Asian Immigrant Women Who Decide to Have Children Later in Life Find that Immigration and Infertility May Stand in their Way

The story was co-published with World Journal as part of the 2025 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.

Photo by Sina Schuldt/picture alliance via Getty Images

Starting over in a new country takes time — and for women, the window for having children is limited. Some immigrant women wait to try for children until they’ve found stability. But by the time they’re ready, age and infertility may already stand in the way.

“We came to the U.S. with nothing. We had to work hard, build from scratch. I couldn’t imagine having a baby while waiting tables,” said Marina Tse, who came from Taiwan to the U.S. at 21 in the 1970s and regrets missing her chance to be a mother.

As an immigrant woman living in the country on her own, Tse worked tirelessly to succeed. In her 20s, she juggled jobs and school. By her 30s, her American dream was beginning to take shape. Her 40s were the busiest years—working over 10 hours a day, traveling a lot, and sometimes even sleeping in airports. “With a life that intense, how could I possibly get pregnant?” she recalled.

For many Asian immigrant women, a combination of career opportunities, immigration anxieties, and the loss of nearby family support is reshaping how and when they choose to pursue childbirth— sometimes with irreversible consequences.

Tse spent her career in education, starting as a teacher and later as an advocate for equity in schools. She went on to serve on the California State Board of Education and then in the U.S. Department of Education.

“Having children takes support. As an immigrant, I had to build that sense of security for myself,” she said. “Unlike American-born families, who may have more family and social resources to rely on, I was completely on my own.”

As the years passed, so did the opportunity to have kids. The demands of work and the absence of strong support kept delaying her plans. “Before I realized it, it was too late,” Tse said.

Tse’s experience is echoed in broader demographic trends that reveal a significant decline in fertility rates among immigrant women in the U.S., especially those from Asia.

What the Data Shows

There is a general notion that immigrants boost the U.S. fertility rate. But the trends are shifting.

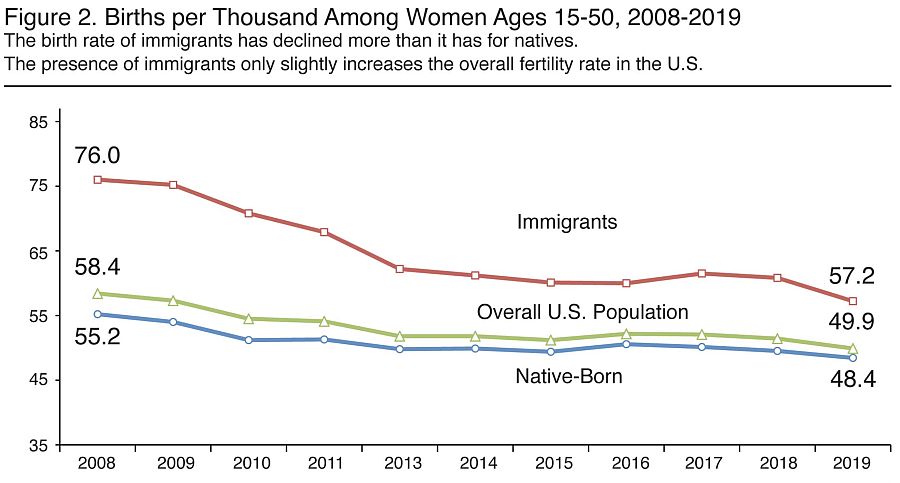

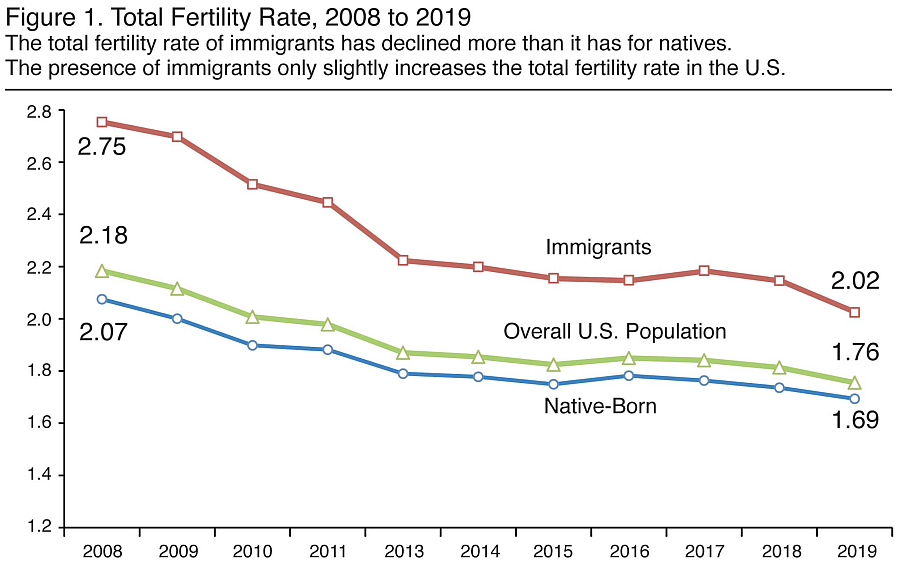

The gap between immigrant and native-born fertility has narrowed. Census data shows that the birth rate for immigrants ages 15 to 50 declined from 76 to 57.2 births per 1,000 women between 2008 and 2019 — a drop about twice as large as that for native-born women.

Among all ethnic and racial groups, Asian and Pacific Islanders have the lowest birth rates.

The average number of children born to immigrant women also has declined more sharply. In 2008, immigrant women averaged a total fertility rate(TFR) – A calculation of the average number of children a group of women would have at the end of their reproductive period – of 2.75 children; by 2019, that dropped to about 2, twice the decline seen among native-born women, which declined from 2.07 to 1.69 – according to census data.

Foreign-born Asian women experienced faster fertility declines than native-born Asian women.

So what’s driving these trends?

Fertility and visa backlogs

According to the World Health Organization, women’s fertility rates decline noticeably after age 35. And age is one of the key factors associated with infertility.

For immigrant women, the lengthy and uncertain visa process often overlaps with their prime reproductive years, and can delay their decisions to have children.

The U.S. immigration system is complex and widely known for long wait times. Its per-country caps and numerical limits on visa categories have led to significant backlogs, particularly for high-demand countries such as China, India, and the Philippines. Some family-based categories can have wait times that can stretch beyond 20 years.

Recent rhetoric and policy proposals around visa restrictions and travel bans under the current administration could further tighten these caps or restrict visa access, potentially worsening the delays and adding pressure for immigrant women considering childbearing.

“We will also revise visa criteria to enhance scrutiny of all future visa applications from the People’s Republic of China and Hong Kong,” stated the U.S. Department of State on May 28, 2025.

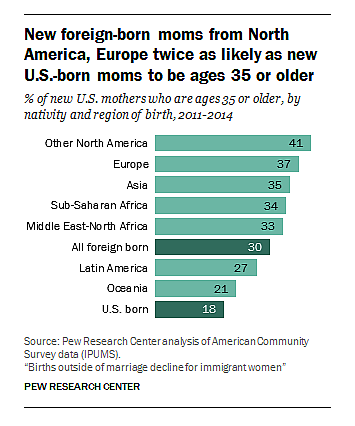

Since 1970, shortly after the Hart-Celler Act introduced per-country caps on visa categories, foreign-born new mothers have consistently been older than their U.S.-born peers. New mothers from Asian countries are more likely to be 35 or older – twice as likely as U.S.-born mothers. Chinese mothers exceed even that average.

Ripple effects

Immigration-related uncertainty also creates ripple effects. Years of waiting can lead to issues like family separation, making prospective parents hesitant to raise children.Many families want their kids to grow up in a stable, unified household.

The Trump administration’s intensified deportation efforts amplified fears. Aggressive immigration enforcement — through raids, detentions, and policy rollbacks — can lead to families postponing their decision to have kids.

Studies have shown that when immigration enforcement became stricter, fewer undocumented women chose to have children. More challenging enforcement environments can reduce household income, limit access to health care, and increase overall anxiety about the future. These pressures may lead families to postpone or forego having more children.

In times of uncertainty and limited resources, childbearing becomes a risky and often unaffordable decision.

“Minority women often experience higher levels of stress,” said Dr. Ping Xia, an embryologist and a researcher at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. She emphasizes that emotional burdens don't just affect decision-making but also disrupt hormonal balance and reproductive function.

“Reproductive potential varies from person to person, but chronic stress, poor sleep, and unmanaged anxiety can reduce antioxidant levels and accelerate ovarian aging,” she explained. “That kind of long-term strain has real consequences on egg development.”

Dr. Ping Xia in her lab. Courtesy Ping Xia

The cultural weight

In many Asian cultures, women are traditionally expected to serve as primary caregivers— a role that often implies significant sacrifices in time, finances, and career growth. As a result, the idea of having children can feel especially overwhelming, particularly for those without strong support systems.

Foreign-born new mothers are much more likely than their U.S.-born mothers to be unemployed, with half reporting being out of the workforce.

Meanwhile with the loss of traditional support systems like having one’s family nearby or strong community ties, immigrant women may feel greater burdens when making fertility decisions.

“We often hear about the pain of childbearing but rarely talk about the joy,” Dr. Xia said.. “Those conversations can make fertility feel like a burden rather than a possibility.”

In addition, traditional family values and cultural expectations surrounding motherhood – the pressure for women to have children can also deepen the regrets when opportunities are missed.

Disappointments from parents longing for grandchildren, feeling left out at family gatherings, and casual questions from friends can all serve as painful reminders. In a community where having children is widely seen as essential to a complete family, the emotional toll of not becoming a parent can feel even heavier.

“In Chinese culture, family is the foundation of everything, and children are a mother’s closest bond within the family,” said Tse, the educator who regrets not having children as she worked to establish her career..

“Sometimes I feel depressed thinking about it. It’s a regret I carry,” she said. “As I’ve grown older, that feeling has only deepened.”

Despite her career achievements — including her appointment as assistant deputy secretary at the U.S. Department of Education — Tse says she would have traded her career success for the chance to be a mother.

“I’m not saying everyone has to have children, and of course, they aren’t everything in life,” she said. “But here’s my heartfelt reminder: Career opportunities will always come — but fertility doesn’t wait.”

“It’s possible to have both. But it takes planning and thinking ahead.”

Planning matters

Reproductive technologies such as egg and embryo freezing and in vitro fertilization (IVF), which improve the chances of pregnancy, may give women more control over their fertility timelines.

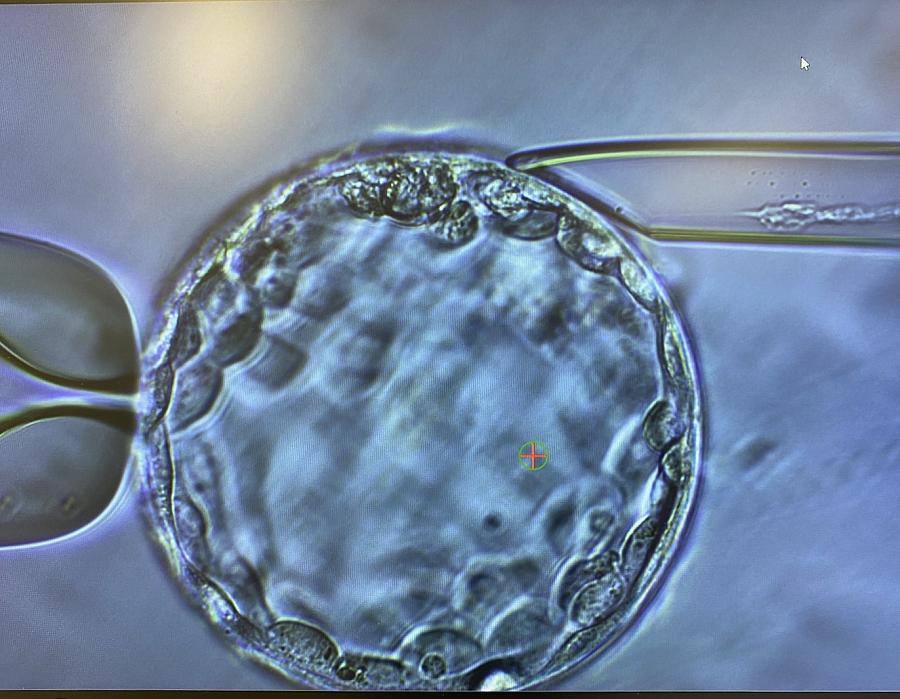

Blastocyst Biopsy. Courtesy Ping Xia

"It's like buying an option — you may never use it, but it gives you a window of possibility,” said Minyi Zhang, director of Ember Fertility Center in Orange County, California, a region with a large Asian population.

Still, she cautioned that even the most advanced technologies are no guarantee. “Most women come to us in their 40s — by then, they’ve often missed the optimal window,” Zhang said, adding that age 35 is a critical threshold for these treatments, yet fertility is rarely top of mind for younger women.

In Zhang’s experience, some couples struggle in silence for years before seeking help. Others wrestle with the emotional weight of deciding whether to have children — and, in the process, lose precious time. “The best years just slip by,” Zhang said.

“You can sense the cultural stigma at play,” Zhang said. “In some cases, it’s the woman’s family — not the woman herself — who reaches out to us to inquire about treatment options.”

Cost is another major barrier. In the U.S., a single IVF cycle typically costs from $12,000 to $25,000, and women over 35 often undergo multiple rounds.

“We’ve had patients come in with rolls of $5 and $20 bills — you can tell how hard they’ve worked to pull that money together,” Zhang said. “Some are unemployed or going through tough times, the cases where our doctors can’t even bring themselves to charge a consultation fee.”

There’s hope on the policy front for Californians. In September 2024, Governor Newsom signed Senate Bill 729, which expands insurance coverage for fertility care inlarge group health plans, starting July 1, 2025. At the federal level, a February executive order signed by President Trump aims to make infertility treatment more affordable nationwide.

But access to fertility treatments isn’t a guarantee of success. “Technological tools are a backup — not a plan,” Dr. Xia said. “Frozen eggs or embryos aren’t the same as fresh ones. Sometimes social media makes it a magic fix. It’s not.”

Based on her years of experience, Dr. Xia estimates that at least half of the women she sees have done little or no fertility planning. “Too many treat it as a last resort when it should really be the first step.”

This project was supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, and is part of “Healing California”, a yearlong reporting Ethnic Media Collaborative venture with print, online, podcast and broadcast outlets across California.