In efforts to curtail rising C-section rates, data prove key

California, just like the country at large, has a growing problem with cesarean or C-section births.

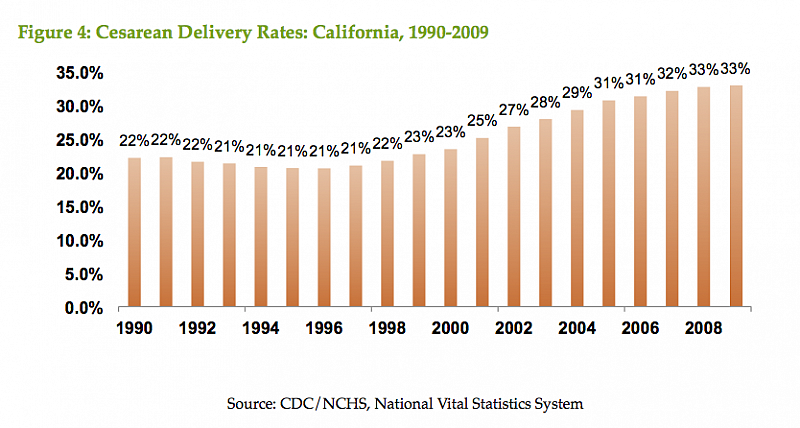

Over just a 10-year period, C-sections rose by 50 percent in the state, from 22 percent of all births in 1998 to 33 percent by 2008. The rise comes as more women are having first-birth C-sections, and fewer women are having vaginal births after a previous cesarean. According to obstetric experts, the trend is worrying.

“This has been without any demonstrable increase in baby safety or improved baby outcomes,” said Dr. Elliott Main, an obstetrician-gynecologist who directs the California Maternal Quality Care Collaboration (CMQCC). Main, who also teaches at Stanford and UC San Francisco, spoke at an October briefing on improving maternity care hosted by the California HealthCare Foundation.

While some C-sections are medically justified, many are not. And that’s a concern, since the procedure carries both added costs and risks, as a widely-cited report Dr. Main co-authored explains:

Higher cesarean delivery rates have brought higher economic costs and greater health complications for mother and baby, with little demonstrable benefit for the large majority of cases.

For babies, health problems include greater likelihood of respiratory complications. A 2009 study found that babies born via C-section had significantly higher rates of respiratory problems, neonatal intensive care admissions and longer hospital stays. For mothers, C-sections carry risks of hemorrhaging and infection. The risks are low for a first cesarean, but increase dramatically for subsequent C-sections.

But the problem goes beyond steadily rising C-section rates. There’s also the problem of wide variation between hospitals. In California, some hospitals deliver as few as 10 percent of babies by C-section, while at the other end of the spectrum, 75 percent are born via cesarean. While the national target rate is about 24 percent, only about a third of California hospitals have rates that come in under that figure, according to Main.

As the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care has long illustrated, “excess” medical interventions not only contribute to the runaway health spending but also often fail to deliver any better health outcomes. Reimbursement rates for C-sections average about 60 percent higher than vaginal births. One analysis estimated that the rise in the C-section rate from 2000 to 2011 resulted in additional costs of $240 million for the state’s public and private payers.

Bringing down C-section rates at hospitals that exceed the target proportion hasn’t been easy. As the CMQCC report noted, editorials in medical journals and childbirth advocates have pushed unsuccessfully to reverse the trend for decades. Dr. Main acknowledged the challenge:

It’s not easy to change medical practice. It’s not easy to change our habits, either personally or professionally. We do need pressures to break the status quo, to provide reasons to change. But in this process there are lots of opportunities to be collaborative.

(In a column earlier this year, The New York Times’ Tina Rosenberg outlined problems with the current payment structure as well. Rosenberg argued that private practice ob-gyns have financial incentives to deliver their patients’ babies themselves, and so schedule C-sections to fit their schedules.)

While there are no signs yet that the overall trend line has reversed, there are glimmers of progress. And good data is a critical first step. With that in mind, Main’s organization has been diligently amassing birth certificate records and other data from California hospitals. The goal is to use the resulting data points and metrics to jumpstart interventions to lower cesarean rates at hospitals that are well above the average.

That data-driven approach has already resulted in an encouraging pilot project at one Southern California hospital that was facing mounting pushback over its C-section rate, said Dr. Main at last month’s briefing: “One of the drivers at this hospital to change was that big employers were coming to them and saying, ‘Your C-section rate is pretty high. You know, we may not continue to contract with you.’”

The medical center launched a pilot project in January 2014 designed to lower attempt its C-section rate, which at the time was 32 percent. By May of that year, a mere five months later, the rate had dropped to 23.4 percent. (The hospital and medical group in question have so far declined to be identified.)

Dr. Sandra R. Hernández, CEO of the California HealthCare Foundation, praised the pilot program’s approach in a blog post. She wrote:

This is a great example of using data to drive quality improvement, in real time, with benefit to mothers and families alike. Imagine what could be accomplished if the more than 250 California hospitals that deliver babies adopted a similar program?

Larger efforts are underway as well.

The state is currently awaiting federal approval for its California State Innovation Model Maternity Care Initiative. The grant-funded program calls for steps to lower the number of early elective deliveries (births between 36 and 39 weeks without a medical cause) and C-sections statewide. The effort would also provide incentives to hospitals to allow some patients to give birth vaginally after C-section (V.B.A.C.) About half of the state’s hospitals currently don’t give Medicaid patients the option, despite a recommendation to do so from the National Institutes of Health.

“Change can happen when the pressure points are aligned,” Dr. Main told his audience last month. “We’re still working on making this a public agenda.”

(Graphic above from CQMCC)

Photo by George Ruiz via Flickr.