Americans’ desperate need for relief on drug prices is lost in a season of political theater

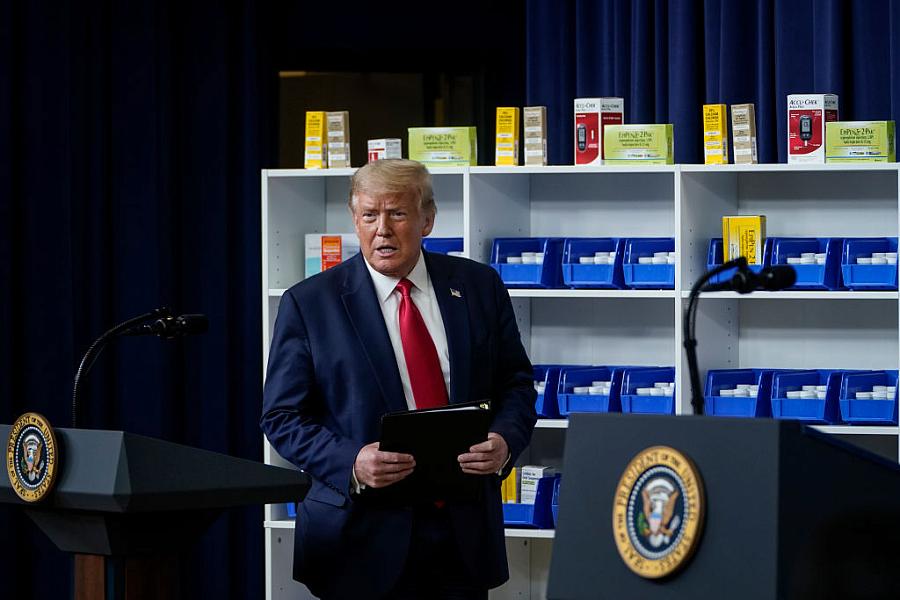

(Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

The high price of prescription drugs makes good election year politics. Until the death of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg muddied the future of the Affordable Care Act, drug prices were the major health policy issue going forward —outside of COVID-19. Government inaction over the high price of prescription medicines resonates with voters who are unable to keep up with constantly rising prices for their drugs.

In many parts of the country, rival candidates for Congress are playing up their prescription drug bona fides in ways I have not seen before. High drug prices are making for good politics.

In Maine, for example, Sen. Susan Collins touts a bill she passed that allows local pharmacies to counsel patients about more affordable options for their prescriptions. Her rival Sara Gideon says drug companies spend millions in Washington and keep getting their way, and promises she’ll work for her constituents — “not the drug companies.” In Montana, Republican Sen. Steve Daines, says he was “taking on Big Pharma to lower prescription drug prices” while his rival, Gov. Steve Bullock accuses Daines of giving “billions in tax breaks to them while blocking lower prices for you.”

In Arizona rivals for a Senate seat, too, have embraced drug prices as a talking point, with Republican incumbent Martha McSally “taking on China and the big pharmaceutical companies to make sure prescription drugs are safe, affordable, and made in America,” as her ad puts it. Mark Kelly, the former astronaut running against her, is more specific, saying, “Washington politicians look the other way after taking millions from drug companies. Drug companies protect their profits, and those politicians, they protect their careers.” Kelly says he isn’t taking “a dime” from any corporate PAC, and says he’ll push for Medicare to negotiate lower drug prices with drug makers and make cheaper generic drugs more available.

And in northern Minnesota, Democrat Quinn Nystrom is running for Congress with an ad that tells viewers she went to Canada to bring back insulin for a fraction of what drug companies charge here, “but Pete Stauber (her rival) went to Washington and voted against making health care prescription drugs more affordable.” She’s referring to the stalled House bill that called for Medicare to directly negotiate prices with drug companies.

Drug prices are a big issue in Minnesota, says 47-year-old Travis Paulson of Eveleth, a small town in the state’s far north. Paulson has been a Type 1 diabetic since he was 14, and serves as the managing director of the Northern Minnesota Advocacy Group, which helps Minnesotans get drugs in Canada. Since the pandemic, however, he and thousands of others using Canadian drugs have had to pay far higher prices in the U.S.

Earlier this year the Minnesota legislature passed legislation that requires drug companies to make a 30-day emergency supply of insulin available to those with an urgent need and unable to afford their medication, with a copay of no more than $35. The law was passed after the widely reported death of Minnesota resident Alec Smith, a 26-year old Type 1 diabetic who died in 2017 because he couldn’t afford his insulin. The law was slated to take effect July 1, but the drug industry sued on that day, asking a federal court to declare the law unconstitutional and prevent the state from enforcing it. “They did something I didn’t think was possible,” said Gov. Tim Waltz. “They’re more hated than COVID-19.” The law is still in effect while the challenge continues. “It had to be rewritten several times as the industry picked it apart,” Paulson said.

“It was extremely hard to pass this bill,” Paulson told me. “Minnesota has become a proving ground for what can get passed and what can’t. If they can stop us here, they can use the law to stop other states too.” Paulson himself has been featured in an ad made by the advocacy group Patients for Affordable Drugs, which has launched a seven-figure election season ad blitz this month in 15 states.

David Mitchell, who heads Patients for Affordable Drugs, told me, “We want to do everything in our power to ensure drug prices are part of the election. We are calling on people nationally in ads in 15 key states to vote for candidates who will stand up to Big Pharma and fight for lower drug prices.”

The pain and worry voiced by participants in Mitchell’s ad campaign are real. It’s hard to say the same of the various proposals President Donald Trump has announced over the past weeks to remedy one of the worst side effects of prescription drugs — super high prices. The president’s proposals appear to be little more than symbolic political gestures in the run-up to the election, designed to distract from the unchanged political realities.

Part of the actual political reality in this case includes strong measures to lower the price of drugs, like those outlined in the prescription drug legislation passed by the U.S. House a year ago. That measure called for Medicare to negotiate prices with the drug industry, a method used by many other countries to keep drug prices low. However, the consensus among academics and others who follow drug price legislation is that Americans won’t get relief from high drug prices any time soon.

“My general view is that it is very hard to fix drug pricing in the U.S. Announcements that don’t get implemented do nothing for patients.” — Dr. Peter Bach, Center for Health Policy Outcomes at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center

The three orders Trump announced at the end of July would allow some drugs to be imported from Canada; make changes in the way discounts negotiated by pharmacy benefit managers are passed on to Medicare beneficiaries; and require government-sponsored dispensaries to make insulin and epinephrine available to low-income patients who don’t have health insurance or they have insurance with high copays. Columnist Michael Hiltzik of the Los Angeles Times points out that those dispensaries already make those drugs effectively free to patients with incomes below the poverty line.

At the time the president said he had a fourth order up his sleeve but wanted to first meet with the drug companies. “We may not need to implement the fourth executive order,” he said at the time, calling it “a very tough order.”

In mid September, however, Trump announced that the fourth order was necessary after all. It repealed the older order calling for Medicare to pay the same price for Part B drugs based on what other developed nations pay and replaced it with one that would include Part B and Part D drugs as well — the drugs Medicare beneficiaries buy themselves at the pharmacy. Under this arrangement Medicare could refuse to pay for drugs in the U.S. that cost more than what a group of other countries were paying for the same drugs. This solution is sometimes referred to as international reference pricing or “most favored nations” policy.

Academics who specialize in drug pricing policy are not betting that drug prices will fall any time soon. In fact, they continue to rise. Good Rx, a company that tracks drug prices, found that in July 42 drugs increased their prices by an average of 3.3% in July, an increase over the previous year.

“An executive order does not necessarily do anything. They lack pretty critical details, and the actual rules do not exist.” — Loren Adler, associate director of the USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy

Law professors Rachel Sachs of Washington University School of Law and Nicholas Bagley of the University of Michigan School of Law, writing in New England Journal of Medicine, note other problems with the president’s approach — particularly allowing states to import drugs from Canada. They argue, for example, that the Department of Health and Human Services “has offered very limited guidance to the states on how they might show that importation will reduce costs,” and the order raises questions of feasibility and legality. They conclude that the administration’s other executive actions on drug pricing appear to be “political theater designed to mollify the public and restive states without overly antagonizing the pharmaceutical industry.”

“An executive order does not necessarily do anything,” Loren Adler, associate director of the USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy, told me. “They lack pretty critical details, and the actual rules do not exist.”

Dr. Peter Bach, who directs the Center for Health Policy Outcomes at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York City, is also dubious of the president’s executive orders. “My general view is that it is very hard to fix drug pricing in the U.S.,” he told me. “Announcements that don’t get implemented do nothing for patients.”

On Thursday, though, the president made yet another surprise announcement. He promised to send some 33 million seniors a $200 drug discount card presumably to be used to defray some of the huge out-of-pocket costs seniors (and others) have to pay for their medicines — costs that can amount to as much as 50% of the price of the drug. Such a card would hardly make a scratch for someone taking expensive medications such as Humira and Stelara for Crohn’s disease for example — these drugs can cost upwards of $20,000 for a course of treatment. “Nobody has seen these before,” Trump said. “These cards are incredible. I will always take care of our wonderful senior citizens. Joe Biden won’t be doing this.” The consumer advocacy group Public Citizen described the move as a “pathetic attempt to bribe [seniors] for their votes,” as Politico reported.

A discount card that someone might use at Target to buy garden supplies really going to lower drug prices? That’s pretty far-fetched. It so happens that in reporting this story I spoke to a 31-year old woman Jacquie Persson who lives in Waterloo, Iowa, and has suffered from Crohn’s disease since she was in her early 20s. She is also featured in one of the ads that Patients for Affordable Drugs is running during the presidential campaign. The injection she must take every four weeks costs $21,965, and her health insurance from her employer covers all but $200. “I know my situation could change at any time,” she says. She or her husband could lose their jobs and the insurance they so desperately need. That’s hardly a trivial concern in these days of the pandemic and widespread losses in employer health coverage.

A $200 discount card doesn’t begin to solve this real pocketbook issue for Persson, Paulson, and countless other Americans struggling with expensive illnesses who would still like to see the country’s political leaders offer real solutions to the high price of pharmaceuticals.

Veteran health care journalist Trudy Lieberman is a contributing editor at the Center for Health Journalism Digital and a regular contributor to the Remaking Health Care column.