Politics trumps health in state’s response to alcohol crisis

Ted Alcorn reported this story while participating in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 Impact Fund for Reporting on Health Equity and Health Systems, which provided training, mentoring, and funding to support this project.

Other stories include:

AN EMERGENCY HIDING IN PLAIN SIGHT

Every door is the right door: Doctors can do more to treat alcohol dependence in New Mexico

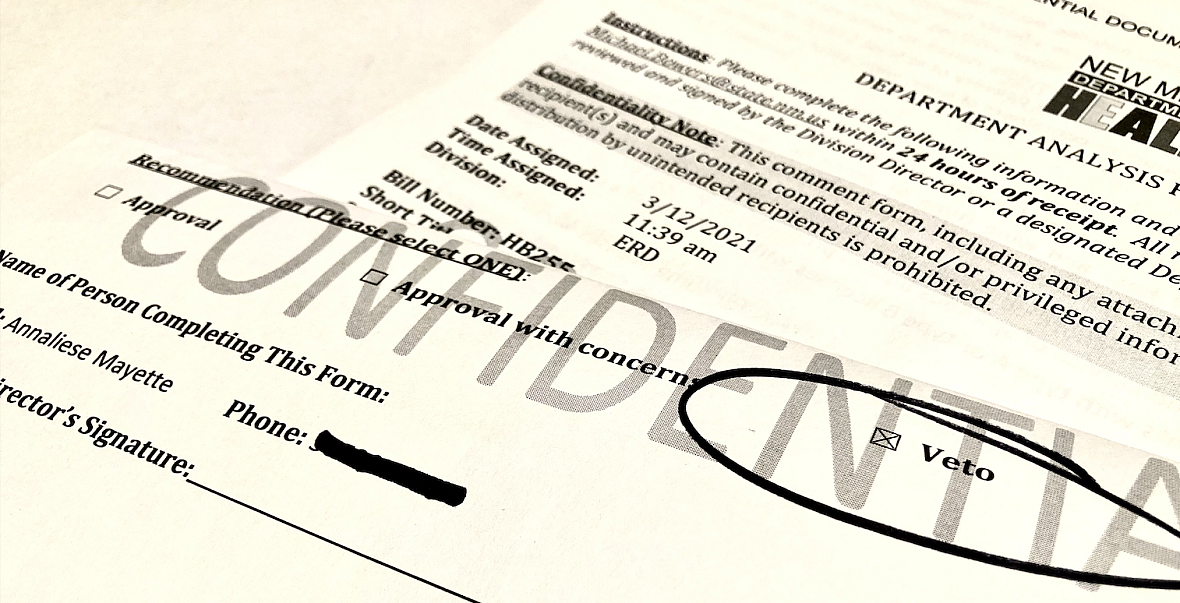

New Mexico's alcohol epidemiologist, Annaliese Mayette, recommended the governor veto landmark alcohol legislation that expanded access to alcohol. It is unclear whether her recommendation made it to the governor.

In February 2021, as New Mexico lawmakers considered landmark legislation to loosen restrictions on alcohol sales, the state’s alcohol epidemiologist Annaliese Mayette set out to assess the bill.

Excessive drinking kills people in New Mexico at a faster clip than anywhere else in the country, and the proposal would make it easier for restaurants to serve liquor and allow residents to order alcohol delivered directly to their homes. The intention was to buoy hospitality businesses hard-hit by pandemic-era shutdowns.

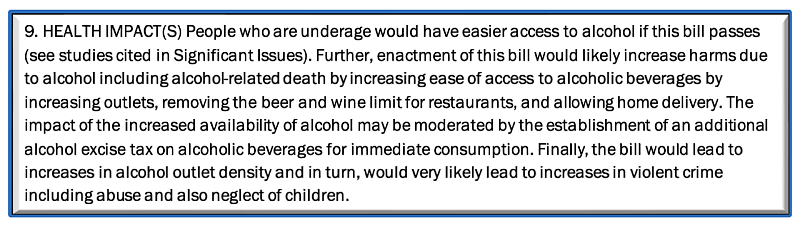

Drawing on scientific research and her expertise, Mayette warned in a memo that the legislation would “give underage drinkers more access to alcohol” and “would likely increase harms” including violent crime and child abuse.

Her memo was meant for the Legislative Finance Committee, which compiles analysis from state agencies to educate policymakers on the likely consequences of voting a bill into law. Mayette sent a draft to higher-ups in the health department — but they never passed it on, so her concerns were missing from the committee’s report.

Lawmakers would go on to pass the bill with little to no public discussion of how it would affect residents’ health.

The final bill also expanded the hours businesses could sell alcohol, contrary to U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations about how to curb excess drinking, and provided millions of dollars of tax relief to liquor licensees.

New Mexico’s alcohol epidemiologist wrote an analysis for lawmakers about the potential harms of alcohol legislation in 2021, but the memo was never passed on by her supervisor to lawmakers.

So, Mayette drafted a confidential analysis for Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham, recommending she veto the bill.

Lujan Grisham instead signed it into law.

Drinking takes the lives of nearly 2,000 New Mexicans each year, more than fentanyl, heroin, and methamphetamines combined. The death-rate is nearly three times the nation’s, higher by far than any other state. As lawmakers wake up to the crisis, they are looking to the Department of Health for guidance.

But a review of internal records and interviews with a dozen current and former health department staff show what expertise it possesses has long been muzzled or ignored.

The department’s politically appointed leaders have often disregarded career scientists and rejected repeated requests to build a program wholly devoted to reducing alcohol-related harms. Although the agency has closely documented alcohol’s harmful impacts on the state, it has largely failed to translate that research into action.

Former senior officials say the state government’s feeble approach stems from a dysfunctional structure that fragments activities related to alcohol across agencies — and from a governor who seems unswayed by evidence of the problem’s urgency.

Dr. Abinash Achrekar, who served as Deputy Cabinet Secretary of Health in 2019, said “the data were there, the interest of the department was there, but there wasn’t any political will to act.”

MUZZLED AND IGNORED

The health department is the state’s largest agency with nearly 4,000 positions across eight divisions. For decades, its Epidemiology and Response Division has quantified the harms alcohol does to the state: it began issuing annual reports about substance abuse in 2004 and each starts with a chapter on alcohol-related deaths.

That year, the C.D.C. began offering states grants to hire alcohol epidemiologists and New Mexico was the first awardee.

But the health department has never built a dedicated program focused on reducing excessive drinking. Greatest expertise likely resides in the epidemiology division’s Injury and Behavioral Epidemiology Bureau, whose 60 staff focus on measuring and preventing suicide, violence, and other injuries, many of which involve alcohol. In the separate Public Health Division, employees educate local communities about the harms of excess drinking, among many other topics.

These scattered personnel rarely work together. And whereas the department has dozens of employees focused exclusively on opioid overdose deaths and tobacco control, it has never expanded the staff dedicated to alcohol beyond a single epidemiologist.

State taxes on alcohol raise about $50 million annually and could support preventive measures, but less than half is directed to counties for alcohol prevention and treatment. Those activities are overseen by the executive branch’s budget-making agency — the Department of Finance & Administration (DFA) — and are not always evidence-based.

Wayne Lindstrom, who led the Behavioral Health Services Division from 2014 to May 2019, said DFA “has no competence around alcohol and alcohol-related problems.” In 2016, he promoted legislation that would have transferred management of county alcohol prevention activities to his division but the proposal made little headway.

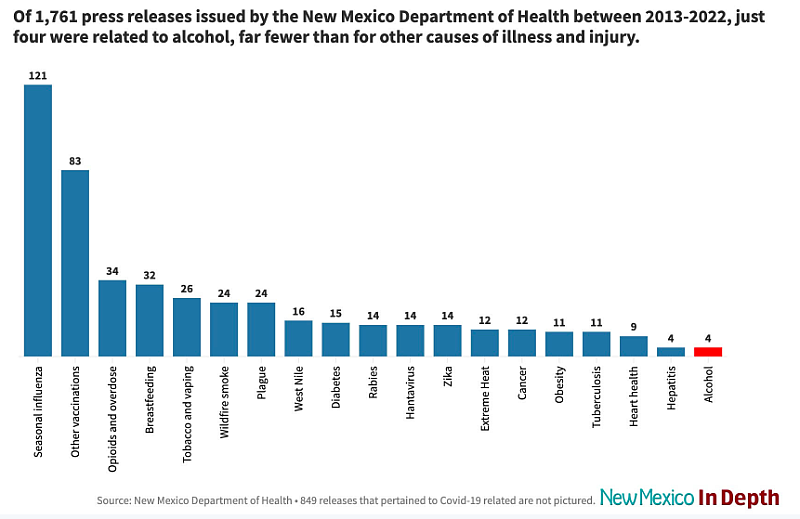

Another measure of the health department’s disinterest in alcohol is how infrequently it communicates about it to the public. A New Mexico In Depth analysis of over 1,750 departmental press releases issued since 2013 found just four related to alcohol. That’s a fraction of the number the department issued about seasonal influenza (121), opioids and drug overdose (34), plague (24), and even rabies (14).

Department leaders said they issue press releases when the incidence of a disease or injury is rapidly increasing, so the number of releases is not an accurate gauge of the department’s priorities. But the public information office has issued no releases about alcohol in the last three years, even as alcohol-induced deaths in the state and nationwide have spiked.

In an interview, Aryan Showers, director of the department’s Office of Policy and Accountability, called alcohol a “difficult” problem “because we have sort of gotten to a point where we live with it.”

Showers, who previously worked as a lobbyist and staffed political campaigns but was not trained in public health, oversees policy and strategic planning for the department. She said she withheld Mayette’s bill analysis in 2021 because the Legislative Finance Committee never specifically requested input from the health department. “We can’t actually force the legislature to take our analysis,” she said. “I can’t arm wrestle them over it.”

Helen Gaussoin, a principal analyst for the Legislative Finance Committee, wrote in an email, “it is safe to assume the analysis would have been included in the [committee’s report] had it been received.”

Through a spokesperson, then-Health Secretary Dr. Tracie Collins declined to comment.

Rep. Joanne Ferrary, D-Las Cruces, who initially opposed the 2021 legislation, was disturbed to learn the health department had produced a critical analysis she had not seen prior to her vote. The bill’s supporters wore her down, she said. “I finally gave in to thinking that they might be right. But that’s because we didn’t have the information from the [Department of Health].”

Sen. Gerald Ortiz y Pino, D-Albuquerque, said the health department’s input “might have changed the debate.”

A VACUUM OF LEADERSHIP

Health departments in other states adopt more muscular approaches towards alcohol, fielding larger staffs, dedicating more dollars, and pursuing more aggressive policies.

In Oregon — where the alcohol-related death rate is above the nation’s though still well below New Mexico’s — the state health authority has four staff fully devoted to preventing alcohol-related harms and recently spent over $800,000 on a statewide media campaign urging residents to “Rethink the Drink.” The authority also routinely lobbies the legislature to increase alcohol taxes, which experts say are crucial for reducing excess drinking.

In New Mexico, internal documents show the Epidemiology and Response Division has repeatedly asked to hire additional staff for a program focused on alcohol but the health department’s leaders have turned them down.

Achrekar supported the creation of an alcohol program in the first year of the Lujan Grisham administration, he said, because substance use was the primary preventable threat to New Mexicans. But the governor’s office did not include it in their budget request. “We were told that this is not where the governor wants to go,” he recalled. When the next fiscal year’s budget cycle began, “we did not even approach the governor’s office with anything with alcohol because it was so summarily declined the year prior,” he said.

The division’s latest request — for two additional epidemiologists to evaluate changes in alcohol laws and recommend “evidence-based population level” preventive strategies — was not included in a September 1 letter listing the department’s appropriations request for next year’s budget, despite a state surplus of more than two billion dollars. Asked for comment, a department spokesperson said that all personnel requests, including this one, were “under review.” Last week, a spokesperson for the governor said that funding for the positions would be in the administration’s budget proposal in the upcoming legislative session.

Showers defended the decision not to build an alcohol program in the last four years, saying the health department had a lot on its plate. “We have a thousand things that everyone thinks are the most pressing priorities in public health,” she said.

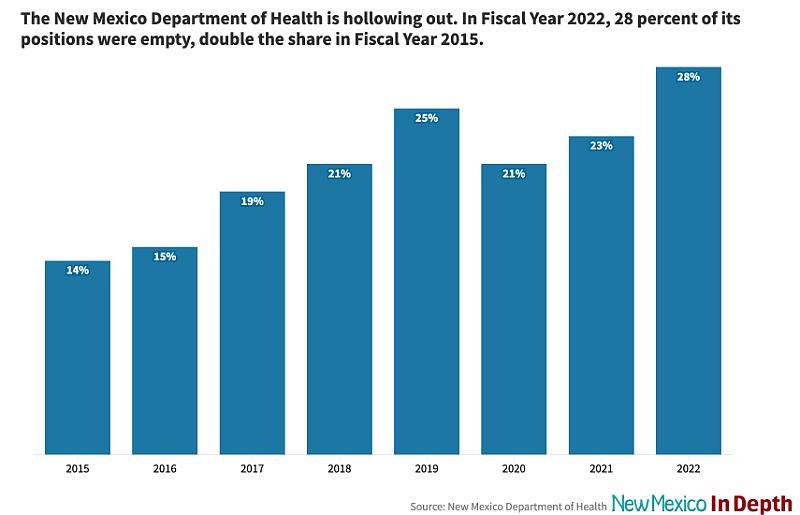

Part of the strain on the department is staff turnover, which handicaps the department’s ability to respond. According to a spokesperson for the department, 28 percent of its positions are currently empty, double the share in 2015.

The churn has affected leadership, too. The department is under the acting direction of Dr. David Scrase, who took up the reins in mid-2021 on top of his existing role as Secretary for the Human Services Department. The Epidemiology and Response Division hasn’t had permanent leadership since July 2022, when Dr. Christine Ross departed.

Historically the role of division director has been “classified,” meaning state civil service rules protect the person from being fired without cause, and thus allow more independence from political interference. But the role is currently filled by an acting director, Laura Parajon, who also juggles the role of Deputy Cabinet Secretary of Health, and is appointed by and effectively works at the pleasure of the governor.

In July, Mayette left the role of alcohol epidemiologist for another job. For more than four months — while New Mexican newspapers and legislators gave attention to the state’s drinking problems — the health department’s sole position wholly focused on alcohol sat vacant.

IN THE SPOTLIGHT, CAUGHT FLAT-FOOTED

Legislators appear interested in responding to the crisis. Since August, at least four legislative committees have discussed it, most recently the Revenue Stabilization and Tax Policy committee, which debated raising the state’s alcohol tax and fully devoting its revenues to treatment and prevention.

But state legislators have little experience reining in excess drinking and are looking for help. Ferrary, for example, proposed the governor establish a task force of experts to recommend further actions.

When legislators have turned to the health department, they’ve received little practical guidance. At an August 24 legislative hearing, when Sen. Antoinette Sedillo Lopez, D-Albuquerque, asked for recommendations, Showers only suggested the state “improve surveillance and devote more resources to really monitoring what is going on.”

Achrekar disagreed. “We don’t need data documenting the problem. The problem is clear,” he said.

Similarly, Lindstrom said evidence-based means for reducing excess drinking were well known. “If you can limit accessibility and supply, you can reduce problems associated with alcohol use — that’s demonstrated over and over again — but there’s been no will to put those kinds of limits in place.”

Lujan Grisham has touted her tenure running the state health department from 2004 through 2007 and was briefly considered for a role in President Joe Biden’s cabinet as his health secretary. But Lindstrom and Achrekar both attributed New Mexico’s lack of initiative to address alcohol to the governor herself.

Lindstrom, who she held over into her administration for several months before dismissing him, said: “She has her agenda, and it’s her way or the highway.”

Achrekar, who left the cabinet after a year, said, “I don’t think she is willing to look at data that contradicts some sort of narrative that she has.”

A spokesperson for the governor disputed this, citing the administration’s efforts to expand access to substance abuse treatment and an interagency meeting the administration began in 2019 to coordinate efforts across government to curb alcohol-related deaths. The workgroup has not met in six months.

In September, after state legislators began calling for action, the spokesperson emailed New Mexico In Depth that the administration was seeking $5 million in next year’s budget “to address alcohol misuse.” This would be a significant uptick in what the department devotes to alcohol prevention, although Boston University School of Public Health Professor David Jernigan said it was still “a pittance.”

Showers said the department didn’t have a plan for the money yet. It will likely focus “on prevention, health promotion, those kinds of strategies,” she said. “We don’t have all the details sorted out.”

[This article was originally published by New Mexico In Depth.]

Did you like this story? Your support means a lot! Your tax-deductible donation will advance our mission of supporting journalism as a catalyst for change.