Rebuilding after Harvey: 'You have to build their lives — not just their homes'

This article was produced as a project for the University of Southern California Center for Health Journalism’s National Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

Christmas miracle arrives for family struggling to rebuild after Harvey

PART 4: Will small towns recover after Harvey? It's a matter of if, not when

11 years have passed since affordable housing was built in Victoria; advocates say change needed

Part 3: Mold, bedbugs, rising rents — the reality of renting post-Harvey

Part 2: 'Willful blindness:' After Harvey, a Victoria family feels forgotten

Volunteers help Vietnam veteran living in car after Harvey

More than one year after Harvey, Vietnam veteran still living in his car

Hurricane Harvey exposed the gap between people who could afford to rebuild — and everyone else

Reporter column: We listened to your stories about life after Harvey. Now it's your turn to act.

'We just got so much work to do': Number of homeless outside of shelters triples in Victoria

Overgrown grass covers the baseball diamond and over home plate at the little league field in Bloomington.

(Photo: Angela Piazza/Victoria Advocate)

Theresa Martinez can still remember the sound of parents’ cheers and the smell of pizza and nachos sold at the concession stand at the Little League field in Bloomington, a rural community deep in the heart of South Texas.

She played on that field as a child, and coached her own children in games there decades later. Martinez, now 50, remembers how on one particular day, a little boy hit a home run – and instead of sprinting to home plate, he ran home, literally, to a mobile home about a block away.

“He had hit the ball, and I was saying, ‘Go! Go!’” she recalled. “And he took off and he ran. And after third base, he ran home!”

Even though it happened more than 25 years ago, Martinez laughs just thinking about that day.

But that happened at a time when children still played on Bloomington’s Little League field. It wasn’t overgrown with grass and weeds. Buzzing cicadas and the occasional passing train weren’t the only signs of life there.

Yet residents estimate it’s been at least five years since any Little League team played on that field, a sad reality community members say needs to change.

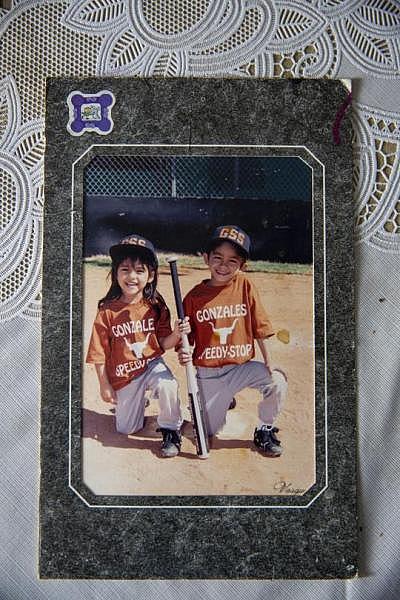

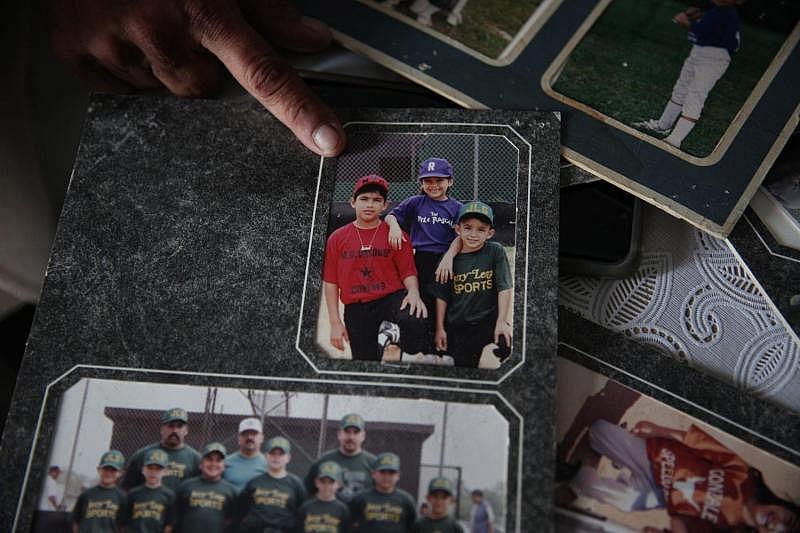

Theresa Martinez shows old photographs of her kids in Little League. (Photo: Angela Piazza/Victoria Advocate)

Because in previous decades, the grassy lot was more than just another Little League field. Like in many of America’s small towns, the field was once the heart of Bloomington, a community of 2,500 residents nestled between ranches, cotton and corn fields in rural Victoria County.

Today, however, the Little League field is largely forgotten, a sad reflection of the town itself. Like many South Texas small towns in oil-rich Gulf Coast, life started to change for Bloomington when the oil industry crashed in the 1980s. In the decades since, businesses abandoned buildings downtown, young adults fled to larger cities and residents struggled with the harsh realities that come with limited job opportunities in town.

Then Harvey hit, displacing an estimated 35 percent of the town’s residents. One year later, residents fear those in power may forget the unincorporated town, where there isn’t a local government to fight for grant money or resources to rebuild.

Vines grow up chain-link fence surrounding a littered dugout. Overgrown grass covers the baseball diamond. (Photo: Angela Piazza/Victoria Advocate)

But local residents won’t let Bloomington be forgotten if they can help it. They know that homes must be rebuilt. Businesses need to reopen. But they also realize that rebuilding Bloomington is going to take a lot more than simply repairing leaking roofs or replacing soaked drywall.

“You have to build the community,” said Danny Garcia, who grew up in Bloomington. “You have to rebuild their lives – not just their homes.”

And that’s where the Little League field comes in.

‘IT ALL STARTED AT THE LITTLE LEAGUE FIELD’

As a child in the 1960s, Garcia, who now serves as the community’s county commissioner, remembers Bloomington as a town not unlike Mayberry from “The Andy Griffith Show.”

Plants like DuPont and Union Carbide had recently moved to the area, offering decent-paying jobs that didn’t require a college degree. At that time, Bloomington’s downtown was home to at least a dozen businesses, including a movie theater, post office, dry cleaner, grocery store, cafe, drug store and several gas stations, said Garcia.

Theresa Martinez shows old photographs of her kids in Little League in Bloomington. (Photo: Angela Piazza/Victoria Advocate)

It was during that era that Garcia learned to win – and lose – on the baseball field. Back then, Little League was so popular that there wasn’t enough room for all the families to park around the field; it seemed as if every child in town played, no matter the parents’ financial status.

Decades later as an adult, Garcia also took his son and daughter to the same field. During one particular game, he was roped into joining the Parent Teacher Association. Eventually, he was spurred to run for local school board – and won.

“It all started at that Little League field,” Garcia said. “Little League is the easiest way I’ve seen to bring people together.”

But decades later, neither the Little League field nor Bloomington is what it once was. In the town, there are no doctors’ offices or banks. And even though an estimated 17 percent of the town’s residents live below the poverty line, there are very few programs for children – not even a daycare or after-school program. The closest programs are almost 15 miles away.

It wasn’t always that way. Martinez, who now works as a case manager helping people recover from Hurricane Harvey, remembers playing Little League, volleyball, basketball and track when she was a child. And once she became a mother, she coached all five of her children in Little League practices and games.

After her children grew up, she kept volunteering to run the Little League program. She made sure the team had a charter, which allowed it to participate in official Little League events. Besides roping her two sons into coaching, she also maintained the field, painted the concession stand, ordered uniforms, made up game schedules and collected fees.

Starting about a decade ago, however, involvement from parents in the town dwindled. Today, many Bloomington families teeter on the poverty line, and don’t have $40 needed to sign up each of their children, she said.

Because some of those families have few resources makes it all the more important to support their kids, she said. Sports teach children about teamwork, leadership and sportsmanship – lessons that help kids succeed in school and later as an adult.

And once children are involved, their parents will follow, too. Those are the parents who will host fundraisers, coach teams and be involved with the schools. They will help their children exercise and hopefully grow a healthier Bloomington.

Theresa Martinez, 50, shows old photographs of her kids in Little League. Martinez was involved with the youth sports program in Bloomington for about three decades and is struggling to get youth sports started again. (Photo: Angela Piazza/Victoria Advocate)

That’s why Martinez is again taking things into her own hands, organizing a group of community members to try to boost programs for children. They’re starting with soccer – which is cheaper than trying to get the Little League charter back. It won’t fix all of Bloomington’s problems, she said, but it’s a start.

“If we would all just come together, we would have something good for these kids,” said Martinez.

[This story was originally published by Victoria Advocate.]