San Diego Hospitals Challenged by Jump in ER Use

This story is part of a larger project for the Center for Health Journalism's 2018 Data Fellowship, a program of USC Annenberg.

Other stories in his fellowship project include:

Part 1: Bottleneck in Psych Care Leaves Hospitals, Patients in the Lurch

Part 2: EDs Deal With Shortfalls In Mental Health Care

Part 3: Hospitals Try to Balance Care, Financial Constraints

A sign points the way to the emergency room at Palomar Medical Center Escondido.

Photo by Jamie Scott Lytle

In 2013, Scripps Mercy Hospital’s emergency department doubled in size after a multiphase revamp. Six years later, Scripps officials said demand caught up.

“It’s kind of like if you build it, they will come,” said Dr. Valerie Norton, the department’s medical director, upon stepping into the ER. “They came.”

San Diego’s major hospital systems — Scripps Health, Sharp HealthCare, UC San Diego Health, Palomar Health and Tri-City Healthcare — saw a crush of ER patients in recent years. Challenges run from the financial to the operational.

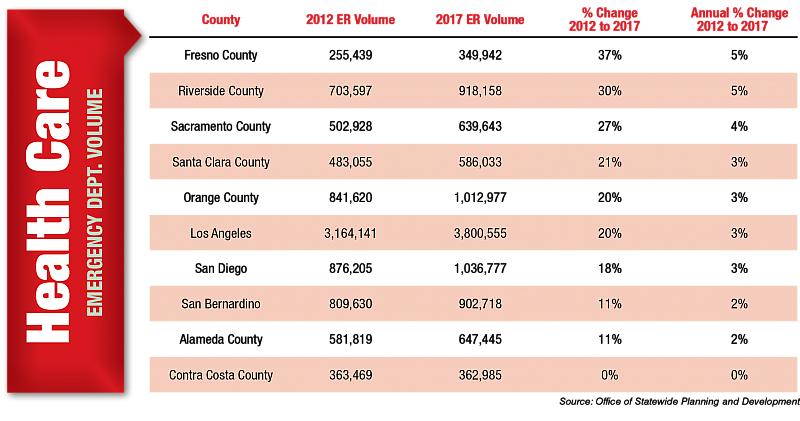

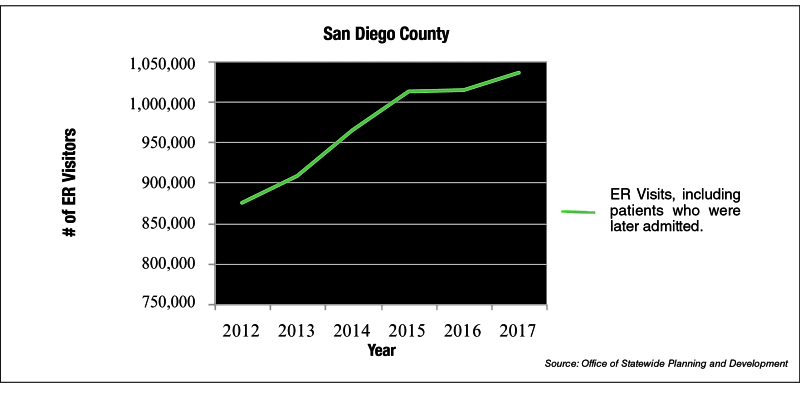

Countywide, ER visits, including emergency patients who were later admitted, jumped 18% from 2012 to 2017. Visits went from 876,000 to 1.036 million during the span, an average 3% growth rate.

That’s according to a San Diego Business Journal analysis of data from California’s Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, or OSHPD.

Driving the trend: an explosion in Medi-Cal enrollment and difficulties for the newly insured in accessing primary care. The 18% gain was about three and a half times greater than San Diego’s population increase during the period.

In response, hospitals added emergency beds and staffing. Some opened emergency units tailored to mental health patients. On the demand side, they steer some cases to facilities with lower overhead.

State data gives an incomplete picture of how San Diego hospitals were financially impacted by more ER encounters.

Scripps CEO Chris Van Gorder said in the past ER visitors were often a financial plus, but no longer with a shift to “valued-based” payment models that reward or penalize hospitals based on performance. Metrics include ER readmissions.

“We can no longer say it’s a thumbs up when our emergency departments are busy,” Van Gorder said.

In addition, ERs are an expensive care venue, demanding extensive medical equipment and a range of on-call specialists. That’s why Scripps and other hospitals have boosted investment in outpatient sites, as well as urgent care and walk-in clinics, geared toward less severe conditions.

Patients can call a Scripps triage line to gauge a fitting venue of care, among other efforts to promote ER alternatives.

“Many of us need emergency care, but there’s a lot of us that can be taken care of in urgent care centers or day clinics,” Van Gorder said.

Another piece of the puzzle: primary care. It took on greater importance after the Affordable Care Act in 2014 expanded Medi-Cal for low-income Californians. Some of the newly insured, including homeless people, didn’t have a regular doctor and turned to ERs for care.

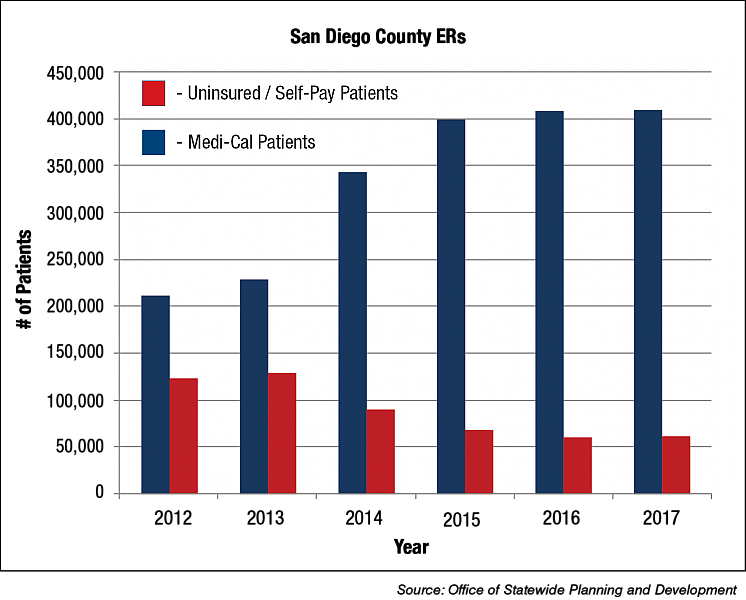

In San Diego in 2017, Medi-Cal patients accounted for about 39% of ER visits, up from about one-quarter in 2012.

On the flip side, with more on Medi-Cal rolls, those without insurance made up 6% of ER encounters in 2017, down from 14.1% in 2012.

Kip Piper said the greater number of ER Medi-Cal patients poses a challenge for hospitals. He’s a health care consultant and former senior adviser to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, or CMS.

Hospitals receive low reimbursement for this population — and some Medi-Cal patients require additional resources. Under a new California law, hospitals must take extra steps when discharging homeless patients, a response to horror stories of patients being dumped on streets after treatment.

“Even if everything goes perfectly with the patient’s care, the hospital knows the discharge can be tough,” Piper said.

Lack of Primary Care Access

More Medi-Cal patients in ERs run counter to a tenet of the Affordable Care Act. The law was designed to decrease ER visits through bolstered insurance coverage.

But there haven’t been enough primary care doctors and specialists to handle the increased Medi-Cal population, said Greg Knoll, CEO of the Legal Aid Society of San Diego.

In 2015, only 60% of San Diego primary care physicians accepted Medi-Cal, below a statewide average of 65%, according to a 2017 California Health Care Foundation report. Low reimbursement is the main reason.

Knoll said factor in needlessly complicated health plans, combined with the fact that Medi-Cal patients largely don’t pay for expensive emergency care, and it doesn’t come as a surprise that they rely on ERs for care.

“Enough time isn’t taken to show people who haven’t had health coverage for a long time how to use their insurance,” Knoll said.

But as a sign health systems are absorbing the insurance expansion, Medi-Cal numbers in ERs have leveled off after years of growth.

San Diego hospitals are far from alone in a crush of emergency patients. From 2012 to 2017, six other major California counties saw larger percentage increases.

Fresno logged the biggest jump in ER visits, up 37%. Riverside ranked second with a 30% increase, followed by Sacramento with a 27% rise.

Amid higher ER volumes in San Diego, median wait times appeared to rise at most hospitals.

Comparing 2017 to four years prior, patient waits increased at eight of 13 hospitals, according to CMS survey data on how long patients wait to be seen. Data for two hospitals weren’t available.

The biggest swing came at Sharp Chula Vista Medical Center. The median wait was 100 minutes from January 2013 to March of the following year. In 2017, the median wait fell to 44 minutes, which still ranked comparatively high.

Sharp HealthCare, which operates four ERs, has added beds and staffing to ease ER waits. And last year, the health system opened a clinic next to its Grossmont hospital for patients who need urgent medical attention but not an ER.

Dan Gross, executive vice president of hospital operations at Sharp, said it’s also about throughput. That is, moving patients through emergency care stages faster.

Sharp has leaned on data to do so — notably, a hospital command center identifies open beds.

“I can then get to patients quicker on the front end,” said Gross.

On the back end, Sharp is also working on an artificial intelligence model that flags patients most likely to be readmitted, based on 18 characteristics, like number of emergency room visits and relationship status. After discharge, Sharp would check on their health and offer support.

A mental health crisis, health officials say, has complicated ER care.

San Diego saw 38,170 mental health visits to ERs in 2017, according to OSPHD. In the last couple years, some with mental health needs gained Medi-Cal, fueling the ER jump, according to hospital representatives.

Meanwhile, there’s a shortage of psychiatric inpatient and continuing care beds, increasing the likelihood patients will cycle through the system, as detailed in a three-part San Diego Business Journal series in April.

Most emergency rooms are tailored to physical ailments, with some rethinking the model.

In recent years Palomar Health and Rady Children’s Hospital each opened a crisis stabilization unit for short-term care of psychiatric emergencies. At Palomar, a new crisis unit with 16 beds — more than double the current size — will open this summer.

“It takes some pressure off the ER,” said Sheila Brown, chief operations officer of Palomar Health.

Palomar has also partnered with federal community clinics, which provide medical and dental care to low-income residents. They’ve done the heavy lifting of the Medi-Cal expansion.

With greater Medi-Cal numbers, North County Health Centers opened two additional facilities to bring its total to a dozen clinics. It decided where to expand after combing through granular data — like demographics, socioeconomic and travel patterns.

“If more and more patients are coming to us from ZIP codes farther and farther away, that maybe shows an opportunity to locate a clinic closer to where they are,” said Barbara Kennedy, CEO of North County Health Services.

Which age group uses San Diego ERs the most? In 2017, ages 20-29 represented the largest slice of ER volumes, at 14% or 148,028 visits.

But more seniors are showing up at ERs, a sign of a “silver tsunami” that will reshape health care in the coming years.

In San Diego, ER visits among ages 60 to 69 shot up 43% from 2012 to 2017, the biggest increase among the age brackets. Ages 70-79 came in second, with a 34% jump.

With the population aging, UC San Diego Health earlier this year opened a senior ED, complete with specially-trained physicians and senior-tailored architecture.

It features calibrated lighting, sound-absorbing walls and contrasting colors between walls and floors to reduce fall risk. Upon arrival seniors undergo screenings for mobility, fall risk and cognition.

Early data indicates these exams are reducing readmissions, according to Dr. Ted Chan, chair of UC San Diego’s emergency medicine department. The health system has care in mind, along with the bottom line.

“Increasingly, insurers and the federal government are looking for payment programs where they reward not just what you do, but the quality of what you do,” Chan said.

The ED, called the Gary and Mary West Emergency Department, was the first in California to receive a special designation for geriatric emergency care, awarded by the American College of Emergency Physicians.

Kaiser Permanente San Diego, Rady Children’s Hospital and Tri-City Medical Center did not respond to interview requests.

Inside Scripps Mercy

It’s 2:30 p.m. on a Friday at Scripps Mercy Hospital. The emergency waiting room is largely unoccupied. Stepping inside, the same goes for hallway beds with makeshift blue curtains.

These beds allow treatment to get started while patients wait for more exhaustive care.

The lull likely won’t last, said Norton, medical director of the department, which is divided into six stations catering to different care levels. At the stations, nurses sit at semi-circle tables, ready to spring into action.

Scripps Mercy’s ER is the busiest in the region. In 2017, it saw 120,000 visits, including those that resulted in admissions. Norton said an ER expansion, finished in 2013, relieved cramped conditions, but the department’s 54 beds now aren’t enough. But ER efficiency isn't just about the number of beds.

Taking aim at wait times, Norton said the department has staffed up — and quickened discharges. That’s included increasing the number of non-hospital beds patients can discharge to — Scripps leases beds at nursing homes, for instance.

In the ER waiting room, Scripps workers said they were bracing for the late afternoon rush.

This article was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s Data Fellowship and published originally in the San Diego Business Journal.