‘A shining moment’: Congress agrees to restore Medicaid for Pacific Islanders

This story was reported by Dan Diamond with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism's 2020 National Fellowship and the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism.

Other works in this series include:

How 100,000 Marshall Islanders Got Their Health Care Back

Irradiated, Cheated and Now Infected: America’s Marshall Islanders Confront a Covid-19 Disaster

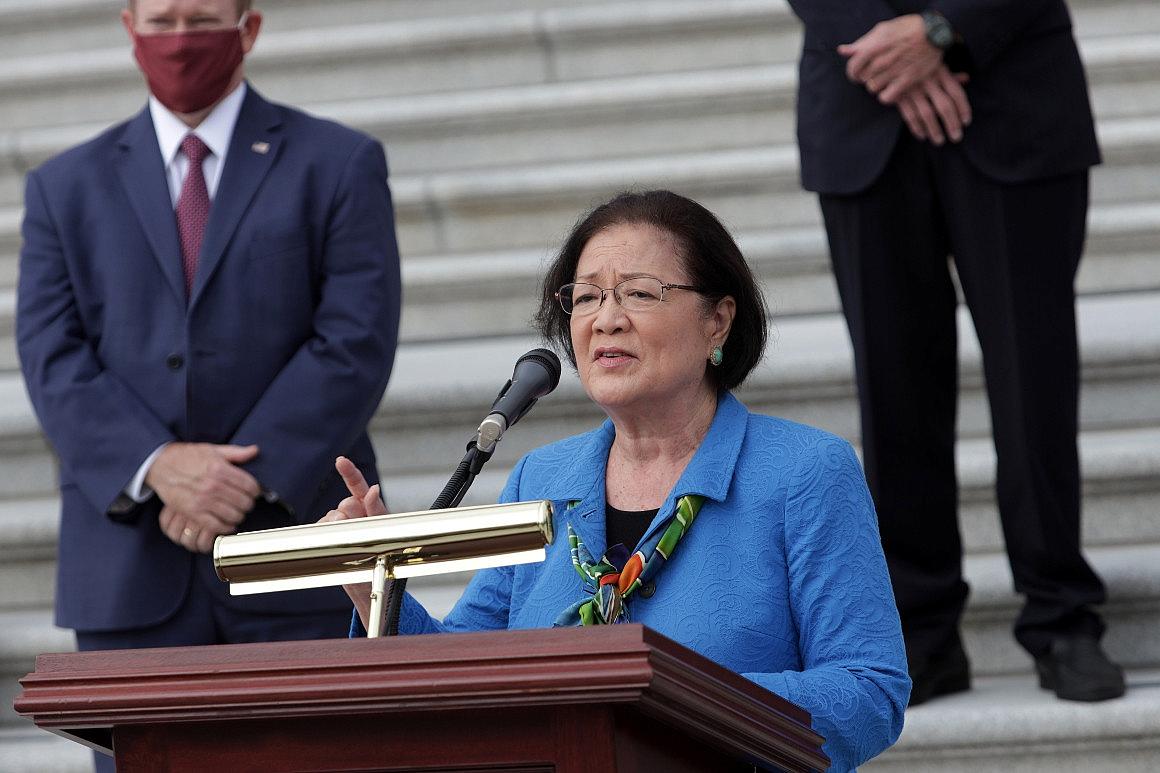

Democratic lawmakers like Sen. Mazie Hirono and her Hawaii colleagues had spent about two decades trying to restore Marshall Islanders' health benefits.

Alex Wong/Getty Imag

The wait may be over for tens of thousands of Marshall Islanders after nearly 25 years of seeking to correct an oversight that denied them federal health benefits.

Congressional negotiators on Sunday agreed to allow Marshallese living in the United States to sign up for Medicaid, revising a drafting mistake in the 1996 welfare reform bill that barred the islanders from the program, according to three people with knowledge of the deal.

Democratic lawmakers like Sen. Mazie Hirono and her Hawaii colleagues had spent about two decades trying to restore the islanders’ coverage — saying that the United States broke its promise to the Marshallese after using their homeland to test dozens of nuclear bombs — but legislative proposals repeatedly died without Republican support. This spring, the House passed a bill to restore the islanders’ Medicaid for the first time in more than 20 attempts, although it stalled in the Senate.

The decision to bar the Marshallese from Medicaid has contributed to the islanders’ greater rates of sickness and death, researchers have concluded, and those disparities were accelerated by this year’s Covid-19 pandemic, which has ravaged the Marshallese community in the United States.

Sunday night’s deal was included in the larger coronavirus relief and year-end funding package that lawmakers also finalized on Sunday. That package still needs to be voted on by both chambers of Congress.

Spokespeople for Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi confirmed that the package included the Medicaid fix, which has been estimated to cost about $600 million over a decade.

The deal would apply to islanders covered by the Compact of Free Association, or COFA, which covers citizens of the Marshall Islands, Palau and Micronesia. It was hammered out between the Pacific island nations and the United States in the decades after the U.S. military used the Marshall Islands as a testing site for dozens of nuclear bombs in the 1940s and 1950s. As part of the 1980s-era compact, the islanders were allowed special rights to resettle in the United States — and promised access to Medicaid.

However, POLITICO in January detailed how the Marshallese and other islanders lost access to Medicaid as part of a 1996 welfare reform package that barred them from signing up for the low-cost health program. While policy analysts have called it a legislative drafting mistake, the policy contributed to high rates of uninsurance, poor health outcomes and chronic disease that went untreated.

The islanders also have been disproportionately affected by this year's Covid-19 pandemic, POLITICO reported last week. A team of researchers for the Centers for Disease Control found this summer that one Arkansas community of Marshallese was more than 60 times likely to be hospitalized and die from Covid-19 than their white counterparts.

Hirono, who worked with colleagues including Sen. Brian Schatz (D-Hawaii) and Rep. Tony Cárdenas (D-Calif) to build legislative consensus to restore Medicaid for the islanders, framed the deal as the United States “upholding its promises” to the island nations.

“Restoring Medicaid access for COFA citizens has been one of my top priorities since arriving in the Senate in 2013,” the Hawaii senator said in a statement. “This work has become only more urgent as the COFA community in Hawaii and across the country have experienced overwhelming levels of disease and death from COVID-19.”

Juliet Choi, CEO of the Asian & Pacific Islander American Health Forum, hailed the agreement as “a shining moment where Congress’ commitment to do the right thing will now finally allow thousands of COFA families gain access to Medicaid again."

The Government Accountability Office this summer estimated that about 94,000 Marshallese and other islanders covered by COFA lived in the United States as of 2018. Many of the Marshallese came to the United States in middle age, having fled their radiation-scarred homeland, taking jobs as factory workers and housekeepers, where they didn’t receive health benefits. Some surveys found that 50 percent or more of the islanders were uninsured, leading them to put off necessary health care.

The Marshallese also disproportionately suffer from conditions like diabetes and hypertension, leaving them vulnerable to serious Covid-19 complications this year.

Reached on Sunday night, several islanders expressed relief about Congress' deal.

"I'm overwhelmed by this," said Maitha Jolet, a 62-year-old Marshallese man living in Dubuque, Iowa, who's worked to help uninsured Marshallese community members deal with their high health care bills. "We've been waiting for this for 25 years. It's something I never thought would happen."

[This story was originally published by Politico.]