Bringing data and personal experience together to show how community violence shapes lives, fates

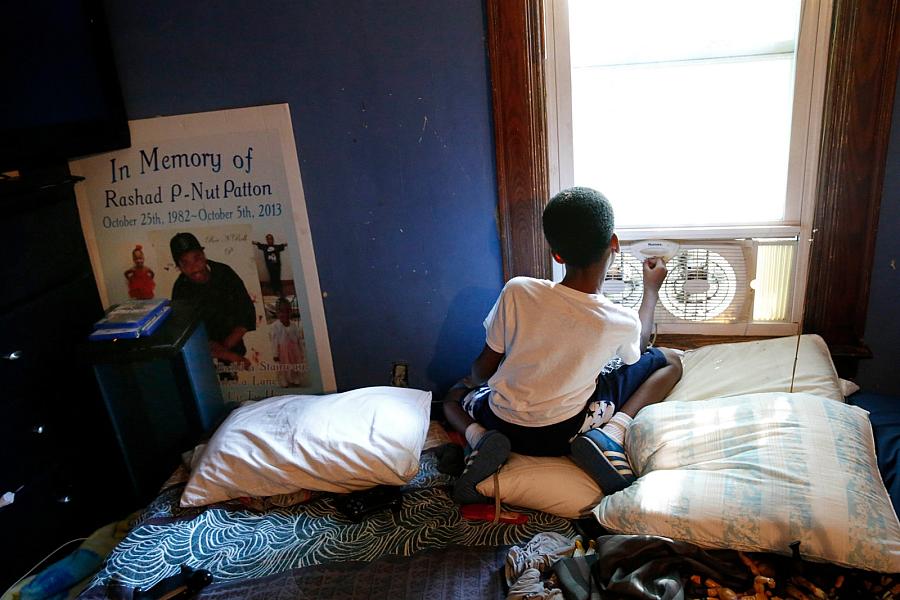

Jayden Lawson, now 9, lost his father to violence in 2013. At Jayden’s left is a poster from his father’s memorial service. It used to be a comfort to him, but on this day, he told his grandmother that he doesn’t want it in his room anymore.'' Sharon Cantillon/The Buffalo News

So many children have a story.

Young men whose older brothers were shot. Others with fathers in prison. Little boys whose parents won’t let them walk to the end of the street out of fear they will encounter gangs and violence.

It became clear to me while covering education in two of the country’s poorest cities that violence is taking an incredible toll on young people – and in many cases setting the trajectory for their future. I have met scores of young people whose lives and fates had been shaped by violence in their communities.

A growing body of research and conversations among educators reaffirmed what I heard when I spoke to young people.

But how can journalists write about an issue so few people outside of inner city communities understand, much less relate to?

That was my goal as I set out to cover how violence impacts children – particularly in the classroom – for my USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism fellowship project: In Buffalo's children, wounds no one sees.

Here is how I tackled it:

Data: I knew that for this project to resonate beyond a relatively small circle of people familiar with the topic I would need to do more than string together stories about children touched by violence.

I thought if we could identify the neighborhoods where children are exposed to the most violence, we could then examine what life is like for young people in those specific communities.

The first step was to obtain police data that would show us where the most violence has been occurring in Buffalo. Often this information is reported by ZIP code, or limited to certain crimes. So we worked with police to get data that showed us the specific location of each reported violent crime, which we then used to identify the census tracts and neighborhoods where the most incidents were reported.

I met with trusted sources, who helped brainstorm a list of things that might demonstrate outcomes of that exposure – everything from juvenile justice crime statistics to academic risk factors. I reviewed national research to see if there were things we should ask for that might show correlations in our own community. Much of the data we wanted was not publicly available, so I relied on sourcing to obtain the information. We didn’t get everything we asked for, and even what we did get didn’t necessarily show what we thought it would.

For example, we looked at whether students from the most violent neighborhoods had more suspensions or attendance issues. The data did not show a clear correlation, largely because those issues were so prevalent all over the city.

What we did find, using enrollment information, was that nearly half of the students in the Buffalo Public Schools lived in the most violent neighborhoods – a figure we thought showed the overwhelming scope of the issue. We also learned that those children attended nearly every school in the district, allowing them to often fly under the radar and go unnoticed. That also meant their own trauma and exposure could have an impact on many other children with whom they attended school.

We coupled our own data analysis with statistics from the district about how many students had witnessed violence, or been shot themselves, to create a framework for the story.

Research: We knew all along any data analysis we conducted would be limited since we had no way of tracking individual students, and certainly not in the long-term to assess direct outcomes.

That’s when we looked to national research, much of which I found through my Annenberg resources, to connect our finding – that many Buffalo children live in neighborhoods plagued by violence – to the broader research showing what that could mean for them. That included altered brain development, changes in behavior and ultimately trouble in the classroom.

Sessions during the Annenberg training seminars gave me a deeper understanding of this research, particularly as it pertains to brain development, enabling me to ask questions of some notable experts in this area. These sessions also gave me a guide for what other research I could use in my project.

A powerful story: The data and research set a strong framework for the project, helping make a case to readers that this is an important issue in the community. And we knew there were countless stories in our community we could tell to put a human face on the topic. The next, and perhaps most important step, was finding the most powerful one.

Sadly, it found us with the shooting of an 11-year-old boy named Juan Rodriguez.

The shooting happened several weeks before I attended the Annenberg training seminar, and I knew the shooting would ultimately be a key part of our project. But I wasn’t sure how. Juan’s experience was a very extreme example, and we wanted to also convey the subtler ways children are impacted when violence happens in their neighborhoods.

It was during a session listening to Nancy Cambria of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch talk about her project looking at trauma in a community near Ferguson, Mo., I was inspired with the idea to focus our reporting not on Juan, but on the other children in the neighborhood where he lived.

My colleague and I spent much of the summer visiting Humason Avenue, meeting families on the street and talking to them about how they had been touched by the incident. These visits led us to Cheryl Ruttlen-Brown, who had a long history as an anti-violence advocate. Her own son had been killed when he was just shy of 30, leaving her with custody of his young son Jayden.

We knew Ruttlen-Brown and her family would be a key part of the story, largely because she was so open about their experiences and articulate about the impact of violence on children and the community. These are two key elements to any successful narrative.

We were still working on the project when a young man involved in Juan’s shooting – Detavion Magee – was set to go on trial. This turned out to be critical, since attorneys delved into great detail about what happened that night, as well as the background information of the people involved. This allowed us to essentially recreate what happened on Humason that night, and what Juan and his siblings experienced. Juan’s sister Alina emerged as a key character.

Juan and Alina would help us depict the immediate toll violence takes on children. Jayden’s story allowed us to take a more prolonged view, illustrating how a child still struggles several years after.

Our other reporting had led us to older men who exemplified the more long-term impact, and we wanted to include that in the story as well. We also wanted to keep the story focused on Humason, and how a single incident could connect different people.

What about Detavion Magee, I thought?

Based on previous reporting, I suspected he, too, had a story to tell. We did not have access to him directly when he was on trial, but one day during the proceedings I approached his mother. She agreed to be interviewed and talked in great detail about her son’s childhood, violence in the family and his encounters with gangs when he was still a high school student.

It was a final piece that allowed us to show a wide-range impact.

Student voices: Finally, we wanted to produce more than a traditional newspaper project. We wanted our project to spark a conversation and offer a platform for the people most affected – students.

We worked with a community arts organization to help students produce their own video about the topic. This was an ongoing partnership that included the News hosting the students for field trips and discussions on the issue. This not only introduced them to the project, but allowed them to experience our professional work environment.

I continued those conversations throughout the project, helping facilitate discussions and connect them with sources for their video. It was important to allow the students to be the driving force, though, so we encouraged and supported them in coming up with their product, but did not dictate what we wanted.

These stories are never easy. But one thing that helped me push through was knowing just how many people in our own community wanted so badly to fix this issue – but either didn’t know how or didn’t have power to. We talked to dozens of people who never appeared in the story, from teachers and social workers, to community advocates and data analysts, to parents and children.

They, too, all had a story to tell, and wanted to help. I can only hope our project will inspire the changes that are so badly needed.