Teens increasingly turn to Safe2Tell for suicide, mental health emergencies. But Colorado doesn’t track what happens next.

This story was produced as part of a larger project led by Jessica Seaman, a participant in the 2019 National Fellowship, a program of USC Annenberg's Center for Health Journalism.

Her other stories in this series include:

Youth suicide rates during the pandemic foreshadow what experts say will be a “tsunami of need”

What Colorado can learn from a neighboring state’s new approach to stopping youth suicide

Jennifer, left, and her daughter Elizabeth, right, are pictured in their backyard on Feb. 23, 2020. Police were dispatched twice to check Elizabeth for self-inflicted cuts following Safe2Tell reports.

Helen H. Richardson, The Denver Post

Jessica Seaman reported this story with support from the Fund for Journalism on Child Well-Being, a program of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

You can find out more about how The Denver Post follows guidelines for reporting on suicide here.

See more of the Crisis Point project here.

**

The first time police came for her daughter, Jennifer had just finished a shower.

Dressed in a robe and with her soaked hair wrapped in a towel, she greeted the officers who arrived at her Denver home in search of 13-year-old Elizabeth.

On that same Saturday, a second set of officers pulled up to her former husband’s home in a neighboring county. They, too, were looking for the teenager.

Upset after a breakup, Elizabeth — her middle name — had found a photo on social media that showed an arm with cuts on it, and sent it to a friend the night before. Someone with that friend, alarmed by the image, did what students across Colorado are told to do in such situations: They notified Safe2Tell.

“I thought she broke the law,” said Jennifer, who agreed to speak to The Denver Post on the condition only her first name be used to protect her daughter. “I mean, when police come to your door that’s kind of the natural response, right?”

Instead, the officers had come that morning in 2016 to search Elizabeth for self-inflicted cuts.

After finding her at home in Denver, police separated the mother and daughter into different rooms, then asked Elizabeth to roll up her sleeves.

* * *

Colorado students have increasingly turned to the anonymous reporting program Safe2Tell to seek mental health help for themselves and their peers, especially since 2014, when suicide became the leading cause of death for young people in the state.

But Safe2Tell was never designed to operate as a crisis line, and The Denver Post found that a lack of data collection and a state law restricting the release of information mean there’s little public accountability about what happens after authorities respond to tips.

The program, now run out of the Colorado Attorney General’s Office, was created more than two decades ago to combat youth violence. In the aftermath of the 1999 Columbine High School shooting it became a crucial part of the state’s efforts to prevent another such attack.

//

Now, though, reports of children and teens at risk of harming themselves — rather than others — make up the largest share of Safe2Tell’s tips. Interviews with parents, current and former students, and state and local officials reveal that while students have changed how they use Safe2Tell, the program is still deeply rooted in law enforcement.

As a result, when someone makes a suicide or mental health report, police are among the first notified — and often the ones responding to medical crises. That can be traumatizing to young people, especially when they are struggling with their mental health

“The overall issue is that we want to make sure there is an appropriate response depending on what the need of the caller is — and there’s no way to know that right now,” said Sarah Davidon, a Denver-area mental health policy consultant.

The attorney general’s office is unable to say how often law enforcement officers — as opposed to school staff or medical professionals — respond to suicide and mental health reports made through Safe2Tell, because it doesn’t track that data.

“What we know is that the tips we get are followed up on,” Attorney General Phil Weiser said. “What is unknowable is did the follow-up end up saving someone’s life or not. We know that it has constituted an intervention that has the potential of being life-saving.”

He added, “I’m comfortable saying that we are saving people’s lives because we’re hearing from parents: ‘My kid’s getting the help they need because of Safe2Tell.’”

State officials said the program is required by law to notify schools and law enforcement when it receives a report. It’s up to local officials to decide who responds to a Safe2Tell tip and the program doesn’t always know who ultimately acts on it, said Lawrence Pacheco, spokesman for the attorney general’s office.

State officials stressed that Safe2Tell is a “conduit” that connects children and teens with the resources available in their community.

“This is not a Safe2Tell issue,” Weiser said of law enforcement responding to mental health crises. “There’s clearly a greater need for services than we are providing.”

* * *

Apryl Alexander, an associate professor of psychology at the University of Denver, poses for a portrait on Thursday, Sept. 3, 2020. “We have to think about people’s perception of police, whether it’s children, kids of color. So having a police officer come to your door when you’re already experiencing a crisis just elevates your system.” AAron Ontiveroz, The Denver Post

Families and mental health experts argue Safe2Tell’s reliance on law enforcement traumatizes teenagers, particularly those of color, and can prevent them from seeking help in the future.

They said even when someone finds help, the presence of police during these situations appears to punish children and teens for mental health issues, which already are heavily stigmatized.

“It criminalizes it for them and sort of confirms that what they feel is wrong,” said Michelle Simmons, a licensed professional counselor in the metro area.

And, in some cases, law enforcement intervention from suicide or mental health reports to Safe2Tell can result in a child handcuffed in the back of a police car, according to accounts from former and current students.

“I remember after the Safe2Tell experience, I really shut down and was like, ‘I’m not going to talk to anyone else about my mental health issues because I don’t want to go through that again,’” said Melanie, a former student who spoke on the condition that her last name not be published. “It’s terrifying for any high schoolers to have, like, police officers in full uniforms with guns on their belt come to your door and talk to you about, like, your sadness.”

The role of law enforcement, including in schools, has come under scrutiny in recent months following protests against police brutality and a national reckoning about systemic racism.

“We have to think about people’s perceptions of police, whether it’s children, kids of color,” said Apryl Alexander, an associate professor in the University of Denver’s Graduate School of Professional Psychology. “So having a police officer come to your door when you’re already experiencing a crisis just elevates your system.”

Mental health experts said that data on what type of help was offered in response to Safe2Tell tips — such as whether families were referred to counseling or how often police placed children on 72-hour holds — would help officials know if mental health care was ultimately provided to a child. Such data could also inform decisions on how money is directed to mental health services for youths, they said.

“I would love to know what that response process would look like,” Alexander said. “I want to know if there was a lack of intervention at a certain point and youth didn’t get the care that they needed.

“What we can say is that Safe2Tell is working when people are worried,” she said of the program’s initial response. “Then what?”

* * *

The 2014 Colorado law that placed Safe2Tell under the attorney general’s office also makes any information not in the program’s annual report confidential, including making it a crime for the program or others to release records on what happens when authorities act on a report, according to state officials.

“We want to make sure that we are truly protecting the confidentiality (of students) so we may be a little more conservative on what we feel is appropriate to release to the public,” said Safe2Tell Director Essi Ellis.

In an effort to reconstruct the path of Safe2Tell reports, The Post filed more than 100 public records requests with school districts in the Denver metro area and police departments across the state.

The responses varied greatly. Some agencies did not have data on what happened after they responded to a Safe2Tell report. Other local officials declined to release any data or provided incomplete information based on their interpretation of the state law. A small number of agencies and districts — potentially violating the law — released full Safe2Tell response data, including when 72-hour holds were implemented.

“What we don’t know then is the effectiveness of the program and the deterrence,” Simmons said. “Is there a deterrence because police are going to come and I don’t ever want to get in trouble? And is it a good use of public safety funds?”

(Simmons works with Centura Health’s mobile crisis unit and helped The Post facilitate a community discussion on youth suicide in 2019. Centura is a sponsor of The Post’s Crisis Point project.)

In 2018, Safe2Tell received money to hire a data analyst because the program was aware it could improve how it measures its effectiveness, including further follow-up with local officials on how they acted on a report, said Susan Payne, the founder and former head of Safe2Tell.

“We knew this was a gap then,” she said.

Before the pandemic, Weiser said Safe2Tell did not have enough money in its budget, which was just over $855,000 during fiscal 2018-19, to monitor what type of help is offered to students. It would be “pretty burdensome” for his office to mandate schools and police compile the information, he said.

Now, significant changes to the program seem even less likely as the Department of Law’s budget saw a 25% cut in general fund dollars as the financial fallout from COVID-19 forced officials to make sweeping cuts to the state’s budget. For Safe2Tell this resulted in a reduction of $56,000 and one full-time position.

“I’m concerned about continuing to do well what we have been doing, and building and expanding is on the back burner,” Weiser said.“We’re going to have to really think long and hard before expansions given the cutbacks that we’ve had.”

Safe2Tell is expected to release a new annual report in the coming weeks, but it won’t include data that shows how schools and law enforcement agencies responded to tips the system received, said Pacheco, spokesman for the attorney general’s office.

“They are not required to report this information to Safe2Tell, and the limited information we have from those agencies that do report is general, incomplete and not useful to gain a broader understanding of outcomes,” he said in an email.

* * *

When students make Safe2Tell reports via phone, web or app, they go to one of seven analysts with the Safe2Tell Watch Center, which is housed in the Colorado Information Analysis Center, a hub in the Denver metro area that collects and shares information with federal, local and other officials on potential crimes and terrorism acts.

The Safe2Tell analysts then share the information with schools and law enforcement.

Police are called to respond to suicide or mental health reports when there is an “imminent risk” that a person is going to harm themselves or others, school and law enforcement officials said. However, the definition of “imminent risk” is subjective and can vary by school, agency and person.

And it doesn’t explain why in Elizabeth’s case, police were sent to her home after a Safe2Tell report about possible self-harm.

Behaviors such as cutting do not always signal someone is going to attempt suicide. Instead, they are used by individuals to cope, such as when they are feeling overwhelmed or out of control, mental health experts said.

“Not everybody understands non-suicidal self-injury and suicide behaviors,” said Simmons, the counselor in Denver. “They associate cutting with a suicide attempt because that’s what their training lends them.”

Elizabeth said she was not cutting nor injuring herself at the time police checked on her.

The transition from elementary to middle school was difficult for her. She was still adjusting to the emotional and social changes she faced as she went from having few friends to becoming the popular, new girl in school. It was her first boyfriend, and after the breakup, Elizabeth not only shared the photo of someone who’d cut themselves, but also posted a picture on Instagram of herself eating ice cream and watching Netflix.

“That part was definitely just like a dramatic attention response, which I feel like is understandable from a preteen, like, someone figuring out how middle school works,” Elizabeth, now 17, said. “It was only the first semester of me ever being in middle school and me ever having new friends so it was just very different.”

After police arrived, Elizabeth’s parents said they didn’t know whether they should punish her. Both parents said it would have helped had officers provided information on how to access mental health care.

They said neither the school nor a mental health professional followed up with the family after the officers’ visit.

“They were not there to do that,” Jennifer said. “They were there to enforce the law. They’re not there to enforce love and support.”

***

Safe2Tell and local authorities can’t wait to act on a tip when they hear of a potential crisis, Weiser repeatedly stressed.

He said if a report is made outside of school hours, Safe2Tell has to alert those who can immediately respond: police.

Most of the reports Safe2Tell receives arrive outside school hours, with 56% of the 22,332 tips made during the 2018-19 school year coming in between 4 p.m. and 6 a.m., according to the program’s annual report.

Law enforcement officials said that even outside of Safe2Tell, they’re increasingly called on to respond to mental health crises because they are often the only ones available 24/7.

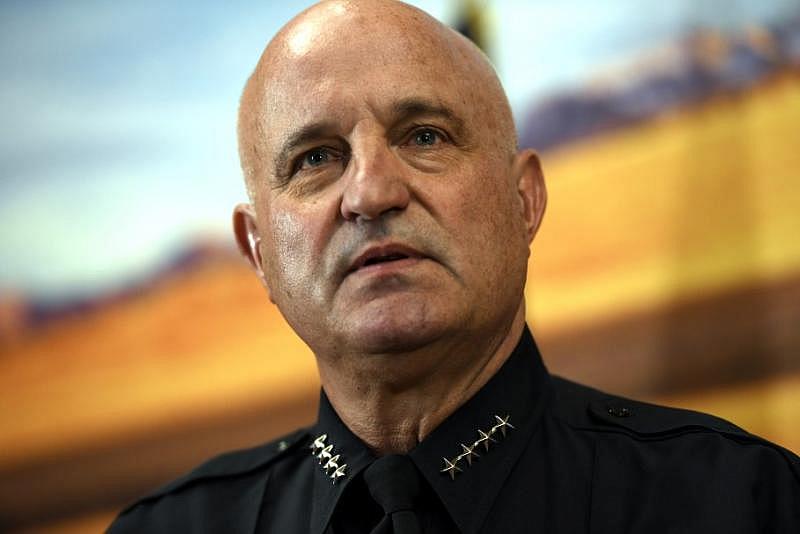

“We’ve sort of become the last resort,” said Boulder County Sheriff Joe Pelle. “We’re not the best. It’s not what any of us went to colleges for, got a degree in.”

Boulder County Sheriff Joe Pelle is pictured at the Capitol in Denver on April 12, 2019. Joe Amon, Denver Post file

Melissa Craven, director of emergency management at Denver Public Schools, said that when school is in session, a psychologist or social worker will check on a student who’s the subject of a Safe2Tell tip. But if it’s outside school hours and an “imminent threat” to someone’s life or others, the district will send officers to a student’s home

Since the start of the pandemic, the school district has “moved our overnight protocols into our daytime protocols,” Craven said, adding that school staff that normally would check on a student after a Safe2Tell report have had to do so remotely.

“If it’s a life safety tip we still have to have eyes on that student,” she said.

With many children and teens still not back in their classrooms, school psychologists, counselors and social workers have had to meet with students through phone and video calls. This has made it harder for staff to respond when students are believed to be at risk of harming themselves, said Jon Burke, mental health and crisis coordinator for Mesa County Valley School District 51

The school district returned to in-person learning in August.

“Safe2Tell really saved our ass through this whole thing,” he said. “It comes down to the fact that we were remote but our kids were still struggling.”

* * *

Susan Payne had an idea.

In 1995, a 14-year-old died in a shooting spree outside of Sierra High School in Colorado Springs. The death echoed the violence that had grown among children and teens in Colorado in previous years

Payne, then a police detective, knew that students know or see warning signs before a shooting or other types of violence, but fear speaking up. She wanted to give them an anonymous and safe way to report what they see and hear.

Payne’s idea: a “crime stoppers” program, such as those used by communities across the U.S., but for children.

The goal was to offer early intervention to troubling behaviors in students in hopes of preventing violence, and talk with students to understand the issues they were facing, said Payne, who led Safe2Tell until 2018 and is now a national school safety and violence prevention expert..

The pilot version of the program launched in Colorado Springs in the late 1990s. Then, two weeks after Payne traveled to Denver to discuss the program with state officials, two teens walked into Columbine High School and opened fire on their classmates, killing 12 students and a teacher before taking their own lives.

Susan Payne, founder of Safe2Tell, is pictured at her home on Sept. 3, 2020. Andy Cross, The Denver Post

At the time, it was the deadliest shooting at a U.S. high school, and in the aftermath, state officials ordered a study focused on how to prevent another such attack, paving the way for Payne’s program to be transformed into a statewide initiative — what’s now known as Safe2Tell.

The events of the early 1990s, including Denver’s Summer of Violence, left school and law enforcement officials with the need to take reports from students seriously and act on them quickly. But it’s what gave rise to zero-tolerance policies, which set harsh punishments for disruptive behaviors, said Shelby Demby, managing director of Restorative Justice Education.

“(This) led to not only the creation of the school-to-prison pipeline but sort of this over-criminalization of normalized youth behavior or mental health issues or substance abuse,” she said.

School shootings and mass shootings are still rare, but since Columbine, Coloradans have faced similar tragedies more often than most. Following the shooting at STEM School Highlands Ranch in 2019, Colorado had the fifth-highest rate of mass shootings, by population, in the nation, and the 10th-highest rate of school shootings, according to a 2019 analysis by The Post.

One of the effects of the Columbine shooting is that it altered how local and state officials thought about youth violence.

As one report on the history of Safe2Tell by The Colorado Trust put it, “(Officials) had always been cautious about potentially dangerous outsiders. Now, suicidal students might become vengeance killers.”

* * *

It’s not unusual for mental health to come into focus after a mass shooting. But the intersection of suicidal behaviors and mass shootings is complicated.

A person’s decision to carry out a violent act, such as a mass shooting, can imply suicidal intentions. But a 2019 study on school violence by the U.S. Secret Service found that suicidality was “rarely the sole or primary factor in an attacker’s motivation for violence. Suicidal ideations were more typically found in combination with, and secondary to, other motives.”

Mental health experts said rhetoric that a person with a mental illness or suicidal thoughts is violent increases stigma and can prevent people from seeking treatment that they need.

“Colorado has a very sad history of violence and mass violence in recent years, so I understand the fears and the need to act urgently when there’s a report of someone suicidal,” said Stacey Freedenthal, an associate professor at the University of Denver’s Graduate School of Social Work.

But, she said, “We need to be mindful of the young person’s needs and not just of our own fears.”

Most people with suicidal thoughts or with a mental illness do not harm themselves or others. Instead, they are more likely themselves to be targets of violence, mental health experts said.

Payne acknowledged this, but said, “When we look at violence prevention, you bottom line have to look at fluidity between suicide and homicide ideation.”

That’s why since its creation, suicide threats were among the reasons someone could call Safe2Tell, she said.

In the decades since, Safe2Tell has become a vital tool in the quest to ensure schools are safe, with similar programs popping up in states from Nebraska to Pennsylvania. The program also has experienced significant growth in Colorado.

In its first year, Safe2Tell received 138 phone calls. By the 2018-19 school year, the overall volume of reports flowing into the system via phone calls, its website and mobile app surged to more than 22,300, according to the program’s annual report.

As Safe2Tell grew over the years, students also began seeking help for another crisis. By the 2013-14 school year, suicide threats had surpassed bullying to become the most common reason students contacted the program.

//

At the same time, in 2014, suicide became the leading cause of death among those between the ages of 10 and 17 in Colorado. Before then, unintentional injuries, mostly from car crashes, caused the majority of deaths for that age group.

Overall, Colorado has one of the highest suicide rates in the nation. More than 1,280 people died by suicide in the state last year. Of those, 60 were children and teens, which is up from 41 deaths among those between 10 and 17 in 2014, according to the latest data from the state health department.

While the number of suicide deaths among adolescents is relatively small, health officials are concerned about how quickly they have increased in recent years.

If the state can reverse the trend, it would not only decrease suicides among children and teenagers but potentially such deaths among adults, too, said Andrea Wood, the zero suicide coordinator for UCHealth in Colorado Springs.

Potential suicide threats remain the leading reason students contact Safe2Tell. More than 3,660 such tips came into the program last year. Another 1,207 tips were for self-harm. And almost 1,000 reports came in for depression.

Potential school attacks made up just 499 reports.

“Did I ever believe (suicide) would be the No. 1 reported concern?” Payne said. “No.”

* * *

Students don’t always realize police are on the other end of Safe2Tell when they report friends they believe might harm themselves. Often, current and former students said, they are just trying to notify an adult, such as a school counselor, that they are worried about someone.

This was the case when Taylor Ogborn, a graduate of Arapahoe High School, sought help for her friend. She made a report with Safe2Tell because she felt it was a better option than calling 911 for a welfare check.

Ogborn thought maybe a paramedic or someone with medical training would respond.

“It’s easier sometimes to deal with a paramedic and treat it like it is, a health problem, than have a police officer show up,” she said. “Police officers aren’t known for mental health training.”

But as she later discovered, when help arrived for her friend, police officers were the ones sent to check on him. The officers handcuffed her friend to transport him to a hospital for a mental health evaluation.

Ogborn, who was in college at the time she made the report, remembers knowing about Safe2Tell by the time she was in middle school. She said she was told when students make a tip about a friend or classmate, “authorities” would check on them.

“Maybe I was just too young to understand that authorities meant police,” she said.

Law enforcement officials said it’s protocol for officers to search and handcuff someone riding in a police car to a mental health facility. One alternative is an ambulance, but they are costly.

“I know it’s pretty traumatic on the kid, but we also have to protect the cop,” said Pelle, the Boulder County sheriff.

But mental health experts said handcuffs send a message to children and teens struggling with mental health issues that there is something wrong with what they are feeling.

Handcuffs, the experts said, also feed into the misconception that people with suicidal ideation or mental health illnesses are dangerous.

“There’s a misunderstanding about things, like suicide and things, like shooting in schools,” said Davidon, the consultant focused on children’s mental health.

“Even though we’re getting much better at, sort of, trying to describe the differences between mental health and these things that people are fearful of, like violence in schools and homicides and mass shootings… the public still makes a connection,” she said.

* * *

Colorado lawmakers have noticed the changes in how students use Safe2Tell, and this summer passed a bill that will no longer require the program to pass information to police or schools if the report is transferred to the state’s crisis line.

The bill also requires the attorney general’s office and other stakeholders to create protocols for referring mental health tips, including those made about another person, to mental health services by Feb. 1, 2021.

“I view this bill as basically capturing, codifying the directions we are working in,” Weiser said.

On Sept. 17, Safe2Tell officials offered their first look at how the program could alter under the bill, although it’s possible the plan could change as discussions are ongoing.

Ellis, the Safe2Tell director, proposed during a Zoom webinar that the program’s analysts offer every person who calls in a report the option to be transferred directly to the Colorado Crisis Services.

Students who make a report through Safe2Tell’s mobile app or website will receive an automated response with information on how to contact the crisis line if the individual or someone they know needs mental health or substance abuse services, Ellis said.

This is because Safe2Tell’s platform does not allow analysts to transfer students to another agency if they make a report using the mobile app or webpage, she said.

Only 5,215 — or 23% — of the more than 22,300 Safe2Tell tips received last year were made by phone. Most reports are made through Safe2Tell’s mobile app and website, according to the annual report.

Since March 2019, the program has transferred calls from students seeking mental health help for themselves to Colorado Crisis Services, provided that the caller agreed.

Self-reporting calls are barely a fraction of the thousands of suicide and mental health tips Safe2Tell receives each year. The majority of those involve students making a report about a friend or classmate.

During the 2018-19 school year, just 75 of Safe2Tell’s reports were from students seeking help for themselves. And of those, 30 were sent to specialists with Colorado Crisis Services. Another three were passed to a national suicide hotlines, according to the program’s annual report.

//

When tips weren’t transferred to mental health specialists, they were sent to schools and police, according to the report.

As they are called to respond to more mental health crises, a growing number of local law enforcement agencies have created co-responder programs that pair officers with mental health workers who can de-escalate potential crises and determine the type of treatment a person might need.

“The ideal situation is that law enforcement agencies are able to have multidisciplinary capabilities, including co-responder models,” Weiser said, adding, “Not every community can manage that model.”

* * *

In 2017, just months after the first time police checked on Elizabeth, they were back.

Elizabeth’s father, Mark was making tacos at his home in Jefferson County when he spotted a police cruiser parking in front of his house and a second car parking in the street behind it.

When the officers got out of their cars, two came and knocked on his front door. The second pair went to a back door.

“I would think, in that sense, what’s going on in my mind is there’s a serious danger that’s in my house, around my house,” said Mark, who also spoke on the condition that only his first name is used. “What should we do? And you have no idea.”

Officers were there to check on Elizabeth after a new Safe2Tell report said she was harming herself.

“I was so angry,” Elizabeth said. “Like, I felt completely, like, first violated that they didn’t trust me when I said I hadn’t. That my dad had to be there and then, I felt once again completely shameful that this had happened.”

The officers asked to check Elizabeth’s body for cuts, so, as she did months earlier, the teen rolled up her sleeves. But this time officers also wanted to see other parts of her body.

She showed them her ankles. Her legs. Her hips. Her stomach.

There were no cuts.

[This story was originally published by The Denver Post.]