Philly's shame: City ignores thousands of poisoned kids

This story was originally published in The Inquirer with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

(Left to Right) Jihad and Murad sit with their dad, Andrew Irby, in the park. Irby worries about the future of his twin sons, who were both exposed to high levels of lead in their rented home.

When Aisha Stafford picked up her cell phone, the pediatrician sounded panicked.

"Whatever you're doing," he told her, "you have to stop." Take your son to the emergency room immediately, he insisted. Her son had a severe case of lead poisoning.

Stafford, a health aide, was working at a house in Germantown. She sped to her Brewerytown home, grabbed her 2 1/2-year-old son, Murad, and rushed him to St. Christopher's Hospital for Children, crying the entire way.

"I was so scared," she would later say about that May phone call.

Her husband, Andrew Irby, was seething. For months, Irby and the city's Department of Public Health had been after the landlord to fix the deteriorating lead paint in the 1920s-era house.

Murad and his twin brother, Jihad, moved into the house in March 2015. Eight months later, they tested high for lead. Now the amount in Murad's blood had skyrocketed to 46, nine times higher than the level that triggers medical alarms.

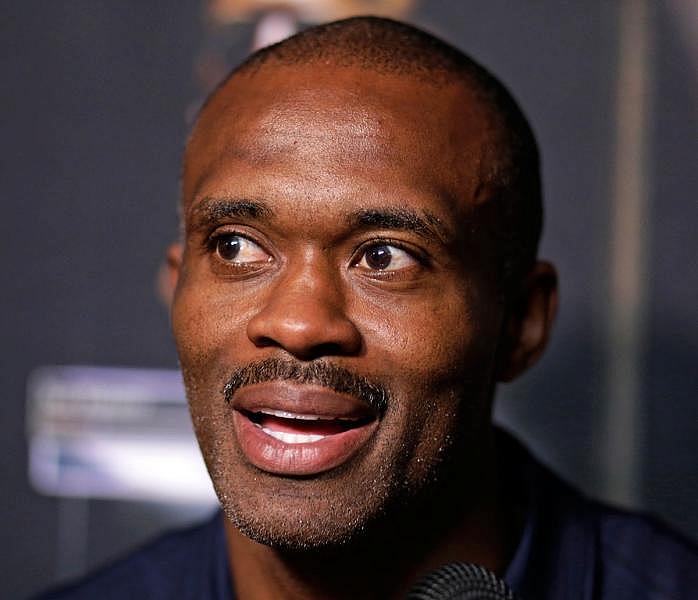

Irby dialed Marvin Harrison, the NFL Hall of Fame receiver from North Philadelphia. Harrison, who at one point in his storied career landed a $67 million contract with the Indianapolis Colts, is president of a company that owns more than 80 properties in Philadelphia, including Irby's.

Irby couldn't understand why the landlord refused to spend a few thousand dollars needed to make the home safe for his twins. The boys can barely speak, which the couple blame on lead contamination.

"They don't have a two-word-sentence vocabulary," Stafford said. "They cry and we've got to figure out what they want and give it to them."

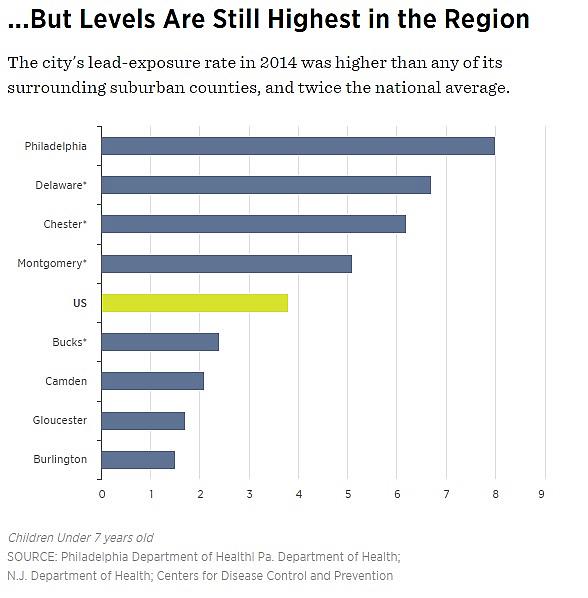

In Flint, Mich., national attention has highlighted the sudden spike of lead levels among hundreds of children from contaminated drinking water.

But in Philadelphia, thousands of children, year after year, are newly poisoned by lead at a far higher rate than those in Flint. In Michigan, the remedy was switching back to a safe water source.

Here, where the main culprit for this quiet and chronic scourge is deteriorating lead paint in old homes, the fix is elusive.

Last year alone, nearly 2,700 children tested in Philadelphia had harmful levels of lead in their blood. Lead poisoning can cause irreversible damage, including lower IQ and cause lifelong learning and behavioral problems.

Lead poisoning can be prevented, and cases have dropped sharply here and across the country. Yet Philadelphia continues to struggle to eradicate the problem, especially in the city's poorest neighborhoods. In some stubborn pockets of the city, as many as one out of five children under age 6 have high lead levels.

Philadelphia, which ranks among the top large U.S. cities at risk for childhood lead poisoning, is uniquely challenged. The city has a timeworn housing stock, with 92 percent of homes built before the country's 1978 lead-paint ban. And with the worst deep poverty of the nation's largest cities, many families find themselves trapped in toxic houses that made their children sick.

Research now shows there is no safe level of lead exposure for infants and young children.

"Even at very low levels, children can have trouble learning and have other problems with their brain function," said Dr. Kevin Osterhoudt, medical director of the Poison Control Center at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. "[It] robs them of their potential to achieve all they may have otherwise."

At a time of new urgency, the city does little to protect the majority of children exposed to lead.

Of the nearly 2,700 children with high lead levels in 2015, the Public Health Department checked on the houses of only the sickest of the sick, some 500 children.

Cities such as Baltimore, Cleveland, and others take action when a child's "blood lead level" reaches five micrograms per deciliter — the level the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has used since 2012 for public health officials to intervene. Philadelphia only steps in when a child is poisoned at level 10. But by then, it's too late, medical experts say. The damage is done.

City health officials say they want to do more but over the last three years have lost $3 million in federal funding out of a $9 million program and cut 40 of 65 positions in the Lead and Healthy Homes program.

The city did take a stab at prevention in 2012, enacting a law regulating homes built before 1978. Landlords renting to families with children age 6 and under must have their properties certified as lead-safe and provide proof to their tenants and to the Department of Public Health.

But landlords largely ignore the law. City health officials said they know of no fines collected for such violations.

The city has the nation's first Lead Court, created in 2002, to force landlords and homeowners to rid their properties of lead perils. Typically, the city drags only the most serious cases into Lead Court — 121 cases last year.

The city has housing laws and public health codes that could largely protect kids from being exposed to lead hazards, but they aren't enforced, said George Gould, a lawyer for Community Legal Services, which assists low-income families.

Public health officials say lack of money and staff are to blame. "We want to help every single kid and we want to prevent lead poisoning but we have to focus on the kids with the highest risk," said Palak Raval-Nelson, director of environmental health for the city's Department of Public Health.

Medical intervention and court orders to remediate homes only happen after public health workers learn that a child has been poisoned.

"We use children to determine whether or not there is dangerous lead paint in houses," Gould said. "We should not use a child like a canary in the coal mine."

"IT'S LIKE A CANDY SHOP"

On a warm September morning, Jalen Absolum joined his second-grade class in a West Philadelphia school yard, lining up for the 8:30 bell. At 9, Jalen was a head taller than his 7-year-old classmates.

Jalen was a toddler when his mother, Avril Absolum, and aunt moved into a house on Kenmore Road in the city's Overbrook section in 2009. Their new landlord was a longtime Philadelphia Common Pleas judge, Paul Panepinto.

Avril Absolum and son Jalen are very close. He looks to her for guidance as they work their way through flash cards.

Absolum used to live next door to Panepinto's parents. She said when she asked the judge if he knew of a house big enough for her family, he told her about the four-bedroom rental on Kenmore. Her sister and her sister's husband signed the lease.

After moving in, Absolum said she noticed flaking paint around the windows on the enclosed front porch and the bedroom she shared with Jalen. "I just thought the paint was a little old," she said.

About a year later, in 2010, Jalen's pediatrician discovered that Jalen had an alarming blood lead level of 29, up markedly from only 3 in an October 2008 test, public-health records show. The doctor immediately referred the boy to Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.

Suddenly, it became clear. Absolum, 50, remembered Jalen being drawn to window sills on the front porch. She would pull him away and see white chips around and inside his mouth.

"I did not know anything about lead at all," Absolum would later say.

She learned that lead paint chips taste sweet. "Once a kid starts eating the paint, it's like a candy shop," she said.

At the time, Jalen was only 2, a critical point in his development, as his brain produced 700 new neural connections every second. At that age, the toxic metal short-circuits the brain and disrupts pathways to developing sensory, motor, emotional, and cognitive skills.

Her son's case illustrates the terrible toll lead can wreak on a family and its future. "It feels like your child was robbed," Absolum said.

A Children's Hospital evaluation at the time found that at nearly 3 years old, Jalen had a vocabulary of only 20 words and could not put the words together. He exhibited "very aggressive" play and had "no back and forth play." He also was hyperactive and demonstrated a "lack of safety awareness," according to the evaluator, Dr. Jennifer Walton of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics.

"Though we may not know the reason as to why Jalen is delayed, lead toxicity is known to cause cognitive delays in children," Walton wrote.

Jalen's mother said she fears her sweet and gentle son will forever seem like a little boy. "All these things that a 9-year-old would have, he doesn't have," she said. "He's oblivious to everything around him."

Anytime a child gets a blood test for lead, the results are entered into a statewide database. A city nurse routinely checks the database to identify children with high lead levels. If a level is 10 or higher, a city health inspector visits the home to check for lead contamination, generally within a month or so.

In Jalen's case, it took five months for the inspector to visit. Health Department spokesman Jeff Moran said the agency had trouble locating the family because the pediatrician's office had provided an old address.

The inspector found flaking lead paint on the wood around seven windows, including the one in Jalen's bedroom. The city ordered Panepinto to paint or replace them within 10 days.

After 20 days, the city came back, found that Panepinto hadn't done the repairs, and told him in a Feb. 1, 2011, letter that it "is proceeding with legal actions."

As a judge, Panepinto occasionally handled Lead Court cases over the years and for a time had been supervisory judge of Family Court.

Panepinto did not reply to numerous messages left at his office and his home. But a lawyer for the judge, Paul Masciantonio, wrote in a recent email: "In 2011, Judge Panepinto was notified to remediate the premises and he complied. Judge Panepinto had no prior knowledge of any issues with respect to this premises and no knowledge of any children residing at this property. No children should have been residing at this property."

On Feb. 25, 2011, the Health Department determined that Panepinto had remediated the lead and the case was closed that April.

A public health staffer helped arrange speech and occupational therapy for Jalen.

"The city was actually very, very helpful afterward," Absolum said.

Absolum said her son likely will spend his remaining school years in special education, which economists estimate costs public school systems about $17,000 a year extra per child.

He reads at a kindergarten level, she said. He is impulsive, runs into the street, and can't read emotion on others' faces.

Doctors use delayed to describe Jalen, a word Absolum believes gives parents false hope. "This is not a delay — it's a permanent condition," she said. "It's irreversible and the sooner parents understand that this is permanent, it's better for them to understand."

Absolum said she had to go through "a grieving process" to accept that Jalen faces a lifelong struggle. She still can't help but compare her 9-year-old son to the children of her friends and to those she cares for as a nanny for families on the Main Line.

"It's very hard for [me] to see other friends with kids who are doing this and doing that and they just have it together and you can't talk about it," she said.

HIGHEST LEAD LEVEL IN YEARS

Andrew Irby got Marvin Harrison on the phone and told the Hall of Famer that one of his sons was in the emergency room, extremely sick from the chipping and peeling paint in the home on Ringgold Street.

Harrison, a former Roman Catholic High star, who used to be what Irby called one of his "favorite NFL legends," brushed him off, saying most houses in Philadelphia have lead in them, Irby said.

He blamed Harrison for making his kids sick and wanted him to do something immediately. The conversation turned heated, with both men swearing, Irby said.

Harrison did not return several phone calls or reply to messages from a reporter.

At St. Christopher's, doctors did tests on Murad but fortunately did not find chips of lead paint in his stomach nor was he anemic, which is associated with lead poisoning. Murad and Jihad were particularly vulnerable to lead hazards because they were born premature, each weighing 3½ pounds and exhibiting an anemia-related disorder called hemoglobin Bart's.

Because Murad's lead level was so astronomical, at 46 — the highest the public health department had seen in years — the hospital alerted the city's Department of Human Services. A staffer there told Aisha Stafford that she had to find a safe place for both of her boys to live. Stafford took them from their $725-a-month, redbrick rowhouse on a slice of a street in Brewerytown and sent them to live with her sister in South Philadelphia. Both boys started to get speech therapy twice a week.

Stafford felt trapped, unable to come up with the two months' rent and security deposit typically required to lease a new place.

Harrison, 44, is president of Harrison Inc. and Morris-Harrison Inc., which together own 85 properties, including a sports bar, Playmakers, and Chuckie's Garage. Most of them are within 15 blocks of one another in Brewerytown. Some are renovated with new windows and gleaming hardwood floors. Some look aged and worn. Other properties are vacant lots, a few with rusted old cars.

NFL Hall of Famer Marvin Harrison owns 85 properties

Harrison is practically a king on these streets, where he grew up and never really left. This rough-and-tumble neighborhood, about eight blocks up a hill north of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, has one of the highest rates of childhood lead poisoning in the city, 13 percent, an analysis of federal data shows. Just a little farther north is ground zero: Strawberry Mansion, where 21 percent of children tested had lead poisoning.

In January, four months before the emergency-room visit, a city health inspector found chipping lead paint and residue throughout the Ringgold Street house. The Health Department, which requires landlords to use certified workers to remove lead hazards, ordered Harrison to make the repairs within 30 days.

Inspectors flunked the house again for lead in late February.

In May, the Health Department nurse learned that Murad's blood-lead level had spiked to 46, sparking the ER visit. Jihad's was also extremely high, at 23.

Within a day, department staffers were at the home. Stafford told them that Harrison had sent over an uncertified worker who did repairs "incorrectly," according to a court record. "My child was still able to peel the paint off the window sill — it was horrible," she later said in an interview.

The Health Department did a "super clean" at the rental house to remove all lead chips and dust, and 12 days later had workers start to prime and paint all the unsafe surfaces.

When Harrison got word of the city's abatement work, he went to the Ringgold Street house to ask the workers what they were doing there, court records show. The next day, he told their supervisor he already had completed most of the repairs.

But "it wasn't to the city's liking," said Harrison's lawyer, David Denenberg. "We didn't ignore it."

But city inspectors still found lead, and completed the work. The city took Harrison and Harrison Inc. to Lead Court later that May.

It wasn't his first involvement in Lead Court. Years earlier, in a house about two blocks away on West College Avenue, a 1-year-old girl had tested high for lead. After the house failed a second inspection, the city took Morris-Harrison Inc. to court. The company made the repairs.

Unlike Philadelphia, other cities target first-time offenders to prevent future cases. In Portland, Ore., once a landlord is flagged for a lead-poisoned child, city workers inspect any other homes owned by that landlord. Rochester, N.Y., requires that all rentals be inspected for lead every three years; in hot-spot neighborhoods, Rochester tests all homes before they can be rented.

In Philadelphia, property owners can rent homes without a city inspection for lead hazards or any violations. They simply pay $50 to get the required rental license. Landlords have only bothered to get a license for about one-third of the city's 250,000 rentals. They are almost never penalized.

Since 2012, landlords have to provide proof their homes are lead-free or lead-safe for families with young children. But most fail to provide the certificate to the public health department and the tenant, and the city doesn't hold them accountable. In fact, less than 1 percent of landlords comply, public health officials estimate.

Harrison Inc. never filed the certification with the Health Department before he rented to Stafford and Irby in 2015, court records show.

In this case, the city did ask a Lead Court judge in October to hold Harrison personally accountable, not just Harrison Inc.

The city requested a judge to fine them $2,000 for every day that Harrison and Harrison Inc. had been in violation of the certification law.

The city also asked that Harrison and Harrison Inc. be fined $300 a day for each day they had collected rent from Stafford and Irby while failing to comply with a February lead-abatement order.

Denenberg said his client is not responsible. "Marvin Harrison does not own the house. Harrison Inc. owns it."

Denenberg said that Harrison and Harrison Inc. are not one and the same and that Harrison did not sign Irby and Stafford's lease.

The city argued that Harrison Inc. is Marvin Harrison's "alter ego," and was formed to mask his ownership and insulate him from liability.

The city Health Department shelled out $2,297 to remove the lead hazards at the Ringgold Street home. The city asked a judge to make Harrison foot the bill. Denenberg said Harrison Inc. has offered to pay. A hearing is scheduled for Tuesday.

Last month, the Irby twins moved back home while their parents search for another place to live.

A TRAIL OF TOXIC CONFETTI

The city relies on Lead Court to hammer landlords into compliance. But the system is far from perfect. And in some cases, it's ineffective, particularly when up against landlords who repeatedly shrug off city laws.

Take the case of Simon Bouhadana, of Brooklyn, president of Home 4 Rent, which owns 53 properties in Philadelphia.

Home 4 Rent rented a house in the city's Germantown neighborhood to Gregory Jackson and his longtime girlfriend, Sophia Pope, for $750 a month. Jackson and Pope moved into the two-bedroom house on Bonitz Street with their four young children in March 2014. At the time, the couple's youngest son, Vaughn, was only 6 months old.

That meant Home 4 Rent, under the city's 2012 law, was required to hire a trained professional to take dust samples from the house and certify that the house was lead-safe before the family moved in. The landlord was supposed to file the certificate with the Health Department and provide a copy to Jackson and Pope to sign.

The city said the landlord didn't file a certificate.

Jackson and Pope had no idea that the house was toxic. Tests by the Health Department would later show lead paint was everywhere: on the walls that Vaughn hugged as he learned to walk, on the stairwell banister that he gripped with tiny hands, in the basement that doubled as a play space on cold and rainy days, in his bedroom, on the windowsills in the living room where Vaughn liked to perch — his place to peek out on the world.

Simon Bouhadana of Brooklyn, president of Home 4 Rent, which owns 53 properties in Philadelphia.

By age 2, Vaughn's blood lead level was a 12.

"I was super stressed because we didn't have the money to just up and move," said Pope, 32, who earns $10.45 an hour as a manager at a Burger King. Jackson, 41, works in an insurance company mail room and makes $13.69 an hour.

He pressed Bouhadana to have the house fixed. But Jackson said Bouhadana seemed indifferent, using the landlord mantra that all old houses have lead, Jackson recalled.

"I’m like, 'Oh, OK, all old houses have lead, but OK, you don't live here,'" Jackson said. "'You live in New York. And your kid doesn't have lead. My kid has lead.'"

Bouhadana did not return three phone calls or respond to a note left at his Brooklyn home, where a Mercedes sat in the driveway and a woman told a reporter, through an intercom at the front door, to leave.

In early November 2015, the city sent Home 4 Rent a letter ordering the landlord to remove the lead hazards or face fines. If not, Jackson and Pope had the right to withhold rent and the landlord could not evict them, under the city health code.

It was only then that Bouhadana drove down from Brooklyn. He looked Jackson in the eye and shook his hand, "man to man," promising to get workers out to remediate, Jackson said.

Gregory Jackson and longtime partner Sophia Pope with their son Vaughn Jackson, 3, at their home in Germantown. Sophia and Gregory are happy that Vaughn is once again more active and alert, but they have concerns for his future development.

Before parting, Jackson said he handed Bouhadana November's rent in cash.

November came and went and no work was done.

In December, the city moved to take legal action against Home 4 Rent.

The city told Jackson and Pope in a letter that the landlord was "prohibited from collecting rent" and "cannot evict you through court action."

A few days after Home 4 Rent was issued a court summons, three workers showed up at the rental house. Under local and federal laws, those workers were required to be certified in lead-paint removal and follow strict rules. For example, work cannot be done when children are present. Nor can workers use open-flame torches, sandpaper, and chemicals to remove lead paint.

One worker, however, began using a blowtorch to burn paint from the walls, windowsills, and baseboards, Jackson and Pope said. Another splashed the walls with paint stripper. As the paint began to bubble and crack, the workers scraped and sanded it off.

Jackson, with the city's guidelines in hand, tried to stop them. "Look, it says directly on the paper, 'Warning, do not burn anything.' You are contaminating everything," he said he told them.

Jackson said the workers kept on, burning and scraping, leaving a trail of toxic confetti.

Frustrated and panicked, Jackson took cellphone photos and texted them to the Health Department. The kids were sent to a relative's house a few blocks away.

The city quickly issued a "cease and desist" order to Home 4 Rent that read, in part: "The practice of burning leaded paint and doing lead hazard control while the family is present must immediately stop. When lead paint is burned, it aerosolizes and exposes everyone in that household environment to a high concentration of lead by the most efficient route of exposure, inhalation."

Jackson and Pope said they were deeply worried for their kids. So was the Health Department, which urged them to get all four kids retested for lead.

It came as no surprise that Vaughn's lead level had climbed to an 18. And the amount of lead in their oldest son's bloodstream rose to a 6, according to test results.

Jackson and Pope withheld December's rent for the contaminated home and continued to look for a new place to live.

In early January, a lawyer for Home 4 Rent filed eviction papers against them in Landlord-Tenant Court.

The couple said they only learned about the eviction action when a prospective landlord, after doing a background check, told them he was wary of renting to them.

Home 4 Rent claimed that Jackson and Pope owed it $2,059 — $1,500 for December and January rent, $114 in late charges, and $445 in legal fees.

At the Landlord-Tenant Court hearing, the eviction case was dropped. Bouhadana and Home 4 Rent could have been fined up to $300 a day for trying to evict them, but they were not.

After the family moved into a different house in March, they repeatedly asked Bouhadana for their $750 security deposit, but he refused, Jackson and Pope said.

Bouhadana personally faced as much as $4,500 in possible fines for failing to eliminate the lead hazards at his Bonitz Street house. On April 7, a judge in Lead Court penalized him and Home 4 Rent $500 and gave 30 days to pay. The fine remains unpaid, court records show.

The Health Department deemed the house in compliance with health codes for lead in June and a judge closed the case.

The long, toxic odyssey of the Bonitz house appeared to be over, but a reporter wanted to be sure.

A view of the 1900 block of Bonitz Street, where Gregory Jackson and Sophia Pope's youngest son was poisoned by lead paint in a home they rented. More than 90 percent of the houses in Philadelphia were built before the 1978 lead-paint ban.

NEW TENANTS, NEW TEST FOR LEAD

By the end of the summer, new tenants had moved in: Juanita Mickens, 94, and her 56-year-old niece, Camilla Hardee Mickens.

On a visit last month, it was clear the living-room walls, once scorched by flames to a brown-yellow hue, had been repainted, now steel blue. The trim and baseboards had a fresh coat of white paint.

It looked as if the landlord had indeed taken care of the lead problem, just as the city had concluded. But friction from opening windows and doors can wear off surface paint and reexpose underlying lead paint, especially from substandard work.

The Mickens women were having a kind of housewarming party for extended family, and welcomed in a reporter. They crowded into the living room to watch a movie and eat pizza, loudly talking over its sound track. A 4-year-old boy, the great-nephew of Camilla, sat on a velvety new couch.

The Mickens women were told of the home's toxic history and gave permission for a swipe test, using a "lead check" swab from a hardware store. The swab turned red, indicating lead paint. They accepted a reporter's offer to have the home tested by experts for unsafe levels of lead.

In September, a state-licensed, lead-risk assessor, Criterion Laboratories of Bensalem took dust-wipe samples throughout the house.

Four of the eight areas tested for lead dust came back as hazardous: the basement floor, a stairwell step leading up to the second-floor bedrooms, a bedroom windowsill, and the foyer floor at the front door.

A sample from the floor of the unfinished basement, where the previous tenants' kids often played, tested at 766 micrograms of lead in dust per square foot — 19 times higher than the residential limit set by federal regulations.

Lead dust at dangerous levels, invisible to the eye, was lying in wait for its next likely victim.