San Bernardino County: Jails critically lack health care, but have plan to improve

This story was produced as part of a larger project led by Nikie Johnson, a participant in the USC Center for Health Journalism's 2018 Data Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

Riverside County: Jails rebound from shocking lack of resources

Southern California jails are trying to improve health care. But inmates are dying

Los Angeles County: World’s largest jail system getting a health care overhaul

Orange County: Jail health care called inadequate, but some changes underway

How Southern California jails are changing the way they treat the mentally ill

Riverside County jails unfair – and perhaps cruel – to some inmates, grand jury says

Riverside County jail inmates hope hunger strike will lead to policy changes

Women in Riverside County jail stage 16-day hunger strike over their treatment

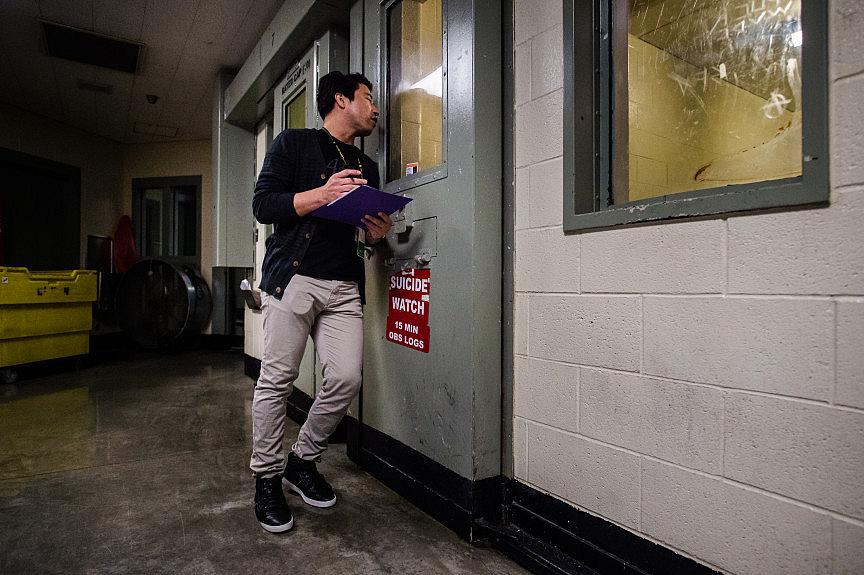

Clinician Marvin Rodriguez checks on an inmate in a suicide-watch cell at West Valley Detention Center in Rancho Cucamonga on Friday, June 21, 2019.

(Photo by Watchara Phomicinda, The Press-Enterprise/SCNG)

The unkempt man stood at the window of a stark cell with a red sign on its thick metal door: “SUICIDE WATCH.”

“Are you having thoughts right now about hurting yourself?” clinician Marvin Rodriguez asked from the hallway outside, leaning up against the window as he spoke and made notes on a clipboard. “Do you have a plan?”

If he had a plan, that means he’d been thinking about it and the situation is more serious. The inmate said yes. Rodriguez asked why.

“Because I’m in jail!”

“You can be free,” Rodriguez said encouragingly. “There’s things you can do.”

Their conversation took place one June afternoon in the intake area at West Valley Detention Center, the largest of San Bernardino County’s four jails. The window of one holding cell looked stained – an illustration of an unpleasant truth of jails, that severely mentally ill inmates sometimes wipe feces and spray urine on their walls.

Making improvements to the intake area – and to the overall services available to mentally ill inmates – are among the steps that the department has been taking since it was sued in 2016 by the Prison Law Office, which alleged that San Bernardino County jails were violating the constitutional rights of its almost 6,000 inmates.

Nurse Sheila Witherspoon checks on inmates as they receive dialysis treatment in a clinic at West Valley Detention Center in Rancho Cucamonga on Friday, June 21, 2019. (Photo by Watchara Phomicinda, The Press-Enterprise/SCNG)

“Jail medical, mental health, and dental care is so deficient that it is harming the people it aims to serve,” the suit contended. “Jail staff uses excessive force against people they are charged with protecting, and fails to take even the most basic steps to prevent violence. Jail staff discriminates against people with disabilities by locking them in housing units that don’t have accessible toilets and showers, and by locking people with mental health problems in tiny cells for 22 to 24 hours a day, which only worsens their psychiatric conditions.”

The Sheriff’s Department quickly agreed to cooperate and come to a settlement in the federal class-action lawsuit, perhaps learning from the experience of its neighbor to the south; Riverside County had been sued for similar issues by the Prison Law Office in 2013.

The settlement with San Bernardino County was finalized in December 2018. Under an agreement known as a consent decree, the county is required to improve its medical, mental health and dental care, and adopt new policies on use of force and the Americans with Disabilities Act. The jails will undergo monitoring by four experts until they’ve been in compliance with the terms for a year.

The federal court agreed with the county to let the experts’ initial assessments be filed under seal, meaning they aren’t public, unlike in Riverside County. The experts’ follow-up reports every six months aren’t public in either county.

Care still critically lacking

The first six-month progress report was turned in this spring, said Don Spector, executive director of the Prison Law Office. They didn’t contain the good news that he thought the county was expecting.

“They have a critical lack of mental health and medical staff, and a lot of elements of the remedial plan are not being met because of that,” Specter said.

He said the county has made some changes in mental health care and started some programs for the sickest of inmates, but it’s “not nearly enough.”

“There are many, many who still don’t get any treatment – any meaningful treatment,” he said. “People go by and check on them but they don’t get the help they need. They have psychotic people in cells who aren’t getting treatment. It’s a lot of people.”

The two sides met to discuss the reports, and Specter said sheriff’s officials promised they’d take “serious and sustained measures. We’ll see.”

Speaking about a month afterward, Jerry Gutierrez, executive officer for the San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department, said they had already started working on evaluating staffing needs and workflow.

“We’re going to get there,” he said. But he had a quick answer for what the biggest challenges would be: “Space. Infrastructure. Recruitment.”

‘Building an airplane in mid-air’

Sheriff’s officials were eager to show off the improvements they’ve made so far, and to try to share an understanding of the challenges they face. They’re tasked with making drastic changes in a jail system that was designed in a different era.

Inmates now have more mental health, substance abuse and chronic health problems, officials say, and some are staying in custody longer due to a state law passed in 2011 that began sending some convicted felons to county jails rather than state prisons.

“Capacity – that’s what’s really wrong here,” Undersheriff Shannon Dicus said. “We’re not pushing back, but I always tell people, what we’re doing is like building an airplane in mid-air.”

Even before it was sued, the Sheriff’s Department had been getting creative to deal with the increasing need for health care. For example, a hallway at West Valley’s medical ward got turned into a dialysis clinic that now provides about 1,400 treatments a year.

One of the first areas tackled under the lawsuit was intake. The health screening is now twice as long and always administered by a nurse, not a deputy.

The goal for anyone who was already on medication is for them not to miss a dose, said Terry Fillman, the sheriff’s health services administrator. Anyone with a mental illness will talk to a clinician much faster than before, he said.

The mental health housing units are now guarded by deputies who volunteered to be there and receive special training.

Not all of the changes mandated by the settlement have gone smoothly. Severely mentally ill inmates on lockdown are now required to have three hours a week of recreation time. More time out may benefit their mental health, Deputy Chief Sam Fisk said, but it leads to more interaction – and more violence – between them, meaning more guards have to be present.

Stepdown success

A visit to West Valley in November showed how a new stepdown process is working, in which severely mentally ill inmates can graduate to a less restrictive dorm-style housing area or even the general population if they improve enough.

In some of the rooms, there were four inmates, wrists handcuffed and legs shackled, sitting at far corners of two tables as a clinician talked to them.

In another room, two teams of men were competing against each other in the sort of challenge kids might get in school to improve creative thinking and build trust. They had to use string, not their hands, to pick up plastic cups and stack them into the tallest tower they could.

The men laughed and got engaged, and when time was called, the winning team cheered and pumped their fists.

Not everyone was participating. It wasn’t required. Some men stayed back in their bunk beds or leaned against the second-story railing to watch. But one of those observers eventually decided to join in.

Success, Fillman said.

[This story was originally published by The Sun.]