Residents left in the dust as developers rush to mine D.C.’s affordable housing stock

This is part 2 of a special series about the effects of gentrification on the health of the residents of Washington, D.C. Check out part 1 of the series here. This series is supported through a journalism fellowship with the Center for Health Journalism at the Annenberg School of Journalism at the University of Southern California.

Other stories in this series include:

For many black Washingtonians, gentrification threatens housing and health

Freddie Allen/AMG/NNPA

Leon Lightfoot, a truck driver and longtime resident of Washington, D.C., was anxious to move back into his newly-renovated apartment in the Northeast section of the city. For Lightfoot, his wife and son, and many of the other residents of Dahlgreen Courts Apartments, the rehab signaled that city officials and real estate developers were willing to invest in the low-income, Brookland neighborhood and the people who had lived there for decades.

But, in 2011 and 2012, as the Mission First Housing Group rushed tenants back into unfinished apartments covered in thick layers of dust; with ill-fitting windows that didn’t open or close properly; and holes so large in their floors that you could see the apartments below, some Dahlgreen residents began to question the developer’s true motives.

Today, a new lawsuit alleges that Mission First was so negligent in the management of the Dahlgreen Courts acquisition that the developer not only wrongfully evicted residents, but also exposed families to black mold and other toxins that made some of them sick.

The dispute shines a light on how gentrification appears to be affecting the health of low-income residents in Washington’s rapidly gentrifying neighborhoods.

Some Dahlgreen residents believe that for Mission First it was always about the money.

While tenants like Lightfoot speculated that Mission First hurried them back into unfinished units in an effort to drive some residents out of the building by illegally increasing their rent payments, others have suggested that the developer, running low on cash after starting the renovations, needed to generate revenue to keep the project afloat.

Despite repeated requests for interviews, Mission First did not respond to offer comments for this story.

In 2010, the Mission First Housing Group acquired Dahlgreen Courts Apartments with help from the D.C government. The nonprofit received a tax-exempt bond and low-income housing tax credit allocations through the District of Columbia Housing Finance Agency.

The Dahlgreen Courts Apartments are two stately and imposing red brick structures—two towers, built in the classical, revival style. Located near the corner of 10th Street and Rhode Island Avenue, the historic buildings remind you of the Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books.

The District of Columbia’s Housing Finance Agency approved plans that would allocate over $9 million toward substantial rehabilitation and upgrades to Dahlgreen Courts, according to the lawsuit.

At the time, Dahlgreen Courts was one of the closest apartment buildings to the Rhode Island Avenue-Brentwood metro station, which the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority described as “one of the most dangerous stations in the system,” according to the Washington City Paper.

That same year (2010), the Bozzuto Group, a privately held real estate company, broke ground on a mixed-use development project, a block away from Dahlgreen. The new project was so close to the Rhode Island Avenue station that you could hear garbled announcements about train delays over the loud speaker.

A few years later, just as the Bozzuto Group started leasing at Rhode Island Row, offering amenities like a resort-style outdoor pool, state-of-the-art fitness center and electric car-charging stations, Mission First was marching their tenants back into units that didn’t even have heat or air conditioning.

The lack of basic amenities weren’t the only problems Dahlgreen tenants encountered.

“After the renovations in 2012, we moved back in and then, six months later, we saw water damage in the living room,” Lightfoot said. “The walls, carpet and floors had mold.”

Leon Lightfoot, who has lived in Dahlgreen Courts Apartments with his family since 1999, stands in front of the building. Lightfoot said that his wife and son have asthma and that he has headaches and other respiratory problems. (Freddie Allen/AMG/NNPA)

Donta Waters, a six-year resident of Dahlgreen Courts and the current president of the tenants’ association, said that Mission First took a “bath-fitters approach” to the renovations—masking serious structural problems with dry wall and fresh paint. Waters said that he didn’t understand why Mission First moved tenants back into their apartments, as the building renovations continued.

“Many of us moved back into our units and found dust and debris everywhere, that we had to clean,” Waters said. “They were still actively doing construction, so we couldn’t even move back in through the front door. We had to move in through the back.”

Trudging through plastic drop cloths and duct tape as contractors worked with masks on, Waters and other residents expressed concerns about lead exposure. The Dahlgreen buildings are nearly 100 years-old and the federal government didn’t ban the consumer use of lead-based paint until 1978. Renovating older buildings can present potential health hazards from toxic lead dust.

Brian Gormley, a veteran real estate lawyer representing the Dahlgreen residents in the civil suit, said, “If you can’t live in a place safely without being exposed to contaminants that adversely affect your health…that’s beyond incompetence and beyond negligence.”

According to court documents, at least 40 tenants have “tested positive for elevated levels of lead in their blood and/or Chronic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (“CIRS”) as a result of exposure to lead, mold and other biotoxins, due to negligence and other breaches of Defendants’ duties to maintain habitable housing conditions.”

Although the science around CIRS is murky, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), a federal agency tasked with safeguarding the health of American citizens, supports findings that link indoor exposure to mold to upper respiratory tract symptoms, like coughing, and wheezing in otherwise healthy people; with asthma symptoms in people with asthma; and with hypersensitivity pneumonitis.

Chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis may present with a myriad of flu-like symptoms including fevers, chills, muscle and joint pains, headaches, chronic bronchitis, shortness of breath, anorexia, weight loss, and fatigue, according to the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute.

Other studies suggest a link between early mold exposure to the development of asthma in some children, particularly among children who may be genetically susceptible to asthma development.

“We still have problems with water and mold. I’m very concerned for my wife and my son. I have headaches, respiratory problems and now I have to use an inhaler,” Lightfoot said. “My wife and son have asthma. I’m so pissed off that my wife and son have to endure this.”

Waters said that if the Mission First developers had taken their time to properly make the renovations to the buildings, the tenants’ health wouldn’t have been compromised.

“We have children, we have seniors,” Waters lamented. “It’s a shame how they have treated us.”

For months, raw sewage backed up from the property manager’s office into the common areas; Dahlgreen residents were forced to tip-toe through human waste to check their mailboxes and to pay their rent.

“The smell was horrendous. It was almost like a decomposing body,” Waters said. “You could see the raw sewage in the hallway, as soon as you walked into the building.”

(Freddie Allen/AMG/NNPA)

Waters said that the entire ordeal is depressing and that his tenure as president of the Dahlgreen tenants’ association has been challenging, as small groups of residents gather in his apartment, almost daily, to voice their frustrations.

Gormley agreed with Waters that Mission First rushed the repairs on the units, which had a negative impact on the health of some of the residents.

Gormley, who has represented property owners and tenants in these types of disputes, said that Mission First didn’t get a certificate of occupancy for the renovated Dahlgreen apartments—a government-issued document that certifies that a building is safe and liveable—until three years after they moved the tenants back into their units.

The Washington, D.C. lawyer added that the Dahlgreen Courts case is a symptom of the affordable housing crisis in Washington, D.C. and the city’s lax enforcement of housing regulations already on the books.

It’s important to remember that Mission First Housing Group isn’t some mom and pop nonprofit organization. According to its website, Mission First began 25 years ago as “as a joint venture between the City of Philadelphia, HUD and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.” The company acquires properties and leverages funding through “complex financing sources.” Now the company manages more than 3,300 units, providing housing for roughly 4,000 residents in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia and Washington, D.C.

“You can’t tell me that [Mission First] doesn’t know what they’re doing,” Brian Gormley said. “You can’t tell me that.”

The company’s website also states that the group’s mission is, “to develop and manage affordable, safe and sustainable homes for people in need, with a focus on the vulnerable.”

Some Dahlgreen tenants and housing advocates believe that the company’s targeting of vulnerable populations is intentional.

“We’re in an area characterized as ‘low-income,’ but you need to treat me the same as you [treat] people who live in Georgetown,” Lightfoot said.

The Dahlgreen lawsuit claims that Mission First reduced services to residents, referred tenants to third-party vendors to repair laundry services and blocked access to the Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs website in the Dahlgreen’s business center. The lawsuit also says that Mission First changed the locks to the community room right before a scheduled tenant association meeting.

Tenant harassment as a tactic to displace low-income residents from rent-controlled units is nothing new or even unique to Washington, D.C.’s housing market.

Just look at New York City.

“Initially seen mostly in the East Village and the Lower East Side, the tactic has spread with gentrification to places like Crown Heights, Bushwick, Washington Heights, and other working-class neighborhoods with good housing stock and decent public transportation,” The Village Voice reported.

Victor Bach, a senior housing policy analyst in New York City told The Voice that, “if you sue ten tenants for nonsense, you can get four to relinquish their rights.”

And if those tenants that give up their rights live in rent-controlled units, that could mean an increase in revenue for the developer.

Now, one-bedroom units at Dahlgreen Courts Apartments start at $1,044, according to www.rentcafe.com, twice the monthly rent that “Grandfathered” tenants are paying now. One-bedroom units at Rhode Island Row start at $2,112, according to the Bozzuto Group’s website.

The Dahlgreen Courts towers sit in a vortex of steady and far-reaching changes brought about by gentrification.

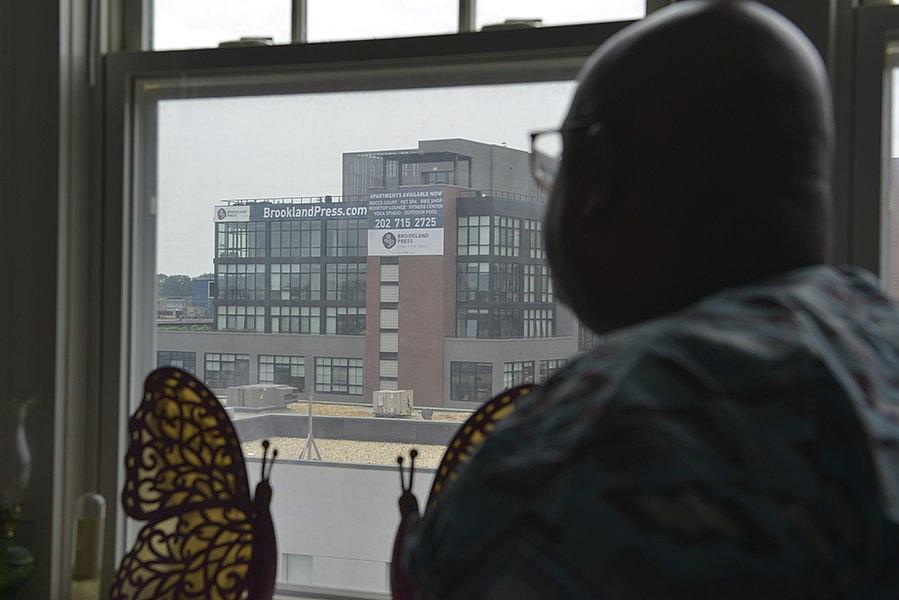

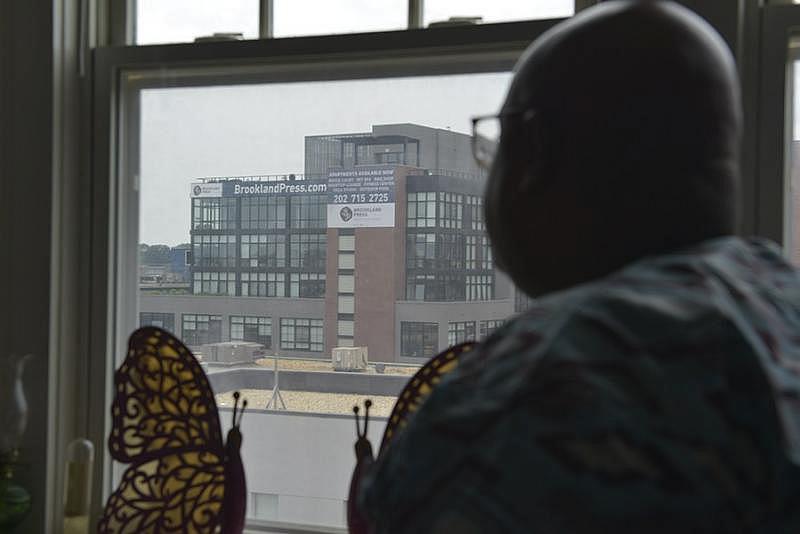

From his living room window, Waters can see another luxury apartment building named Brookland Press, a stone’s throw from the metro station, at 806 Channing Place in Northeast.

Donta Waters, the president of the tenants’ association, can see Brookland Press from his living room window. (Freddie Allen/AMG/NNPA)

Where Dahlgreen crows about bedroom carpet, stoves and ovens as amenities, Brookland Press offers a yoga studio, a game room, a dog run, a pet spa and 24-hour concierge services. One-bedroom apartments at Brookland Press start at $1,876/month.

Yasmina Mrabet, an affordable housing advocate who is working with the Dahlgreen tenants’ association, said that the housing market in the District is out of control and that city officials aren’t doing enough to address the crisis.

“Many of these properties have the only affordable housing options available to poor and working-class people,” Mrabet said. “We have plenty of resources to solve the housing crisis right now. The issue is that the city is choosing to put money into soccer stadiums, basketball practice facilities, and luxury redevelopments, instead of into quality, affordable housing.”

One in five D.C. households now pay more than half of their income towards rent.

For families with low and moderate incomes, this means that they have little left over each month for other basic necessities like clothing, transportation and food. It also makes them more likely to be one job loss or illness away from homelessness.

“They’re trying to force us out and they think we don’t have the knowledge of what to do,” Lightfoot said. “What’s frustrating to us is that things are getting more expensive. Where in Washington, D.C. do they want us to go? Gentrification is not for us.”

Gormley said that it’s important that renters persevere and organize when their confronted with challenges that are similar to what the Dalgreen residents are living through.

“Get in touch with your tenants’ association and other grassroots organizers,” Gormely said. “If you can work with other people, you have power in numbers.”

Waters said that renters who live in Washington, D.C. and other major metropolitan areas should ask as many questions as they can and take the initiative to do their own research and learn about their rights as tenants.

“If you rely on the property managers, especially when you’re dealing with low-income residents, some of them could try to take advantage,” Waters said.

[This story was originally published by Black Press USA]