A broken system: Investigating youth psychiatric residential treatment facilities in Arkansas

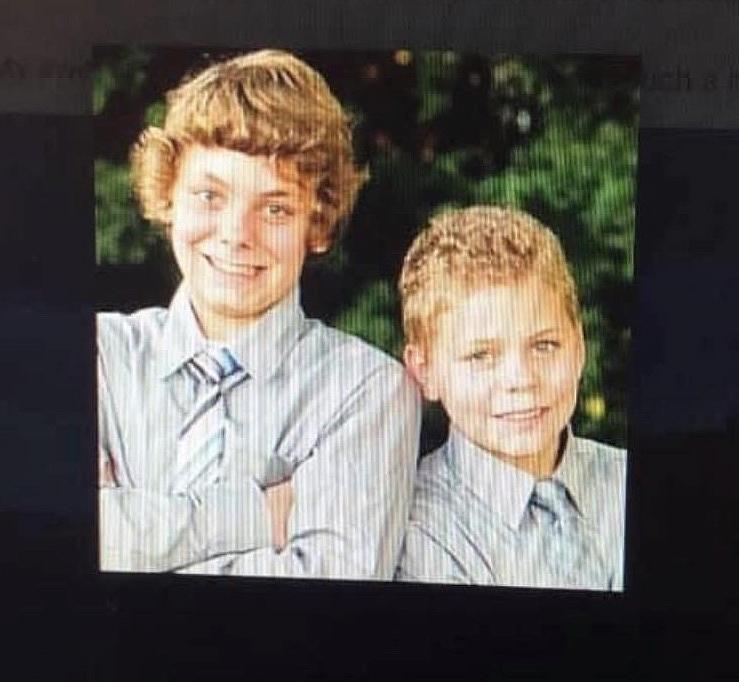

Jaydon Westermen (right) and his younger brother, who is now in prison after spending time in a PRTF. His brother, who Westermen requested not be named, did not receive the help he needed inside the mental health facility

Photo credit: Jaydon Westermen

Several weeks after checking her 11-year-old daughter into a psychiatric residential treatment facility in Arkansas, Katie James raced back to the state from her rural home in Montana after learning from her daughter there had been a riot inside Perimeter Behavioral of the Ozarks in Springdale.

“Big stuff went down,” James said her daughter recounted. “The fire department came, police came, girls started running and tried to escape. One made it all the way to the fence. Some were escorted off in handcuffs.”

Within about 72 hours of the incidents their daughter described, the James’ decided they wanted their child out of Perimeter Behavioral of the Ozarks — and out fast. The chaos ensued when a resident broke the sprinkler system, setting off a fire alarm. What followed was a confusing string of events involving one child stabbing herself in a stitched wound with a piece of metal. Another child “obtained a shank from another resident and used it to injure two RNs (registered nurses),” according to reports.

Another child assaulted police officers. At least three were arrested. Two ended up in the hospital. “I knew at that moment my daughter’s safety was worth anything,” James, who rushed to back to Arkansas from Montana to get her daughter, told me. “At what point is her being there more damaging than helpful?”

Arkansas is home to more psychiatric residential treatment facilities, or PRTFs, than almost any other state in the country. There are 13 in Arkansas, ranking it among the top 10 in the U.S., according to data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. For years, if not decades, the facilities have had ongoing, and sometimes extremely troubling, problems inside.

Children have been sexually assaulted by staff members. There have been assaults, sometimes so severe that kids have ended up in hospitals with broken bones. There are riots. Numerous elopements. And the ongoing use of draconian treatments, such as chemical restraints and solitary confinement.

Those charged with oversight, including the Arkansas Department of Human Services and Disability Rights Arkansas, have told me that regulating the industry is an ongoing challenge. There are not enough resources, for one. A governor-appointed oversight board rarely issues sanctions, and when they do, the punitive actions are so slight that often nothing of substance changes inside facilities that, instead of helping traumatized children, sometimes traumatize them more.

Nationally, the so-called troubled teen industry has been under increasing scrutiny, with journalists and researchers inquiring whether various types of residential treatment programs do more harm than good. Despite a growing spotlight on the sector, problems remain rife in rural states, like Arkansas.

It seems like all stakeholders feel helpless with trying to find better solutions. But the parents and children who are at the heart of a system that is broken, if not on the verge of collapse, continue to face victimization as they desperately seek help, yet often have nowhere to turn during times of crisis, except to facilities like PRTFs.

I have been researching PRTFs in Arkansas for a couple of years as part of an ongoing investigation into mental health care into poor, rural states, like Arkansas. What I have learned is that the PRTF industry in Arkansas has proliferated likely because the state has more relaxed regulations compared to other states. There are also few other mental health resources, particularly in rural areas, where many of these facilities are located.

This multi-part project for the 2023 Data Fellowship aims to offer solutions to state regulators and other stakeholders that might not only more effectively regulate PRTFs but also provide models for other mental health treatment infrastructure that would offer parents better solutions for children in need.

Arkansas DHS and Disability Rights Arkansas, a federally mandated PRTF watchdog group, have collected hundreds, if not thousands, of reports that describe what happens inside PRTFs. Such data has never been organized in any cohesive, chronological manner, which would allow regulators to track what happens in PRTFs over time, potentially allowing for greater insight into regulatory weaknesses and paths for solutions.

I’ve had the privilege of interviewing families as well as adults who once were placed in such facilities. Jaydon Westerman, for example, told me how his younger brother’s mental health drastically deteriorated during his months-long stay in a PRTF. His brother aged out of the system, ended up on the streets and is now in prison.

The desperate need for help and for more effective mental health treatment options for children is the driving force behind this project. I hope that I can provide families with more resources. I hope that the series will inspire regulators, and lawmakers, to take meaningful steps to fix a system that, in most cases, is simply no longer working.