Tribune investigation: Erratic code enforcement leaves SLO County renters vulnerable to abuse

This story is part of a larger project, "Standard of Living," by Lindsey Holden, a participant in the 2019 Data Fellowship. The project focuses on the experiences of low-income renters living in poorly maintained housing in San Luis Obispo County.

Other stories in this series include:

Q&A on renter’s rights: What you need to know as a tenant in SLO County

Tribune investigation: What it’s like for SLO County renters stuck in bad housing

We surveyed nearly 200 SLO County renters on their housing conditions. Here’s what they said

Paso Robles couple says landlord covered up unhealthy mold problem. So they sued

Tribune investigation: Inspections protect renters from slumlords. Why did SLO’s program die?

The sign that used to mark the entrance to Grand View Apartments, where hundreds of renters lived with poor conditions for years.

David Middlecamp DMIDDLECAMP@THETRIBUNENEWS.COM

Editor’s note: This is the second story in The Tribune’s “Substandard of Living” series examining the experiences of low-income renters living in poorly maintained housing in San Luis Obispo County. The Tribune spent nine months investigating the issue by talking to residents, conducting surveys, speaking to experts and evaluating government resources.

Long before a group of Paso Robles tenants sued their landlords over unhealthy living conditions at Grand View Apartments, city officials failed to enforce state housing laws and compel the owner to make needed repairs at the complex.

Hundreds of renters living at Grand View — most of whom primarily speak Spanish and work in the area’s agriculture and hospitality industries — had been dealing with bedbugs, broken windows, sewage leaks, cockroaches, ceiling holes and more for years.

Finally, only with help from the San Luis Obispo Legal Assistance Foundation (SLOLAF), were tenants able to file a lawsuit against the property owners in May 2019, citing the property’s unsafe living conditions.

But public records show the city had been aware of problems at the complex since at least 2017 and never used fines or other corrective measures to compel the landlords to fix persistent issues.

The plight of the Grand View tenants offers a window into the shortcomings of local code enforcement efforts and prompted The Tribune to investigate poor rental housing conditions in San Luis Obispo County.

What The Tribune found in examining five years of code enforcement complaints was a system filled with inconsistencies, lax followup and shortages of staff that together often push the burden of ensuring safe housing onto tenants who are ill-equipped to take on landlords.

Even in cities with more robust code enforcement departments, many tenants still fear retaliation from their landlords and avoid calling officials for help until their housing conditions have deteriorated or they’re preparing to move out.

“Grand View Apartments is an example of what can happen when a city does not do code enforcement,” Stephanie Barclay, SLOLAF legal director, told The Tribune in an email. “An investor from out of the county can come in, buy a distressed property, collect rents and let the housing become so dilapidated that it becomes slum-like.”

“It’s detrimental for the entire community, not just the tenants living in those conditions,” Barclay continued. “Tenants are afraid to speak up because it is so difficult to find affordable housing in San Luis Obispo County — they feel like they have to put up with whatever they’ve got.”

A Grand View tenant’s wall shows splotches of rusty red blood where bed bugs were smashed. Lindsey Holden LHOLDEN@THETRIBUNENEWS.COM

CODE ENFORCEMENT ACROSS SLO COUNTY

San Luis Obispo County and its seven cities all deal with substandard rental housing in different ways, and their code enforcement staffing and budgets are good barometers for whether local governments prioritize this work.

San Luis Obispo has the most staff and the biggest budget of any city in the county, with four code enforcement personnel who earn more than $200,000 collectively.

The county — which oversees unincorporated communities, such as Los Osos and Nipomo — employs seven code enforcement staff members and has a budget of about $1.2 million.

But in most communities, there’s only one full-time or part-time employee overseeing thousands of tenant households.

For example, Morro Bay, Paso Robles and Pismo Beach reported they each have only one part-time code enforcement officer and budgets of less than $30,000 each.

That kind of limited staffing makes it challenging for cities to properly oversee rental properties or conduct outreach to vulnerable communities to help them understand they can turn to code enforcement for help.

“To the extent that code enforcement is complaint-driven, it’s almost totally ineffective for that most vulnerable population that is really most likely to be living in substandard housing,” said Lucas Zucker, policy and communications director for the Central Coast Alliance United for a Sustainable Economy (CAUSE), a nonprofit that works with tenants in Santa Barbara and Ventura counties.

“Those are the people who are just as afraid of reporting it to the government as they are afraid of reporting it to their landlord.”

Illegal garage conversions are frequently used to create extra housing units in San Luis Obispo. They’re legal with a permit, but makeshift bedrooms are frequently created without the city’s knowledge. City of San Luis Obispo

INCONSISTENT TRACKING AND ENFORCEMENT

These shortcomings became clear when The Tribune examined substandard housing complaints filed by residents in the cities and communities around the county.

To get a feel for the problems, The Tribune submitted Public Records Act requests to the county and its seven cities asking for these complaints over the last five years.

The results were all over the map.

A few cities returned hundreds of complaints, while others said they hadn’t received a single report of substandard rental housing.

Some cities’ records said “substandard rental” without going into more detail. Other cities provided more details about the specific nature of the complaints or scanned copies of handwritten reports submitted by residents.

San Luis Obispo reported the most substandard rental housing complaints with 129, after filtering out complaints over garage conversions, which are now legal in the city with a permit.

Complaints described a variety of issues, including rodents, hazardous electrical wiring, plumbing problems and leaking roofs. Mold was the most commonly reported problem in San Luis Obispo.

Blanca, an Oceano tenant, lives with old, dirty carpet in her living room. She bought a rug to cover the carpet, which is peeling away from the floor underneath. Laura Dickinson LDICKINSON@THETRIBUNENEWS.COM

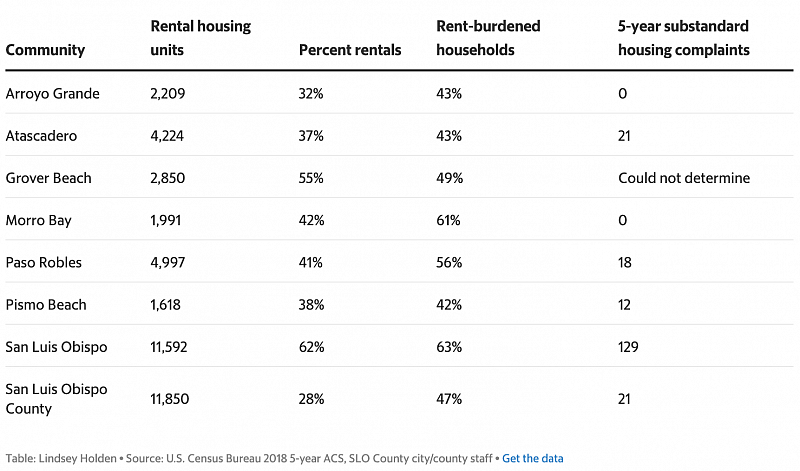

In total, unincorporated San Luis Obispo County (meaning areas outside city limits) has 11,850 renter-occupied housing units — more than the city of San Luis Obispo, which has 11,592 renter-occupied units, according to U.S. Census Bureau data.

Yet there were only 21 complaints from tenants in those areas — meaning the city had almost six times more reports of substandard housing than the county’s jurisdiction.

“The county code enforcement team investigates complaints that we receive in the unincorporated areas of San Luis Obispo County,” said Erika Schuetze, communications manager for county Planning and Building, when asked about the low number of complaints. “We can’t speculate on whether or not there are violations occurring that aren’t being reported to us.”

But the small number of complaints stands in stark contrast to what tenants — many of whom live in unincorporated working-class neighborhoods in Oceano and San Miguel — told The Tribune about their rentals in nearly 200 surveys.

They reported dealing with plumbing problems, mold, missing smoke detectors, roof leaks and other hazardous conditions. Some tenants, especially those in the North County, were living with visibly broken windows and other issues but were too scared of landlord retaliation to talk to Tribune reporters who knocked on their doors.

Most survey respondents in those communities said they’d never reported problems to code enforcement, demonstrating one of the most notable gaps in the system.

LITTLE OVERSIGHT OF RENTAL HOUSING

How cities track rental housing issues varies dramatically from one municipality to another.

Rental units make up at least one-third of the housing stock in all seven of the county’s cities, according to Census data. About 28% of all housing units in unincorporated areas of the county are rentals.

At least 40% of all tenant households in the seven cities and the county are rent-burdened, meaning they spend 30% or more of their income on housing.

Grover Beach doesn’t separate rental housing complaints from other issues reported to code enforcement, making it impossible to learn whether tenants struggle with poor conditions, or even whether they report problems to the city.

Bruce Buckingham, community development director, said the city doesn’t have many large apartment complexes and hasn’t seen a high percentage of issues related to substandard housing.

The city has 373 rental housing units in complexes that have at least 10 apartments, according to Census data.

If city staff became aware of issues, they could have internal discussions about changing the code enforcement tracking system, Buckingham said.

Meanwhile, Arroyo Grande and Morro Bay reported no substandard rental housing complaints at all. Both have seen their code enforcement resources dwindle amid impacts from COVID-19, but even before the pandemic, no issues were being raised.

Arroyo Grande — which has 2,209 renter-occupied units — previously employed up to three part-time “neighborhood service technicians” at the Police Department who dealt with code and parking enforcement, City Manager Whitney McDonald said.

But the city furloughed its non-sworn police personnel due to coronavirus budget cuts, and then the one remaining code enforcement staff member moved away.

SLO COUNTY RENTAL HOUSING AND CODE ENFORCEMENT

San Luis Obispo County renters living in poor housing are often too afraid to report their situation to their local government. But they also face an inconsistent code enforcement system that's understaffed and doesn't always track complaints.

“From my perspective, it does not appear that Arroyo Grande has a problem with substandard rentals in the sense that it is not a prolific or even regular issue that we encounter,” McDonald said in an email. “In addition, our housing stock is generally in good shape and, for various reasons, properties in our community are well maintained overall.”

“From a statistical standpoint, however, it is likely that there are at least some substandard units in our city,” she continued. “We just do not receive complaints about them.”

For the time being, the city’s building official is overseeing code enforcement, McDonald said. And the city is beefing up its fine and citation system in the wake of COVID-19 restrictions, she said.

In Morro Bay, which has 1,991 renter-occupied housing units, community development director Scot Graham said the city doesn’t record all complaints until they become code enforcement cases. Cases that come in through the city’s online portal are tracked, but complaints received by phone don’t always end up in the system.

“It’s not something we get complaints on very often,” he said of substandard housing.

The city previously had two part-time code enforcement officers, but COVID-19 financial impacts caused one position to be frozen after the staff member left the department, Graham said. The city beefed up its code enforcement program after a 2015 Grand Jury report found it lacking and suggested staff establish a “proactive managed code enforcement process.”

Even so, the city’s code enforcement process remains primarily complaint-driven.

“The Grand Jury report suggested moving to proactive code enforcement, implementing a way to track complaints electronically and hiring code enforcement officers,” Graham said. “We did all those things.”

WHAT WENT WRONG AT GRAND VIEW?

The situation at Grand View occurred in part because the city of Paso Robles takes a notably hands-off approach to enforcing state rental housing codes. This can leave tenants at greater risk of suffering in poor living conditions or facing a struggle to enforce their rights in civil court.

More than 45% of Paso Robles renters identify as Hispanic or Latino — the highest percentage of any city in the county.

Substandard housing complaints and email correspondence obtained by The Tribune show city building officials tend to dismiss reports of substandard housing as “civil matters” or “tenant-landlord issues” in which they decline to become involved.

Grand View tenants experienced this situation firsthand.

Renters discarded mattresses and furniture behind the Grand View Apartments complex in Paso Robles because they were infested with bedbugs and cockroaches. David Middlecamp DMIDDLECAMP@THETRIBUNENEWS.COM

The city first began hearing about problems at the complex in May 2017, when renters reported poor conditions to code enforcement, including “excess blight on property, bed bugs, multiple broken windows — on second floor children hang out broken windows,” according to the complaint.

A California Rural Legal Assistance Foundation (CRLA) attorney representing a Grand View tenant also sent the city and the property manager a letter describing bedbugs and broken windows, in addition to mold, exposed wiring and a parking lot prone to flooding.

In response, the city and the county Public Health Department inspected the complex on May 24, 2017.

Inspection notes taken by city staff and a letter from a county environmental health specialist described findings that included broken windows, mold, missing smoke and carbon monoxide detectors, and cockroach and bedbug infestations — violations of fire and state housing codes.

Brian Cowen, city building official, told The Tribune that staff that “corrections were observed with a follow-up inspection.” But documents provided by the city don’t indicate when that inspection occurred or what the city ordered the owners to fix.

The next documented inspection occurred more than a year later, following a fire at the complex in September 2018.

In November 2018, Cowen said in an email that “the city has become increasingly concerned with the condition of the property.”

“While the site provides valuable housing for residents, we are hearing that conditions may have degraded to bordering substandard,” Cowen wrote.

A Grand View tenant’s bedroom walls were covered in black mold. Lindsey Holden LHOLDEN@THETRIBUNENEWS.COM

GRAND VIEW TENANTS FORCED TO LIVE IN SQUALOR, DISPLACED

In spite of knowing about poor conditions at the complex, emails show Cowen opted not to investigate visible problems at Grand View brought to his attention by other city staff members.

In January 2019 — just months before tenants would file their lawsuit — John McCabe, a city building inspector, sent Cowen an email describing serious flooding in the Grand View parking lot.

“Not sure who can help with this but over at Grandview Apartments there’s some major flooding in the parking lot,” McCabe wrote. “Four to 5 inches of standing water and you’re losing parking spaces. I believe there’s two storm drains in the puddles but they’re blocked up perhaps? I was hoping you guys could get this to the right people. I’ve included some pictures.”

Photos show cars driving through deep stagnant water — a substandard condition under California health and safety codes.

Even so, Cowen wrote back: “It’s a private issue for the property owner/management to deal with.”

McCabe responded: “OK, 10-4.”

A Paso Robles city staffer sent a photo of deep stagnant water in the parking lot of Grand View Apartments to Building Director Brian Cowen, asking if anything could be done. City emails show Cowen declined to look into the flooding. City of Paso Robles

The flooding is not mentioned again in correspondence or documents The Tribune obtained through its PRA request.

“The issue was a plugged or failed storm drain on-site,” Cowen wrote in an email to The Tribune. “Water would pond in the parking lot following a rain. I don’t recall the water staying around long enough to present a health & safety issue.”

In May 2019, a full two years after issues first came to light, tenants and SLOLAF sued their landlords, Ebrahim and Fahimeh Madadi of Santa Barbara County, over the persistently poor living situations they had endured.

Tenants’ court declarations described horrific conditions.

One renter, who had lived at Grand View since 2010 with her husband and three children, said she had to throw out food because cockroaches got into it. She said her son and her husband received bedbug bites that caused rashes and became infected.

Another tenant described raw sewage backing up into her toilet and bathtub. When she showered at home, she stood on a step stool to avoid touching the sewage. She eventually began showering at her children’s house after the complex’s handyman didn’t fix the problem.

David Hamilton, an attorney representing the Madadis, declined to comment, citing ongoing litigation. However, a brief filed in the lawsuit claims the couple “are both in their late 70s and suffer from numerous health issues. The Grand View Apartments represent their only real estate investment and until the filing of this litigation they had no actual knowledge of the conditions of the (complex).”

After the lawsuit was filed, the city finally cited the Grand View owners for the first time. City staff and Public Health Department personnel once again inspected the complex.

A letter to the property owners shows inspectors once again found many of the same issues that existed in 2017, including dozens of expired fire extinguishers, at least nine apartments with missing smoke alarms and three units with missing carbon monoxide detectors.

A few months later, the landlords opted to close the complex and sell it rather than pay for millions of dollars in repairs.

The tenants were all evicted and forced to find new places to live — a challenge in Paso Robles, which has a 1.9% rental housing vacancy rate, according to Census data.

At the time, Allen Hutkin of Hutkin Law Firm, who’s representing the Grand View tenants with SLOLAF, appealed to the City Council for help finding housing for the tenants.

“Your city is now facing a humanitarian crisis on its hands,” Hutkin said. “This crisis is going to fall on your working poor.”

The evicted tenants struggled to find new housing, especially due to the stigma of having lived with bedbugs. In spite of the conditions at Grand View, some renters fought to stay because finding a new home was so challenging.

“We live in the United States,” one tenant told The Tribune in Spanish. “And this is how we live.”

Grand View was eventually sold to new owners, who are in the midst of renovating the complex and are beginning to rent out the first revamped units.

The tenants’ lawsuit continues to move through the court system and will likely go to trial in 2021, Barclay said.

CODE ENFORCEMENT AND LEGAL AID

Even though hundreds of Paso Robles residents were displaced from their homes and forced to live in terrible conditions for years, Cowen told The Tribune that he sees what happened at Grand View as a “huge success” because the property was sold to a new owner.

The city was aware the Grand View owners were unwilling to fix the substantial problems at the the property, Cowen said. Instead, they were making only small repairs to keep the city off their backs, he said.

When asked why the city never fined the previous owners or took any punitive action against them, Cowen said that fines “muddle the situation.” Taking further steps, such as placing a lien on the property, would have made it more challenging to sell, he said.

“What really needed to happen, like with Grand View, is because that previous owner wasn’t willing to deal with the issues, they needed somebody else to step in with the right idea, with the right mentality that wanted to be a good neighbor, a good landlord, good owner and take care of it,” Cowen said.

“And if they had been (holding), let’s say, $100,000 in fines, a lien on there, it actually would’ve made it more difficult from the standpoint of a buyer. It would’ve been one more thing to deal with, and it would’ve made it more difficult to actually resolve the issue.”

Cowen insisted the tenants had more power than Paso Robles did — that the city preferred to be more like a “team member,” rather than taking charge of the situation.

Francisco Ramirez shows a welt on his arm from a bedbug bite. Ramirez a three-year resident of Grand View Apartments, said black mold, bedbug bites, roaches and mice were common at the Paso Robles complex. David Middlecamp DMIDDLECAMP@THETRIBUNENEWS.COM

“The real core of the problem in these situations is like in Grand View, you have an owner that is very much aware of the issues, and they’re just not willing to fix them,” he said. “The tenants then had a lot more leverage than the city ever could’ve had with little administrative fines. The tenants were able, by going through the legal process, to cut off the income, and that’s the language that the owner understood.”

But SLOLAF and California Rural Legal Assistance Foundation (CRLA) attorneys see the situation differently.

“(Tenants) are often too busy working two jobs to spend time learning their rights and looking for other housing,” said Barclay, SLOLAF legal director, in an email. “Putting the burden on the tenants to pursue civil remedies for uninhabitable housing just isn’t realistic or adequate in most situations.”

Frank Kopcinski, CRLA San Luis Obispo directing attorney, told The Tribune it’s better for cities to enforce state health and safety codes, rather than leave renters to fend for themselves. Tenants frequently find the court process “daunting” and may not understand their rights and what they’re entitled to as renters, he said.

“CRLA does not have the capacity to enforce the housing rights of all the renters who need assistance in San Luis Obispo,” Kopcinski said in an email. “We are a small legal aid office with only a few attorneys. If cities strictly enforce the housing codes, there would be much less unmet need in the county.”

Some Grand View Apartments renters kept their belongings in suitcases and plastic containers to prevent bedbugs and cockroaches from getting in. David Middlecamp DMIDDLECAMP@THETRIBUNENEWS.COM

ENSURING SAFE HOUSING IN PASO ROBLES

Paso Robles did devote resources to helping tenants find new housing after Grand View closed. But the city has not substantially changed the way it conducts code enforcement to prevent other renters from having to endure similar conditions.

Mayor Steve Martin told The Tribune he didn’t have a definitive answer for why the city never fined the Grand View owners, in spite of the complex’s repeated housing code violations.

The City Council has had to cut Paso Robles’ budget due to the financial impact of COVID-19, which means the city likely won’t be able to expand its staff or add services in the near future, Martin said.

“We feel that the city should have the ability and the direction to aggressively pursue substandard housing,” Martin said. “Obviously that’s something that takes more staff and time and expense, which we’re all feeling the pinch of right now.”

“But that’s not really the excuse,” he continued. “Moving forward, we need to make sure that housing is safe and habitable for everyone in the city.”

John Mezzapesa, a San Luis Obispo code enforcement officer, inspects a bathroom sink in a rental home in the city. San Luis Obispo has more code enforcement staff than any city in San Luis Obispo County.

HOW SLO DOES CODE ENFORCEMENT

San Luis Obispo’s substandard rental housing code enforcement is more aggressive than other cities in the county, but renters fearing illegal retaliation from their landlords may still avoid reporting problems in their units. Poor housing then gets passed from one tenant to the next without anything changing, likely deteriorating further over time.

The city in 2017 increased fines for landlords who don’t make needed repairs and planned education efforts to help renters better understand their rights and available resources.

San Luis Obispo staff ultimately end up fining about 50% of property owners required to make repairs, said Cassia Cocina, code enforcement supervisor.

“Code enforcement works with the property owner to come into compliance,” Cocina wrote in an email. “However, if corrections are not made in a timely manner, they are issued administrative citations that progressively increase if there is continued non-compliance.”

The first citation comes with a $100 fine, and property owners get 30 days to pay, although a second $500 citation could come 10 days after the first one if the city doesn’t get a response within that time period, Cocina said. A third-tier citation costs $1,000.

Most citations are issued after inspectors find non-permitted construction, she said. If significant repairs are made without help from licensed contractors and city inspectors, they could contribute to poor conditions down the road, Cocina said.

Owners who don’t pay the city previously had the fine added to their property taxes in the form of a lien. Next year, the city will start sending owners to collections, instead, Cocina said.

John Mezzapesa, a code enforcement officer for the city of San Luis Obispo. The city has more code enforcement staff than any other city in San Luis Obispo County. Laura Dickinson LDICKINSON@THETRIBUNENEWS.COM

Although not all owners pay the fines, they are useful in convincing some to contact the city and begin the process of fixing up their rentals, Cocina said.

John Mezzapesa, code enforcement officer, said the department also conducts outreach with the Cal Poly community to help educate student renters about their rights.

Even so, the city still sees “a lot of hesitancy for a lot of tenants to call code enforcement,” Mezzapesa said.

“From our point of view, what we see a lot of with tenants complaining is they’re fed up with it,” he said. “They’ve gone through the process with the landlord and they’re not getting the response that they need, and they actually do feel it’s a health and safety violation. Or they’re at the end of their lease and they don’t feel like the retaliation can happen because they’re going to be leaving anyway.”

Many times, tenants don’t know the point at which they should contact code enforcement or fear a crackdown from their landlords, who have control over their housing.

It’s illegal for landlords to evict tenants for reporting poor conditions to code enforcement. But renters — many of whom likely don’t know their rights — don’t want to fight their landlords in court or don’t realize they have a right to do so.

“That boils down to a civil issue that they need to follow up on, and a lot of times, they just don’t want to deal with that headache,” Mezzapesa said. “And so then (they) go back to square one where they don’t report anything. And then those conditions continue to the next tenant and the next tenant until someone else gets fed up with things.”

This story was produced with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, the Center’s engagement editor, Danielle Fox, and KTAS-Telemundo.

[This story was originally published by The Tribune.]