apartment. Most clients are in the program for about two years. Courtesy of First Place For Youth

By Sarah Garrecht Gassen Arizona Daily Star

Success is not measured in hugs.

This a core tenet of First Place for Youth, a nonprofit organization that runs a housing, education and job development program in California from its home office in downtown Oakland. It operates in six counties, including San Francisco, Los Angeles and Santa Clara.

First Place was founded 20 years ago by UC-Berkeley graduate students Amy Lemley and Deanne Pearn. They noticed that young people who aged out of foster care at 18 ended up homeless, unemployed and often in crisis. They were adults on paper, but didn’t have the life skills, education, work experience or stable housing needed to make it on their own.

Helping the youths with the least social support, fewest skills and steepest hill to climb to bridge this gap is First Place’s mission. And, thanks to the copious measurements they collect and how they use that information, it works.

“Everyone gets a risk factor score,” said then-CEO Sam Cobbs, in his Oakland office, last summer. “What makes us different is the higher the risk factor score, the higher a priority they are to get in the program. We’re going to take the Titanic approach and say, ‘Get into the life boat.’ “

Early in his career, Cobbs was working in San Francisco with a shelter for homeless youths ages 18 to 24. One number stunned him:

Of the 400 young people who’d used the shelter his first year there, 370 had been in foster care.

It became clear that if he wanted to help homeless youths, he “needed to work on the pipeline first.”

That led him to foster care services. He’s worked at First Place for Youth for more than 12 years, and left in mid-February to join Tipping Point, a nonprofit that fights poverty in the Bay Area.

Fidelity to the system and the data, and an understanding of their clients, are essential to First Place’s success. “You can’t give up on them,” Cobbs said. “These are 18- and 19-year-olds. They don’t always follow logical trains of thought. You have to be able to stick with them.”

In California, like Arizona, a young person can volunteer to stay in the child welfare system until age 21. First Place serves clients from 18 to 24; most are in the program for about two years.

Unlike some other programs, including in Arizona, a young person can come in, leave, and decide later to come back.

“That first great breath of freedom. It was exciting — until I got on my own,” said Carmen, who started in First Place at 17 but wasn’t ready for it. She left for a year and then reached out to come back. “I was more clear that time what I needed to do and what steps I needed to take. I was grateful for that second chance.”

Carmen, who did not want her last name used to preserve her privacy, graduated from First Place at 24.

First Place’s name describes its core: help youths transition from foster care to a place of their own, typically an apartment with a roommate. The lease is signed with the nonprofit, not the youth, so landlords are willing to accept the young tenants. More than 1,000 current and former foster kids have been housed through First Place over the past decade.

Market-rate for a two-bedroom apartment in Oakland is $2,100 a month; in San Francisco, it’s $3,000-plus.

The youths pay a significantly discounted monthly rent, and the rent money they pay goes into a fund they receive when they complete the programs.

Each youth is assigned a youth life advocate, and an employment and education advocate. They work together, each staff member focusing on a piece of the whole youth. They each keep detailed records, and are responsible for knowing what is going on with the youth in all areas. Again, the information provides the connective tissue that keeps the mission together.

For First Place, everything boils down to an essential question: How do we know what we are doing works?

As board member Andy Monarch puts it, First Place for Youth has the “courage to look at the data” and change.

PROGRAM’S EVOLUTION

About a decade ago, Cobbs realized First Place was losing staffers with alarming frequency. It’s a tough job, and burnout happens. But this, he thought, was something more.

He asked a powerful question: Why are we hiring the people we’re hiring?

He dug into the fine-grain details and found an answer: First Place had been hiring for skills, not culture.

As the organization shifted toward tracking measurements, about 70 percent of the employees left, Cobbs said. The change needed to happen, he said.

Skills can be learned, but if you don’t accept the information-gathering- and performance-driven culture, First Place won’t be a good fit. And that’s OK, Cobbs said.

“We hire a certain personality type,” he said. “You need to be competitive, numbers-driven and want to be better.”

First Place has data built into its DNA, Cobbs says.

Everything is measured.

Caseworkers track measurements — how many visits or interactions with each person on their caseload, how the client is doing with his or her goals. The information is available to everyone involved. Financial details about the program are available to everyone, too, including the youths.

A detailed tracking system allows them to chart not only their clients’ progress, but the performance of every employee. Goals are mandatory and measuring is essential. Raises are tied to them — not the cost of living — as is continued employment.

First Place staffers are evaluated on youth outcomes, such as: Has the youth avoided pregnancy or the justice system? Do they have a paying job?

“It’s getting to a place where we can get data in real time to people working with youth,” said Charlie Leer, a senior reporting analyst for First Place. “The numbers tell you the ‘what’ but the qualitative piece tells you the ‘why.’”

The information serves double duty: It tells the staff working with a specific person what has been done, what’s working, what’s not, what needs to be done.

And it helps build a picture of how to help youths on a broader scale. It’s a predictor of sorts.

For example, Cobbs said their analysis found that 85 percent of their youth clients who receive a high school diploma or GED while with First Place started the program with an 8th-grade reading level and 5th-grade math level.

That revealed a challenge, he said, but the data also showed that 90 percent of youths coming into First Place enter with a seventh-grade reading level and third-grade math level.

So, they know it is essential to help a student increase their reading and math comprehension early on if they’re going to have a chance at a diploma or GED.

“We measure everything we can, but there are things we can’t measure,” Cobbs said.

TRACKING ISN’T EVERYTHING

Success can’t be measured in hugs, but failure can be measured in anonymity and isolation. “Data alone will not change lives,” Cobbs said.

For all its emphasis on tracking and evaluation, First Place works because everyone understands that measurement is different than story.

Your story belongs to you. It’s not the sum of you, and it’s not your future.

Youths who have been in the foster care system are very aware that dollars are attached to them. Their pain and life circumstances have been, in effect, commodified.

Mistrust is a natural byproduct — are you helping me because you care about me as a person, or because you’re paid to pretend you care?

For a person who has lived within the foster care system, that sense of self takes on deeper importance, said a group of program graduates gathered for a discussion at First Place.

Around a conference table, and over a lunch of chicken, beans and rice, they spoke about ownership, belonging, independence, consequences and responsibility.

“When you’re in the system, you don’t have a choice to what you say, what people know about you,” said Carmen, now 27.

Every person involved understands, from some perspective, foster care. “When someone tells you their stories, they don’t just want to hear yours,” Carmen said.

The connection begins when a youth walks in the front door and talks with an intake specialist, said Kathie Jacobson, the chief operating officer.

“We’re hearing their story in their own words,” she said. “We’re getting their life story, which is also the beginning of building a relationship.”

Housing is the first step, she said. First Place has about 300 available beds in California, with 135 of those in Oakland.

After living in a group home or a foster family, being on their own, even with a roommate, “can bring them face to face with what they don’t have,” she said.

Once housing is settled, the youths are evaluated for educational and employment needs and matched with First Place staffers.

Will, 23, was about to graduate from First Place For Youth in mid-June. He met with his First Place youth advocate, Kate Rose, on a Tuesday morning at his apartment, which was almost empty. His roommate had already moved out, and he was in the process of moving his belongings into a dorm at San Francisco State. Courtesy First Place For Youth

The young adults First Place serves need help evolving from surviving to thriving. The foster care system demands immediate, day-to-day survival skills. Staying quiet, or calm, not making a fuss or asking questions or being seen to be causing problems is a survival skill.

When your life has taught you everything can change on a moment’s notice and you have no control over what happens to you — where you sleep that night, the school you attend — the need for safety is overwhelming, and elusive.

Building trust between the youths and First Place is essential — and difficult, because in foster care the stakes are so high. Mess up in one living situation, and you’ll be moved to another. And another. And another.

“It can be six months before they believe that we’re not going to take the apartment away for no reason,” Jacobson said. “The kids come from places with many rules and regulations. They don’t know how to have their own day.”

Jerah, 20, said she was nervous the first night in her apartment. “In foster care I lived with seven girls. I’d never been in a house alone.”

When Carmen first moved in to her apartment, she was excited, but scared. She kept the oven light on at night.

“It was surreal,” she said. “It was nice to have friends over — and tell them when to leave.”

LIFE IN A DORM

In mid-June Will Smith is about to graduate from First Place For Youth. He meets with his First Place youth advocate, Kate Rose, on a Tuesday morning at his apartment, which is almost empty. His roommate has already moved out, and he is in the process of moving his belongings into a dorm at San Francisco State.

He came to First Place after an instructor at Merritt Community College gained Will’s confidence enough that he finally shared his secret: After classes each day, he went to live in his car or a homeless shelter.

Will entered foster care when he was about 4 years old. He’d been living with his grandparents. One day they took him to a police station, and told him to wait on a bench.

He sat there for about three hours before anyone noticed and asked where his family was. In the bathroom, he said.

Will was taken into foster care and placed in a home where he said he was starved and abused. He dropped out of school in the 10th grade.

Now age 23, after two years at First Place, he has his associate’s degree and is moving into the dorm at San Francisco State. He’ll be studying communications. His youth advocate, Kate, asks if he knows anyone who has lived in a dorm. He doesn’t. No one in his family and immediate circle has graduated from high school.

Visiting Will at his apartment in June, it’s clear he’s been struggling some with the idea that his time at First Place, with the security and safety of a youth advocate, is ending.

Will likes to know what the plan is, what to expect, what’s going to happen — a byproduct of growing up without any control over his life.

He’s a young man who thinks through not only Plan A, but Plan B and Plan C. He wants to be ready for what’s next — and living with uncertainty is a struggle. It’s not an unusual frame of mind for someone who has survived what Will has. When Kate asks if he has any possessions he wants to be sure to take with him to the dorm, he shakes his head, and points to his long braids. “My hair — that’s the only thing I’ve had with me the whole time.”

He’s looking forward to college and living in the dorm, free for the first year under a California program called Guardian Scholars, but it boils down to a raw fact: “It’s really all I have. It’s what I have to do. I didn’t have anything to fall back on.”

“I hate change but I don’t shy away from it,” he says.

“The feeling of change is sickening,” Will says. “We build relationships and then we have to part ways.”

Kate nods silently, watching him and taking in what is said and what’s left unsaid.

He looks down, at his hands in his lap, and then back up.

“I’ve been through worse.”

[This story was originally published by the Arizona Daily Star.]